Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

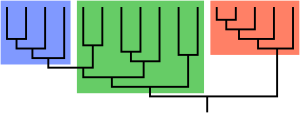

Polyphyly

A polyphyletic group is an assemblage that includes organisms with mixed evolutionary origin but does not include their most recent common ancestor.[1] The term is often applied to groups that share similar features known as homoplasies, which are explained as a result of convergent evolution. The arrangement of the members of a polyphyletic group is called a polyphyly /ˈpɒlɪˌfaɪli/.[2] It is contrasted with monophyly and paraphyly.

For example, the biological characteristic of warm-bloodedness evolved separately in the ancestors of mammals and the ancestors of birds; "warm-blooded animals" is therefore a polyphyletic grouping.[3] Other examples of polyphyletic groups are algae, C4 photosynthetic plants,[4] and edentates.[5]

Many taxonomists aim to avoid homoplasies in grouping taxa together, with a goal to identify and eliminate groups that are found to be polyphyletic. This is often the stimulus for major revisions of the classification schemes. Researchers concerned more with ecology than with systematics may take polyphyletic groups as legitimate subject matter; the similarities in activity within the fungus group Alternaria, for example, can lead researchers to regard the group as a valid genus while acknowledging its polyphyly.[6] In recent research, the concepts of monophyly, paraphyly, and polyphyly have been used in deducing key genes for barcoding of diverse groups of species.[7]

- ^ Urry, Lisa A. (2016). Campbell Biology (11th ed.). Pearson. p. 558. ISBN 978-0-134-09341-3.

- ^ "polyphyly". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. Retrieved 28 December 2021. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.). [Source for pronunciation.]

- ^ Archibald, J. David (2014-07-15). Aristotle's Ladder, Darwin's Tree: The Evolution of Visual Metaphors for Biological Order. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231164122.

- ^ Sage, Rowan F. (2004-02-01). "The evolution of C4 photosynthesis". New Phytologist. 161 (2): 341–370. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.00974.x. ISSN 1469-8137. PMID 33873498.

- ^ Delsuc, Frédéric; Douzery, Emmanuel J. P. (2008). "Recent advances and future prospects in xenarthran molecular phylogenetics". In Vizcaíno, Sergio F.; Loughry, W. J. (eds.). The biology of the Xenarthra. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. pp. 11–23. ISBN 9780813031651. OCLC 741613153.

- ^ Aschehoug, Erik T.; Metlen, Kerry L.; Callaway, Ragan M.; Newcombe, George (2012). "Fungal endophytes directly increase the competitive effects of an invasive forb". Ecology. 93 (1): 3–8. doi:10.1890/11-1347.1. PMID 22486080.

- ^ Parhi J., Tripathy P.S., Priyadarshi, H., Mandal S.C., Pandey P.K. (2019). "Diagnosis of mitogenome for robust phylogeny: A case of Cypriniformes fish group". Gene. 713: 143967. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2019.143967. PMID 31279710. S2CID 195828782.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Previous Page Next Page