Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

Anti-Catholicism

| Freedom of religion |

|---|

| Religion portal |

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Persecutions of the Catholic Church |

|---|

|

|

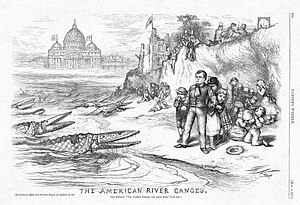

Anti-Catholicism, also known as Catholophobia,[1] is hostility towards Catholics and opposition to the Catholic Church, its clergy, and its adherents.[2] At various points after the Reformation, many majority-Protestant states, including England, Northern Ireland, Prussia and Germany, Scotland, and the United States, turned anti-Catholicism, opposition to the authority of Catholic clergy (anti-clericalism), opposition to the authority of the pope (anti-papalism), mockery of Catholic rituals, and opposition to Catholic adherents into major political themes and policies of religious discrimination and religious persecution.[3] Major examples of groups that have targeted Catholics in recent history include Ulster loyalists in Northern Ireland during the Troubles and the second Ku Klux Klan in the United States. The anti-Catholic sentiment which resulted from this trend frequently led to religious discrimination against Catholic communities and individuals and it occasionally led to the religious persecution of them (frequently, they were derogatorily referred to as "papists" or "Romanists" in Anglophone and Protestant countries). Historian John Wolffe identifies four types of anti-Catholicism: constitutional-national, theological, popular and socio-cultural.[4]

Historically, Catholics who lived in Protestant countries were frequently suspected of conspiring against the state in furtherance of papal interests. Their support of the alien pope led to allegations that they lacked loyalty to the state. In majority Protestant countries which experienced large scale immigration, such as the United States and Australia, suspicion of Catholic immigrants and/or discrimination against them frequently overlapped or was conflated with nativist, xenophobic, ethnocentric and/or racist sentiments (e.g. anti-Irish sentiment, anti-Filipino sentiment, anti-Italianism, anti-Spanish sentiment, and anti-Slavic sentiment, specifically anti-Polish sentiment).

In the early modern period, the Catholic Church struggled to maintain its traditional religious and political role in the face of rising secular power in Catholic countries. As a result of these struggles, a hostile attitude towards the considerable political, social, spiritual and religious power of the Pope and the clergy arose in majority Catholic countries in the form of anti-clericalism. The Inquisition was a favorite target of attack. After the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789, anti-clerical forces gained strength in some primarily Catholic nations, such as France, Spain, Mexico, and certain regions of Italy (especially in Emilia-Romagna). Certain political parties in these historically Catholic regions subscribed to and propagated an internal form of anti-Catholicism, generally known as anti-clericalism, that expressed a hostile attitude towards the Catholic Church as an establishment and the overwhelming political, social, spiritual and religious power of the Catholic Church. Anti-clerical governments often attacked the Pope's ability to appoint bishops in order to ensure that the Church would not be independent from the State, confiscated Church property, expelled Catholic religious orders such as the Jesuits, banned Classical Christian education, and sought to replace it with a State-controlled school system.[5]

- ^ Killeen, Jarlath (2014). The Emergence of Irish Gothic Fiction. ISBN 978-0-7486-9080-0. JSTOR 10.3366/j.ctt9qdrh2.

- ^ Anti-catholicism. Dictionary.com. WordNet 3.0. Princeton University. (accessed: November 13, 2008).

- ^ Mehmet Karabela (2021). Islamic Thought Through Protestant Eyes. New York: Routledge. pp. 1–10. ISBN 978-0-367-54954-1.

- ^ John Wolffe, "A Comparative Historical Categorisation of Anti-Catholicism." Journal of Religious History 39.2 (2015): 182–202.

- ^ John W. O'Malley SJ, The Jesuits: A History from Ignatius to the Present (2017).[ISBN missing][page needed]

Previous Page Next Page