Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

Endosymbiont

An endosymbiont or endobiont[1] is an organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism. Typically the two organisms are in a mutualistic relationship. Examples are nitrogen-fixing bacteria (called rhizobia), which live in the root nodules of legumes, single-cell algae inside reef-building corals, and bacterial endosymbionts that provide essential nutrients to insects.[2][3]

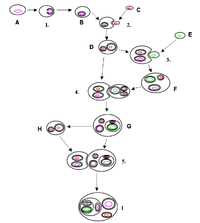

Endosymbiosis played key roles in the development of eukaryotes and plants. Roughly 2.2 billion years ago an archaeon absorbed a bacterium through phagocytosis, that eventually became the mitochondria that provide energy to almost all living eukaryotic cells. Approximately 1 billion years ago, some of those cells absorbed cyanobacteria that eventually became chloroplasts, organelles that produce energy from sunlight.[4] Approximately 100 million years ago, a lineage of amoeba in the genus Paulinella independently engulfed a cyanobacteria that evolved to be functionally synonymous with traditional chloroplasts, called chromatophores.[5]

Some 100 million years ago, UCYN-A, a nitrogen-fixing bacterium, became an endosymbiont of the marine alga Braarudosphaera bigelowii, eventually evolving into a nitroplast, which fixes nitrogen.[6] Similarly, diatoms in the family Rhopalodiaceae have cyanobacterial endosymbionts, called spheroid bodies or diazoplasts, which have been proposed to be in the early stages of organelle evolution.[7][8]

Symbionts are either obligate (require their host to survive) or facultative (can survive independently).[9] The most common examples of obligate endosymbiosis are mitochondria and chloroplasts; however, they do not reproduce via mitosis in tandem with their host cells. Instead, they replicate via binary fission, a replication process uncoupled from the host cells in which they reside.[10][11] Some human parasites, e.g. Wuchereria bancrofti and Mansonella perstans, thrive in their intermediate insect hosts because of an obligate endosymbiosis with Wolbachia spp.[12] They can both be eliminated by treatments that target their bacterial host.[13]

- ^ Margulis L, Chapman MJ (2009). Kingdoms & domains an illustrated guide to the phyla of life on Earth (4th ed.). Amsterdam: Academic Press/Elsevier. p. 493. ISBN 978-0-08-092014-6.

- ^ Mergaert P (April 2018). "Role of antimicrobial peptides in controlling symbiotic bacterial populations". Natural Product Reports. 35 (4): 336–356. doi:10.1039/c7np00056a. PMID 29393944.

- ^ Little AF, van Oppen MJ, Willis BL (June 2004). "Flexibility in algal endosymbioses shapes growth in reef corals". Science. 304 (5676): 1492–1494. Bibcode:2004Sci...304.1491L. doi:10.1126/science.1095733. PMID 15178799. S2CID 10050417.

- ^ Baisas, Laura (18 April 2024). "For the first time in one billion years, two lifeforms truly merged into one organism". Popular Science. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ Macorano, Luis; Nowack, Eva C.M. (13 September 2021). "Paulinella chromatophora". Current Biology. 31 (17): R1024 – R1026. Bibcode:2021CBio...31R1024M. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2021.07.028. ISSN 0960-9822.

- ^ Wong, Carissa (11 April 2024). "Scientists discover first algae that can fix nitrogen — thanks to a tiny cell structure". Nature. 628 (8009). Nature.com: 702. Bibcode:2024Natur.628..702W. doi:10.1038/d41586-024-01046-z. PMID 38605201. Archived from the original on 14 April 2024. Retrieved 16 April 2024.

- ^ Nakayama, T.; Inagaki, Y. (2017). "Genomic divergence within non-photosynthetic cyanobacterial endosymbionts in rhopalodiacean diatoms". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 13075. Bibcode:2017NatSR...713075N. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-13578-8. PMC 5638926. PMID 29026213.

- ^ Schvarcz, Christopher R.; Wilson, Samuel T.; Caffin, Mathieu; Stancheva, Rosalina; Li, Qian; Turk-Kubo, Kendra A.; White, Angelicque E.; Karl, David M.; Zehr, Jonathan P.; Steward, Grieg F. (10 February 2022). "Overlooked and widespread pennate diatom-diazotroph symbioses in the sea". Nature Communications. 13 (1): 799. Bibcode:2022NatCo..13..799S. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-28065-6. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 8831587. PMID 35145076.

- ^ Bright, Monika; Bulgheresi, Silvia (March 2010). "A complex journey: transmission of microbial symbionts". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 8 (3): 218–230. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2262. ISSN 1740-1534. PMC 2967712. PMID 20157340.

- ^ "Mitochondria, Cell Energy, ATP Synthase | Learn Science at Scitable". www.nature.com. Retrieved 31 December 2024.

- ^ Rose, Ray J (20 September 2019). "Sustaining Life: Maintaining Chloroplasts and Mitochondria and their Genomes in Plants". National Library of Medicine: National Center for Biotechnology Information. Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. PMID 31543711. Retrieved 31 December 2024.

- ^ Slatko, Barton E.; Taylor, Mark J.; Foster, Jeremy M. (1 July 2010). "The Wolbachia endosymbiont as an anti-filarial nematode target". Symbiosis. 51 (1): 55–65. Bibcode:2010Symbi..51...55S. doi:10.1007/s13199-010-0067-1. ISSN 1878-7665. PMC 2918796. PMID 20730111.

- ^ Warrell D, Cox TM, Firth J, Török E (11 October 2012). Oxford Textbook of Medicine: Infection. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-965213-6.

Previous Page Next Page