Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

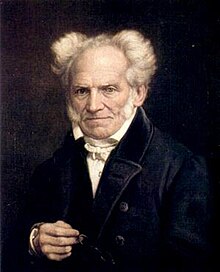

Arthur Schopenhauer's aesthetics

Arthur Schopenhauer's aesthetics result from his philosophical doctrine of the primacy of the metaphysical Will as the Kantian thing-in-itself, the ground of life and all being. In his chief work, The World as Will and Representation, Schopenhauer thought that if consciousness or attention is fully engrossed, absorbed, or occupied with the world as painless representations or images, then there is no consciousness of the world as painful willing. Aesthetic contemplation of a work of art provides just such a state—a temporary liberation from the suffering that results from enslavement to the will [need, craving, urge, striving] by becoming a will-less spectator of "the world as representation" [mental image or idea].[1][2] Art, according to Schopenhauer, also provides essential knowledge of the world's objects in a way that is more profound than science or everyday experience.[3]

Schopenhauer's aesthetic theory is introduced in Book 3 of The World as Will and Representation, Vol. 1, and developed in essays in the second volume. He provides an explanation of the beautiful (German: Schönheit) and the sublime (Das Erhabene), a hierarchy among the arts (from architecture, landscape gardening, sculpture and painting, poetry, etc. all the way to music, the pinnacle of the arts since it is a direct expression of the will), and the nature of artistic genius.

Schopenhauer's aesthetic philosophy influenced artists and thinkers including composers Richard Wagner and Arnold Schoenberg, philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, and writers associated with the Symbolist movement (Charles Baudelaire, Paul Verlaine, Stéphane Mallarmé, etc.)

- ^ "...aesthetic pleasure in the beautiful consists, to a large extent, in the fact that, when we enter the state of pure contemplation, we are raised for the moment above all willing, above all desires and cares; we are, so to speak, rid of ourselves." (Schopenhauer, The World as Will and Representation, vol. I, § 68, Dover page 390)

- ^ Schopenhauer's Account of Aesthetic Experience. TJ Diffey - The British Journal of Aesthetics, 1990 - Br Soc Aesthetics

- ^ "[A]esthetics is at the heart of philosophy for Schopenhauer: art and aesthetic experience not only provide escape from an otherwise miserable existence, but attain an objectivity explicitly superior to that of science or ordinary empirical knowledge." "Knowledge and Tranquility: Schopenhauer on the Value of Art," Christopher Janaway, in Dale Jacquette (ed.), Schopenhauer, Philosophy and the Arts, ch. 2, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), p. 39.

Previous Page Next Page