Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

Portal:Viruses

The Viruses Portal

Welcome!

Viruses are small infectious agents that can replicate only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all forms of life, including animals, plants, fungi, bacteria and archaea. They are found in almost every ecosystem on Earth and are the most abundant type of biological entity, with millions of different types, although only about 6,000 viruses have been described in detail. Some viruses cause disease in humans, and others are responsible for economically important diseases of livestock and crops.

Virus particles (known as virions) consist of genetic material, which can be either DNA or RNA, wrapped in a protein coat called the capsid; some viruses also have an outer lipid envelope. The capsid can take simple helical or icosahedral forms, or more complex structures. The average virus is about 1/100 the size of the average bacterium, and most are too small to be seen directly with an optical microscope.

The origins of viruses are unclear: some may have evolved from plasmids, others from bacteria. Viruses are sometimes considered to be a life form, because they carry genetic material, reproduce and evolve through natural selection. However they lack key characteristics (such as cell structure) that are generally considered necessary to count as life. Because they possess some but not all such qualities, viruses have been described as "organisms at the edge of life".

Selected disease

Foot-and-mouth disease or FMD is an economically important disease of even-toed ungulates (cloven-hoofed animals) and some other mammals caused by the FMD virus, a picornavirus. Hosts include cattle, water buffalo, sheep, goats, pigs, antelope, deer and bison; human infection is extremely rare. After a 1–12-day incubation, animals develop high fever, and then blisters inside the mouth (pictured) and on the hooves, which can rupture and cause lameness. Weight loss and reduction in milk production are other possible long-term consequences. Mortality in adult animals is low (2–5%). The virus is highly infectious, with transmission occurring via direct contact, aerosols, semen, consumption of infected food scraps or feed supplements, and via inanimate objects including fodder, farming equipment, vehicles, standing water, and the clothes and skin of humans. Some infected ruminants can transmit infection as asymptomatic carriers.

Friedrich Loeffler showed the disease to be viral in 1897. FMD was widely distributed in 1945. By 2014, North America, Australia, New Zealand, much of Europe, and some South American countries were free of the disease. Major outbreaks include one in the UK in 2001 that cost an estimated £8 billion. The virus is highly variable, with seven serotypes. A vaccine is available, but protection is temporary and strain specific. Other control methods include monitoring programmes, trade restrictions, quarantine, and the slaughter of infected and healthy at-risk animals.

Selected image

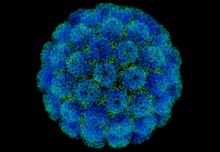

The common cold is the most frequent infectious disease. Despite the advice to "consult your physician" no antiviral treatment has been approved, and colds are only rarely associated with serious complications.

Credit: Federal Art Project (1937)

In the news

26 February: In the ongoing pandemic of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), more than 110 million confirmed cases, including 2.5 million deaths, have been documented globally since the outbreak began in December 2019. WHO

18 February: Seven asymptomatic cases of avian influenza A subtype H5N8, the first documented H5N8 cases in humans, are reported in Astrakhan Oblast, Russia, after more than 100,0000 hens died on a poultry farm in December. WHO

14 February: Seven cases of Ebola virus disease are reported in Gouécké, south-east Guinea. WHO

7 February: A case of Ebola virus disease is detected in North Kivu Province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. WHO

4 February: An outbreak of Rift Valley fever is ongoing in Kenya, with 32 human cases, including 11 deaths, since the outbreak started in November. WHO

21 November: The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) gives emergency-use authorisation to casirivimab/imdevimab, a combination monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapy for non-hospitalised people twelve years and over with mild-to-moderate COVID-19, after granting emergency-use authorisation to the single mAb bamlanivimab earlier in the month. FDA 1, 2

18 November: The outbreak of Ebola virus disease in Équateur Province, Democratic Republic of the Congo, which started in June, has been declared over; a total of 130 cases were recorded, with 55 deaths. UN

Selected article

RNA interference is a type of gene silencing that forms an important part of the immune response against viruses and other foreign genetic material in plants and many other eukaryotes. A cell enzyme called Dicer (pictured) cleaves double-stranded RNA molecules found in the cell cytoplasm – such as the genome of an RNA virus or its replication intermediates – into short fragments termed small interfering RNAs (siRNAs). These are separated into single strands and integrated into a large multi-protein RNA-induced silencing complex, where they recognise their complementary messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules and target them for destruction. This prevents the mRNAs acting as a template for translation into proteins, and so inhibits, or silences, the expression of viral genes.

RNA interference allows the entire plant to respond to a virus after a localised encounter, as the siRNAs can transfer between cells via plasmodesmata. The protective effect can be transferred between plants by grafting. Many plant viruses have evolved elaborate mechanisms to suppress this response. RNA interference evolved early in eukaryotes, and the system is widespread. It is important in innate immunity towards viruses in some insects, but relatively little is known about its role in mammals. Research is ongoing into the application of RNA interference to antiviral treatments.

Selected outbreak

The West African Ebola epidemic was the most widespread outbreak of the disease to date. Beginning in Meliandou in southern Guinea in December 2013, it spread to adjacent Liberia and Sierra Leone, affecting the cities of Conakry and Monrovia, with minor outbreaks in Mali and Nigeria. Cases reached a peak in October 2014 and the epidemic was under control by late 2015, although occasional cases continued to occur into April 2016. Ring vaccination with the then-experimental vaccine rVSV-ZEBOV was trialled in Guinea.

More than 28,000 suspected cases were reported with more than 11,000 deaths; the case fatality rate was around 40% overall and around 58% in hospitalised patients. Early in the epidemic nearly 10% of the dead were healthcare workers. The outbreak left about 17,000 survivors, many of whom reported long-lasting post-recovery symptoms. Extreme poverty, dysfunctional healthcare systems, distrust of government after years of armed conflict, local burial customs of washing the body, the unprecedented spread of Ebola to densely populated cities, and the delay in response of several months all contributed to the failure to control the epidemic.

Selected quotation

| “ | ...the variety of genes on the planet in viruses exceeds, or is likely to exceed, that in all of the rest of life combined. | ” |

Recommended articles

Viruses & Subviral agents: bat virome • elephant endotheliotropic herpesvirus • HIV • introduction to viruses![]() • Playa de Oro virus • poliovirus • prion • rotavirus

• Playa de Oro virus • poliovirus • prion • rotavirus![]() • virus

• virus![]()

Diseases: colony collapse disorder • common cold • croup • dengue fever![]() • gastroenteritis • Guillain–Barré syndrome • hepatitis B • hepatitis C • hepatitis E • herpes simplex • HIV/AIDS • influenza

• gastroenteritis • Guillain–Barré syndrome • hepatitis B • hepatitis C • hepatitis E • herpes simplex • HIV/AIDS • influenza![]() • meningitis

• meningitis![]() • myxomatosis • polio

• myxomatosis • polio![]() • pneumonia • shingles • smallpox

• pneumonia • shingles • smallpox

Epidemiology & Interventions: 2007 Bernard Matthews H5N1 outbreak • Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations • Disease X • 2009 flu pandemic • HIV/AIDS in Malawi • polio vaccine • Spanish flu • West African Ebola virus epidemic

Virus–Host interactions: antibody • host • immune system![]() • parasitism • RNA interference

• parasitism • RNA interference![]()

Methodology: metagenomics

Social & Media: And the Band Played On • Contagion • "Flu Season" • Frank's Cock![]() • Race Against Time: Searching for Hope in AIDS-Ravaged Africa

• Race Against Time: Searching for Hope in AIDS-Ravaged Africa![]() • social history of viruses

• social history of viruses![]() • "Steve Burdick" • "The Time Is Now" • "What Lies Below"

• "Steve Burdick" • "The Time Is Now" • "What Lies Below"

People: Brownie Mary • Macfarlane Burnet![]() • Bobbi Campbell • Aniru Conteh • people with hepatitis C

• Bobbi Campbell • Aniru Conteh • people with hepatitis C![]() • HIV-positive people

• HIV-positive people![]() • Bette Korber • Henrietta Lacks • Linda Laubenstein • Barbara McClintock

• Bette Korber • Henrietta Lacks • Linda Laubenstein • Barbara McClintock![]() • poliomyelitis survivors

• poliomyelitis survivors![]() • Joseph Sonnabend • Eli Todd • Ryan White

• Joseph Sonnabend • Eli Todd • Ryan White![]()

Selected virus

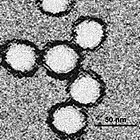

West Nile virus (WNV) is a flavivirus, an RNA virus in the Flaviviridae family. The enveloped virion is 45–50 nm in diameter and contains a single-stranded, positive-sense RNA genome of around 11,000 nucleotides, encoding ten proteins. The main natural hosts are birds (the reservoir) and several species of Culex mosquito (the vector). WNV can also infect humans and some other mammals, including horses, dogs and cats, as well as some reptiles. Transmission to humans is generally by bite of the female mosquito. Mammals form a dead end for the virus, as it cannot replicate sufficiently efficiently in them to complete the cycle back to the mosquito.

First identified in Uganda in 1937, WNV was at first mainly associated with disease in horses, with only sporadic cases of human disease until the 1990s. The virus is now endemic in Africa, west and central Asia, Oceania, the Middle East, Europe and North America. A fifth of humans infected experience West Nile fever, a flu-like disease. In less than 1% of those infected, the virus invades the central nervous system, causing encephalitis, meningitis or flaccid paralysis. No specific antiviral treatment has been licensed and only a veterinary vaccine is available. Mosquito control is the main preventive measure.

Did you know?

- ...that besides feeding on soybeans and transmitting viruses to them, a soybean aphid (pictured) can also injure the plant by interfering with its photosynthetic pathways?

- ...that transmission of COVID-19 is known to occur through respiratory droplets, contaminated surfaces, kissing, and aerosol-generating medical procedures?

- ...that medical researcher Shuping Wang may have saved tens of thousands of lives by defying authorities and exposing an HIV/AIDS scandal in China?

- ...that the Global Certification Commission has certified the eradication of wild poliovirus in five of the six WHO regions, with the exception of the Eastern Mediterranean Region?

- ...that in 1953, American scientist Winston Price isolated the first rhinovirus, the most prevalent cause of the common cold?

Selected biography

Peter Piot (born 17 February 1949) is a Belgian virologist and public health specialist, known for his work on Ebola virus and HIV.

During the first outbreak of Ebola in Yambuku, Zaire in 1976, Piot was one of a team that discovered the filovirus in a blood sample. He and his colleagues travelled to Zaire to help to control the outbreak, and showed that the virus is transmitted via blood and during preparation of bodies for burial. He advised WHO during the West African Ebola epidemic of 2014–16.

In the 1980s, Piot participated in collaborative projects in Burundi, Côte d'Ivoire, Kenya, Tanzania and Zaire, including Project SIDA in Kinshasa, the first international project on AIDS in Africa, which provided the foundations for understanding HIV infection in that continent. He was the founding director of UNAIDS, and has served as president of the International AIDS Society and assistant director of the WHO Global HIV/AIDS Programme. As of 2020, he directs the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

In this month

1 January 1934: Discovery of mumps virus by Claud Johnson and Ernest Goodpasture

1 January 1942: Publication of George Hirst's paper on the haemagglutination assay

1 January 1967: Start of WHO intensified eradication campaign for smallpox (vaccination kit pictured)

3 January 1938: Foundation of March of Dimes, to raise money for polio

6 January 2011: Andrew Wakefield's paper linking the MMR vaccine with autism described as "fraudulent" by the BMJ

25 January 1988: Foundation of the International AIDS Society

29 January 1981: Influenza haemagglutinin structure published by Ian Wilson, John Skehel and Don Wiley, the first viral membrane protein whose structure was solved

Selected intervention

| “ | the most damaging medical hoax of the last 100 years —Dennis Flaherty, 2011 |

” |

The MMR vaccine and autism fraud refers to the false claim that the combined vaccine for measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) might be associated with colitis and autism spectrum disorders. Multiple large epidemiological studies have since found no link between the vaccine and autism. The notion originated in a fraudulent research paper by Andrew Wakefield and co-authors, published in the prestigious medical journal The Lancet in 1998. Sunday Times journalist Brian Deer's investigations revealed that Wakefield had manipulated evidence and had multiple undeclared conflicts of interest. The paper was retracted in 2010, when the Lancet's editor-in-chief Richard Horton characterised it as "utterly false". Wakefield was found guilty of serious professional misconduct by the General Medical Council, and struck off the UK's Medical Register. The claims in Wakefield's article were widely reported in the press, resulting in a sharp drop in vaccination uptake in the UK and Ireland. A greatly increased incidence of measles and mumps followed, leading to deaths and serious permanent injuries.

Subcategories

Subcategories of virology:

Topics

Things to do

- Comment on what you like and dislike about this portal

- Join the Viruses WikiProject

- Tag articles on viruses and virology with the project banner by adding {{WikiProject Viruses}} to the talk page

- Assess unassessed articles against the project standards

- Create requested pages: red-linked viruses | red-linked virus genera

- Expand a virus stub into a full article, adding images, citations, references and taxoboxes, following the project guidelines

- Create a new article (or expand an old one 5-fold) and nominate it for the main page Did You Know? section

- Improve a B-class article and nominate it for Good Article

or Featured Article

or Featured Article status

status - Suggest articles, pictures, interesting facts, events and news to be featured here on the portal

WikiProjects & Portals

WikiProject Viruses

Related WikiProjects

WikiProject Viruses

Related WikiProjects

Medicine • Microbiology • Molecular & Cellular Biology • Veterinary Medicine

Related PortalsAssociated Wikimedia

The following Wikimedia Foundation sister projects provide more on this subject:

-

Commons

Free media repository -

Wikibooks

Free textbooks and manuals -

Wikidata

Free knowledge base -

Wikinews

Free-content news -

Wikiquote

Collection of quotations -

Wikisource

Free-content library -

Wikispecies

Directory of species -

Wikiversity

Free learning tools -

Wiktionary

Dictionary and thesaurus

Previous Page Next Page