Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

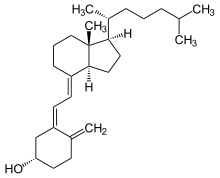

Cholecalciferol

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌkoʊləkælˈsɪfərɒl/ |

| Other names | vitamin D3 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Professional Drug Facts |

| License data | |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intramuscular |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.612 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C27H44O |

| Molar mass | 384.648 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 83 to 86 °C (181 to 187 °F) |

| Boiling point | 496.4 °C (925.5 °F) |

| Solubility in water | Practically insoluble in water, freely soluble in ethanol, methanol and some other organic solvents. Slightly soluble in vegetable oils. |

| |

| |

Cholecalciferol, also known as vitamin D3 or colecalciferol, is a type of vitamin D that is produced by the skin when exposed to UVB light; it is found in certain foods and can be taken as a dietary supplement.[3]

Cholecalciferol is synthesised in the skin following sunlight exposure.[4] It is then converted in the liver to calcifediol (25-hydroxycholecalciferol D), which is further converted in the kidney to calcitriol (1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol D).[4] One of calcitriol’s most important functions is to promote calcium uptake by the intestines.[5] Cholecalciferol is present in food such as fatty fish, beef liver, eggs, and cheese.[6][7] In some countries, cholecalciferol is also added to products like plants, cow milk, fruit juice, yogurt, and margarine.[6][7]

Cholecalciferol can be taken orally as a dietary supplement to prevent vitamin D deficiency or as a medication to treat associated diseases, including rickets.[8][9] It is also used in the management of familial hypophosphatemia, hypoparathyroidism that is causing low blood calcium, and Fanconi syndrome.[9][10] Vitamin-D supplements may not be effective in people with severe kidney disease.[11][10] Excessive doses in humans can result in vomiting, constipation, muscle weakness, and confusion.[5] Other risks include kidney stones.[11] Doses greater than 40000 IU (1000 μg) per day are generally required before high blood calcium occurs.[12] Normal doses, 800–2000 IU per day, are safe in pregnancy.[5]

Cholecalciferol was first described in 1936.[13] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[14] In 2022, it was the 62nd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 10 million prescriptions.[15][16] Cholecalciferol is available as a generic medication.[10][17][18]

- ^ "Health product highlights 2021: Annexes of products approved in 2021". Health Canada. 3 August 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ "Regulatory Decision Summary for Vitamin D3 Oral Solution". Health Canada. 5 February 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ Coulston AM, Boushey C, Ferruzzi M (2013). Nutrition in the Prevention and Treatment of Disease. Academic Press. p. 818. ISBN 9780123918840. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- ^ a b Norman AW (August 2008). "From vitamin D to hormone D: fundamentals of the vitamin D endocrine system essential for good health". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 88 (2): 491S – 499S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/88.2.491S. PMID 18689389.

- ^ a b c "Cholecalciferol (Professional Patient Advice) - Drugs.com". www.drugs.com. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- ^ a b "Office of Dietary Supplements - Vitamin D". ods.od.nih.gov. 11 February 2016. Archived from the original on 31 December 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- ^ a b Ross AC, Taylor CL, Yaktine AL, Del Valle HB, et al. (Institute of Medicine (US); Committee to Review Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin D and Calcium) (2011). Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D (PDF). National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/13050. ISBN 978-0-309-16394-1. PMID 21796828. S2CID 58721779.

- ^ British national formulary : BNF 69 (69 ed.). British Medical Association. 2015. pp. 703–704. ISBN 9780857111562.

- ^ a b World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 9789241547659.

- ^ a b c Hamilton R (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 231. ISBN 9781284057560.

- ^ a b "Aviticol 1 000 IU Capsules - Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) - (eMC)". www.medicines.org.uk. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- ^ Vieth R (May 1999). "Vitamin D supplementation, 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations, and safety" (PDF). The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 69 (5): 842–56. doi:10.1093/ajcn/69.5.842. PMID 10232622.

- ^ Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 451. ISBN 978-3-527-60749-5. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2022". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 30 August 2024. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "Cholecalciferol Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013 - 2022". ClinCalc. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

merckvet2014was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Rizor SE, Arjo WM, Bulkin S, Nolte DL. Efficacy of Cholecalciferol Baits for Pocket Gopher Control and Possible Effects on Non-Target Rodents in Pacific Northwest Forests. Vertebrate Pest Conference (2006). USDA. Archived from the original on 14 September 2012. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

0.15% cholecalciferol bait appears to have application for pocket gopher control.' Cholecalciferol can be a single high-dose toxicant or a cumulative multiple low-dose toxicant.

Previous Page Next Page