Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

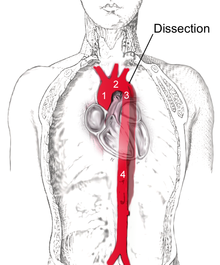

Aortic dissection

| Aortic dissection | |

|---|---|

| |

| Stanford type B dissection of the descending part of the aorta (3), which starts from the left subclavian artery and extends to the abdominal aorta (4). The ascending aorta (1) and aortic arch (2) shown in the image are not involved in this condition. | |

| Specialty | Vascular surgery, cardiothoracic surgery |

| Symptoms | severe chest or back pain, vomiting, sweating, lightheadedness[1][2] |

| Complications | Stroke, mesenteric ischemia, myocardial ischemia, aortic rupture[2] |

| Usual onset | Sudden[1][2] |

| Risk factors | High blood pressure, Marfan syndrome, Loeys-Dietz Syndrome, Turner syndrome, bicuspid aortic valve, previous heart surgery, major trauma, smoking[1][2][3] |

| Diagnostic method | Medical imaging[1] |

| Prevention | Blood pressure control, not smoking [1] |

| Treatment | Depends on the type[1] |

| Prognosis | Mortality without treatment 10% (type B), 50% (type A)[3] |

| Frequency | 3 per 100,000 per year[3] |

Aortic dissection (AD) occurs when an injury to the innermost layer of the aorta allows blood to flow between the layers of the aortic wall, forcing the layers apart.[3] In most cases, this is associated with a sudden onset of agonizing chest or back pain, often described as "tearing" in character.[1][2] Vomiting, sweating, and lightheadedness may also occur.[2] Damage to other organs may result from the decreased blood supply, such as stroke, lower extremity ischemia, or mesenteric ischemia.[2] Aortic dissection can quickly lead to death from insufficient blood flow to the heart or complete rupture of the aorta.[2]

AD is more common in those with a history of high blood pressure; a number of connective tissue diseases that affect blood vessel wall strength including Marfan syndrome and Ehlers–Danlos syndrome; a bicuspid aortic valve; and previous heart surgery.[2][3] Major trauma, smoking, cocaine use, pregnancy, a thoracic aortic aneurysm, inflammation of arteries, and abnormal lipid levels are also associated with an increased risk.[1][2] The diagnosis is suspected based on symptoms with medical imaging, such as CT scan, MRI, or ultrasound used to confirm and further evaluate the dissection.[1] The two main types are Stanford type A, which involves the first part of the aorta, and type B, which does not.[1]

Prevention is by blood pressure control and smoking cessation.[1] Management of AD depends on the part of the aorta involved.[1] Dissections that involve the first part of the aorta (adjacent to the heart) usually require surgery.[1][2] Surgery may be done either by an opening in the chest or from inside the blood vessel.[1] Dissections that involve the second part of the aorta can typically be treated with medications that lower blood pressure and heart rate, unless there are complications which then require surgical correction.[1][2]

AD is relatively rare, occurring at an estimated rate of three per 100,000 people per year.[1][3] It is more common in men than women.[1] The typical age at diagnosis is 63, with about 10% of cases occurring before the age of 40.[1][3] Without treatment, about half of people with Stanford type A dissections die within three days and about 10% of people with Stanford type B dissections die within one month.[3] The first case of AD was described in the examination of King George II of Great Britain following his death in 1760.[3] Surgery for AD was introduced in the 1950s by Michael E. DeBakey.[3]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Nienaber CA, Clough RE (28 February 2015). "Management of acute aortic dissection". The Lancet. 385 (9970): 800–811. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61005-9. PMID 25662791. S2CID 34347018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l White A, Broder J, Mando-Vandrick J, Wendell J, Crowe J (2013). "Acute aortic emergencies – part 2: aortic dissections". Advanced Emergency Nursing Journal. 35 (1): 28–52. doi:10.1097/tme.0b013e31827145d0. PMID 23364404.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Criado FJ (2011). "Aortic dissection: a 250-year perspective". Texas Heart Institute Journal. 38 (6): 694–700. PMC 3233335. PMID 22199439.

Previous Page Next Page