Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

Rigveda

| Rigveda | |

|---|---|

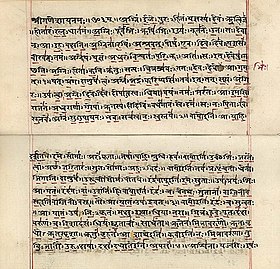

Rigveda (padapāṭha) manuscript in Devanāgarī, early 19th century. After a scribal benediction (śrīgaṇéśāyanamaḥ oṁ), the first line has the first pada, RV 1.1.1a (agniṃ iḷe puraḥ-hitaṃ yajñasya devaṃ ṛtvijaṃ). The pitch-accent is marked by underscores and vertical overscores in red. | |

| Information | |

| Religion | Historical Vedic religion Hinduism |

| Language | Vedic Sanskrit |

| Period | c. 1500–1000 BCE[note 1] (Vedic period) |

| Chapters | 10 mandalas |

| Verses | 10,552 mantras[1] |

| Part of a series on |

| Hindu scriptures and texts |

|---|

|

| Related Hindu texts |

The Rigveda or Rig Veda (Sanskrit: ऋग्वेद, IAST: ṛgveda, from ऋच्, "praise"[2] and वेद, "knowledge") is an ancient Indian collection of Vedic Sanskrit hymns (sūktas). It is one of the four sacred canonical Hindu texts (śruti) known as the Vedas.[3][4] Only one Shakha of the many survive today, namely the Śakalya Shakha. Much of the contents contained in the remaining Shakhas are now lost or are not available in the public forum.[5]

The Rigveda is the oldest known Vedic Sanskrit text.[6] Its early layers are among the oldest extant texts in any Indo-European language.[7][note 2] Most scholars believe that the sounds and texts of the Rigveda have been orally transmitted with precision since the 2nd millennium BCE,[9][10][11] through methods of memorisation of exceptional complexity, rigour and fidelity,[12][13][14] though the dates are not confirmed and remain contentious till concrete evidence surfaces.[15] Philological and linguistic evidence indicates that the bulk of the Rigveda Samhita was composed in the northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent (see Rigvedic rivers), most likely between c. 1500 and 1000 BCE,[16][17][18] although a wider approximation of c. 1900–1200 BCE has also been given.[19][20][note 1]

The text is layered, consisting of the Samhita, Brahmanas, Aranyakas and Upanishads.[note 3] The Rigveda Samhita is the core text and is a collection of 10 books (maṇḍalas) with 1,028 hymns (sūktas) in about 10,600 verses (called ṛc, eponymous of the name Rigveda). In the eight books – Books 2 through 9 – that were composed the earliest, the hymns predominantly discuss cosmology, rites required to earn the favour of the gods,[21] as well as praise them.[22][23] The more recent books (Books 1 and 10) in part also deal with philosophical or speculative questions,[23] virtues such as dāna (charity) in society,[24] questions about the origin of the universe and the nature of the divine,[25][26] and other metaphysical issues in their hymns.[27]

The hymns of the Rigveda are notably similar to the most archaic poems of the Iranian and Greek language families, the Gathas of old Avestan and Iliad of Homer.[28] The Rigveda's preserved archaic syntax and morphology are of vital importance in the reconstruction of the common ancestor language Proto-Indo-European.[28] Some of its verses continue to be recited during Hindu prayer and celebration of rites of passage (such as weddings), making it probably the world's oldest religious text in continued use.[29][30]

Cite error: There are <ref group=note> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=note}} template (see the help page).

- ^ "Construction of the Vedas". VedicGranth.Org. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ Derived from the root ṛc "to praise", cf. Dhātupātha 28.19. Monier-Williams translates Rigveda as "a Veda of Praise or Hymn-Veda".

- ^ Witzel 1997, pp. 259–264.

- ^ Antonio de Nicholas (2003), Meditations Through the Rig Veda: Four-Dimensional Man, New York: Authors Choice Press, ISBN 978-0-595-26925-9, p. 273

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:0was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Stephanie W. Jamison (tr.) & Joel P. Brereton (tr.) 2014, p. 3.

- ^ Bryant, Edwin F. (2015). The Yoga Sutras of Patañjali: A New Edition, Translation, and Commentary. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. pp. 565–566. ISBN 978-1-4299-9598-6. Archived from the original on 7 September 2023. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- ^ Polomé, Edgar (2010). Per Sture Ureland (ed.). Entstehung von Sprachen und Völkern: glotto- und ethnogenetische Aspekte europäischer Sprachen. Walter de Gruyter. p. 51. ISBN 978-3-11-163373-2. Archived from the original on 7 September 2023. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- ^ Wood 2007.

- ^ Hexam 2011, p. chapter 8.

- ^ Dwyer 2013.

- ^ Witzel, Michael (2005). "Vedas and Upaniṣads". In Gavin Flood (ed.). The Blackwell companion to Hinduism (1st paperback ed.). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 68–71. ISBN 1-4051-3251-5.: "The Vedic texts were orally composed and transmitted, without the use of script, in an unbroken line of transmission from teacher to student that was formalized early on. This ensured an impeccable textual transmission superior to the classical texts of other cultures; it is, in fact, something like a tape-recording of ca. 1500–500 BCE. Not just the actual words, but even the long-lost musical (tonal) accent (as in old Greek or in Japanese) has been preserved up to the present"

- ^ Staal, Frits (1986). The Fidelity of Oral Tradition and the Origins of Science. Mededelingen der Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie von Wetenschappen, Amsterdam: North Holland Publishing Company.

- ^ Filliozat, Pierre-Sylvain (2004). "Ancient Sanskrit Mathematics: An Oral Tradition and a Written Literature". In Chemla, Karine; Cohen, Robert S.; Renn, Jürgen; et al. (eds.). History of Science, History of Text (Boston Series in the Philosophy of Science). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. pp. 360–375. doi:10.1007/1-4020-2321-9_7. ISBN 978-1-4020-2320-0.

- ^ Jamison & Brereton 2014, p. 5-7.

- ^ Flood 1996, p. 37.

- ^ Anthony 2007, p. 454.

- ^ Witzel 2019, p. 11: "Incidentally, the Indo-Aryan loanwords in Mitanni confirm the date of the Rig Veda for ca. 1200–1000 BCE. The Rig Veda is a late Bronze age text, thus from before 1000 BCE. However, the Mitanni words have a form of Indo-Aryan that is slightly older than that ... Clearly the Rig Veda cannot be older than ca. 1400, and taking into account a period needed for linguistic change, it may not be much older than ca. 1200 BCE."

- ^ Oberlies 1998, p. 158.

- ^ Lucas F. Johnston, Whitney Bauman (2014). Science and Religion: One Planet, Many Possibilities. Routledge. p. 179.

- ^ Bauer, Susan Wise (2007). The History of the Ancient World: From the Earliest Accounts to the Fall of Rome (1st ed.). New York: W. W. Norton. p. 265. ISBN 978-0-393-05974-8.

- ^ Werner, Karel (1994). A Popular Dictionary of Hinduism. Curzon Press. ISBN 0-7007-1049-3.

- ^ a b Stephanie W. Jamison (tr.) & Joel P. Brereton (tr.) 2014, pp. 4, 7–9.

- ^ C Chatterjee (1995), Values in the Indian Ethos: An Overview, Journal of Human Values, Vol 1, No 1, pp. 3–12;

Original text translated in English: The Rig Veda, Mandala 10, Hymn 117, Ralph T. H. Griffith (Translator); - ^ Cite error: The named reference

3translationswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Examples:

Verse 1.164.34, "What is the ultimate limit of the earth?", "What is the center of the universe?", "What is the semen of the cosmic horse?", "What is the ultimate source of human speech?"

Verse 1.164.34, "Who gave blood, soul, spirit to the earth?", "How could the unstructured universe give origin to this structured world?"

Verse 1.164.5, "Where does the sun hide in the night?", "Where do gods live?"

Verse 1.164.6, "What, where is the unborn support for the born universe?";

Verse 1.164.20 (a hymn that is widely cited in the Upanishads as the parable of the Body and the Soul): "Two birds with fair wings, inseparable companions; Have found refuge in the same sheltering tree. One incessantly eats from the fig tree; the other, not eating, just looks on.";

Rigveda Book 1, Hymn 164 Wikisource;

See translations of these verses: Stephanie W. Jamison (tr.) & Joel P. Brereton (tr.) (2014) - ^ Antonio de Nicholas (2003), Meditations Through the Rig Veda: Four-Dimensional Man, New York: Authors Choice Press, ISBN 978-0-595-26925-9, pp. 64–69;

Jan Gonda (1975), A History of Indian Literature: Veda and Upanishads, Volume 1, Part 1, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3-447-01603-2, pp. 134–135. - ^ a b Lowe, John J. (2015). Participles in Rigvedic Sanskrit: The Syntax and Semantics of Adjectival Verb Forms. Oxford University Press. pp. 2–. ISBN 978-0-19-100505-3.

The importance of the Rigveda for the study of early Indo-Aryan historical linguistics cannot be underestimated. ... its language is ... notably similar in many respects to the most archaic poetic texts of related language families, the Old Avestan Gathas and Homer's Iliad and Odyssey, respectively the earliest poetic representatives of the Iranian and Greek language families. Moreover, its manner of preservation, by a system of oral transmission which has preserved the hymns almost without change for 3,000 years, makes it a very trustworthy witness to the Indo-Aryan language of North India in the second millennium BC. Its importance for the reconstruction of Proto-Indo-European, particularly in respect of the archaic morphology and syntax it preserves, ... is considerable. Any linguistic investigation into Old Indo-Aryan, Indo-Iranian, or Proto-Indo-European cannot avoid treating the evidence of the Rigveda as of vital importance.

- ^ Klaus Klostermaier (1984). Mythologies and Philosophies of Salvation in the Theistic Traditions of India. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-88920-158-3. Archived from the original on 7 September 2023. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ Lester Kurtz (2015), Gods in the Global Village, SAGE Publications, ISBN 978-1-4833-7412-3, p. 64, Quote: "The 1,028 hymns of the Rigveda are recited at initiations, weddings and funerals...."

Previous Page Next Page