Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

Islamic views on slavery

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labour and slavery |

|---|

|

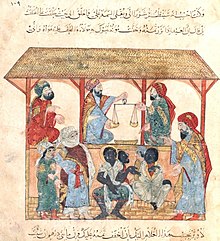

Islamic views on slavery represent a complex and multifaceted body of Islamic thought,[1][2] with various Islamic groups and thinkers espousing views on the matter which have been radically different throughout history.[3] Slavery existed in pre-Islamic Arabia, and Muhammad himself was a slave owner who never expressed any intention of abolishing the practice.[4][5][6] However, his teachings put a significant emphasis on improving the condition of slaves, and he exhorted his followers to treat them more humanely. As a consequence, slavery was recognised as a valid institution in the traditional Islamic jurisprudence, subject to certain conditions and rules.[1][7][8][7]

Early Islamic dogma allowed enslavement of other human beings with the exception of the free members of Islamic society, including non-Muslims (dhimmis), and set out to regulate and improve the conditions of human bondage. The sharīʿah (divine law) regarded as legal slaves only those non-Muslims who were imprisoned or bought beyond the borders of Islamic rule, or the sons and daughters of slaves already in captivity.[7] It also allowed men to have sexual relationships with slave women without the requirement of "nikah".[9] In later classical Islamic law, the topic of slavery is covered at great length.[3] Slaves, be they Muslim or those of any other religion, were equal to their fellow practitioners in religious issues.[10] However, the consent of a slave for sex, for withdrawal before ejaculation (azl) or to marry her off to someone else, was historically not considered necessary.[11] In theory, slavery in Islamic law does not have a racial or color component, although this has not always been the case in practice.[12] Slaves played various social and economic roles, from domestic worker to high-ranking positions in the government. Moreover, slaves were widely employed in irrigation, mining, pastoralism, and the army.[13] In some cases, the treatment of slaves was so harsh that it led to uprisings, such as the Zanj Rebellion.[14][15]

The hadiths, which differ between Shia and Sunni,[16] address slavery extensively, assuming its existence as part of society but viewing it as an exceptional condition and restricting its scope.[17][18] The hadiths forbade enslavement of dhimmis, the non-Muslims of Islamic society, and Muslims. They also regarded slaves as legal only when they were non-Muslims who were imprisoned, bought beyond the borders of Islamic rule, or the sons and daughters of slaves already in captivity.[18]

The Muslim slave trade was most active in West Asia, Eastern Europe, and Sub-Saharan Africa.[21] After the Trans-Atlantic slave trade had been suppressed, the ancient Trans-Saharan slave trade, the Indian Ocean slave trade and the Red Sea slave trade continued to traffic slaves from the African continent to the Middle East.[21] Estimates vary widely, with some suggesting up to 17 million slaves to the coast of the Indian Ocean, the Middle East, and North Africa.[22] Abolitionist movements began to grow during the 19th century, prompted by both Muslim reformers and diplomatic pressure from Britain. The first Muslim country to prohibit slavery was Tunisia, in 1846.[23] During the 19th and early 20th centuries all large Muslim countries, whether independent or under colonial rule, banned the slave trade and/or slavery. The Dutch East Indies abolished slavery in 1860 but effectively ended in 1910, while British India abolished slavery in 1862.[24] The Ottoman Empire banned the African slave trade in 1857 and the Circassian slave trade in 1908,[25] while Egypt abolished slavery in 1895, Afghanistan in 1921 and Persia in 1929.[26] In some Muslim countries in the Arabian peninsula and Africa, slavery was abolished in the second half of the 20th century: 1962 in Saudi Arabia and Yemen, Oman in 1970, Mauritania in 1981.[27] However, slavery has been documented in recent years, despite its illegality, in Muslim-majority countries in Africa including Chad, Mauritania, Niger, Mali, and Sudan.[28][29]

One notable example is Bilal ibn Rabah al-Habashi, who is noted for being the first Muezzin.[30] In modern times, various Muslim organizations reject the permissibility of slavery and it has since been abolished by all Muslim majority countries.[31] With abolition of slavery in the Muslim world, the practice of slavery came to an end.[32] Many modern Muslims see slavery as contrary to Islamic principles of justice and equality, however, Islam had a different system of slavery, that involved many intricate rules on how to handle slaves.[33][34] However, there are Islamic extremist groups and terrorist organizations who have revived the practice of slavery while they were active.[35]

- ^ a b Brockopp, Jonathan E., “Slaves and Slavery”, in: Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān, General Editor: Jane Dammen McAuliffe, Georgetown University, Washington DC.

- ^ Brunschvig, R., “ʿAbd”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs.

- ^ a b Lewis 1994, Ch.1 Archived 2001-04-01 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Gordon 1989.

- ^ Levy, Reuben (2000). "Slavery in Islam". The Social Structure of Islam. NY: Routledge. pp. 73–90. ISBN 978-0415209106.

- ^ https://www.brandeis.edu/projects/fse/muslim/slavery.html

- ^ a b c Dror Ze’evi (2009). "Slavery". In John L. Esposito (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2017-02-23. Retrieved 2017-02-23.

- ^ Brunschvig. 'Abd; Encyclopedia of Islam

- ^ https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/the-truth-about-muslims-and-sex-slavery-according-to-the-quran-rather-than-isis-or-islamophobes-a6875446.html%3Famp&ved=2ahUKEwiFyYubwqvpAhVrThUIHX-ZDxAQFjAEegQIBBAB&usg=AOvVaw1G3Py-_GoYBqsPdxjD7ad_&cf=1

- ^ See: Martin (2005), pp.150 and 151; Clarence-Smith (2006), p.2

- ^ Ali, Kecia (20 January 2017). "Concubinage and Consent". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 49 (1). Cambridge University Press (CUP): 148–152. doi:10.1017/s0020743816001203. ISSN 0020-7438.

- ^ Bernard Lewis, Race and Color in Islam, Harper and Row, 1970, quote on page 38. The brackets are displayed by Lewis.

- ^ Behrens-Abouseif, Doris. Cairo of the Mamluks: A History of Architecture and Its Culture. New York: Macmillan, 2008.

- ^ Clarence-Smith (2006), pp.2-5

- ^ William D. Phillips (1985). Slavery from Roman times to the early transatlantic trade. Manchester University Press. p. 76. ISBN 0-7190-1825-0.

- ^ "Development of History and Hadith Collections". www.al-islam.org. 2013-11-12. Retrieved 2024-08-31.

- ^ "Sahih Bukhari | Chapter: 48 | Manumission of Slaves". ahadith.co.uk. Retrieved 2024-08-31.

- ^ a b "BBC - Religions - Islam: Slavery in Islam". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2024-08-31.

- ^ Jonathan E. Brockopp (2000), Early Mālikī Law: Ibn ʻAbd Al-Ḥakam and His Major Compendium of Jurisprudence, Brill, ISBN 978-9004116283, pp. 131

- ^ Levy (1957) p. 77

- ^ a b La Rue, George M. (17 August 2023). "Indian Ocean and Middle Eastern Slave Trades". Oxford Bibliographies Online. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/OBO/9780199846733-0051. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- ^ "Focus on the slave trade". May 25, 2017. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- ^ Montana, Ismael (2013). The Abolition of Slavery in Ottoman Tunisia. University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0813044828.

- ^ Clarence-Smith 2006, pp. 120–122.

- ^ Erdem, Y. Hakan (1996). Slavery in the Ottoman Empire and its Demise, 1800-1909. Macmillan. pp. 95–151. ISBN 0333643232.

- ^ Clarence-Smith 2006, pp. 110–116.

- ^ Martin A. Klein (2002), Historical Dictionary of Slavery and Abolition, Page xxii, ISBN 0810841029

- ^ Segal, page 206. See later in article.

- ^ Segal, page 222. See later in article.

- ^ Robinson, David (2004-01-12). Muslim Societies in African History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-53366-9.

- ^ "University of Minnesota Human Rights Library". 2018-11-03. Archived from the original on 2018-11-03. Retrieved 2024-08-30.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Cortese 2013.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

eoqwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Ali 2006, pp. 53–54: "...the practical limitations of the Prophet’s mission meant that acquiescence to slave ownership was necessary, though distasteful, but meant to be temporary."

- ^ "ISIS and Their Use of Slavery". International Centre for Counter-Terrorism - ICCT. Retrieved 2024-08-30.

Previous Page Next Page