Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

Atypical antipsychotic

| Atypical antipsychotic | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

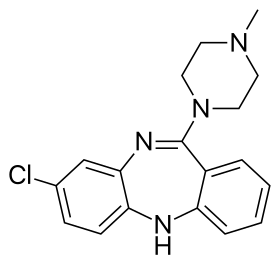

Skeletal formula of clozapine, the first atypical antipsychotic (1972) | |

| Synonyms | Second generation antipsychotic, serotonin–dopamine antagonist |

| Legal status | |

| In Wikidata | |

The atypical antipsychotics (AAP), also known as second generation antipsychotics (SGAs) and serotonin–dopamine antagonists (SDAs),[1][2] are a group of antipsychotic drugs (antipsychotic drugs in general are also known as tranquilizers and neuroleptics, although the latter is usually reserved for the typical antipsychotics) largely introduced after the 1970s and used to treat psychiatric conditions. Some atypical antipsychotics have received regulatory approval (e.g. by the FDA of the US, the TGA of Australia, the MHRA of the UK) for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, irritability in autism, and as an adjunct in major depressive disorder.

Both generations of medication tend to block receptors in the brain's dopamine pathways. Atypicals are less likely than haloperidol—the most widely used typical antipsychotic—to cause extrapyramidal motor control disabilities in patients such as unsteady Parkinson's disease–type movements, body rigidity, and involuntary tremors. However, only a few of the atypicals have been demonstrated to be superior to lesser-used, low-potency first-generation antipsychotics in this regard.[3][4][5]

As experience with these agents has grown, several studies have questioned the utility of broadly characterizing antipsychotic drugs as "atypical/second generation" as opposed to "first generation", noting that each agent has its own efficacy and side-effect profile. It has been argued that a more nuanced view in which the needs of individual patients are matched to the properties of individual drugs is more appropriate.[4][3] Although atypical antipsychotics are thought to be safer than typical antipsychotics, they still have severe side effects, including tardive dyskinesia (a serious movement disorder), neuroleptic malignant syndrome, and increased risk of stroke, sudden cardiac death, blood clots, and diabetes. Significant weight gain may occur. Critics have argued that "the time has come to abandon the terms first-generation and second-generation antipsychotics, as they do not merit this distinction."[6]

- ^ Miyake N, Miyamoto S, Jarskog LF (October 2012). "New serotonin/dopamine antagonists for the treatment of schizophrenia: are we making real progress?". Clinical Schizophrenia & Related Psychoses. 6 (3): 122–33. doi:10.3371/CSRP.6.3.4. PMID 23006237.

- ^ Sadock BJ, Sadock, Virginia A., Ruiz, Pedro (2014). Kaplan & Sadock's Synopsis of Psychiatry: Behavioral Sciences/Clinical Psychiatry (11th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer. p. 318. ISBN 978-1-60913-971-1. OCLC 881019573.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

leuchtwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L, Mavridis D, Orey D, Richter F, et al. (September 2013). "Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis". Lancet. 382 (9896): 951–62. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60733-3. PMID 23810019. S2CID 32085212.

- ^ "A roadmap to key pharmacologic principles in using antipsychotics". Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 9 (6): 444–54. 2007. doi:10.4088/PCC.v09n0607. PMC 2139919. PMID 18185824.

- ^ Tyrer P, Kendall T (January 2009). "The spurious advance of antipsychotic drug therapy". Lancet. 373 (9657): 4–5. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61765-1. PMID 19058841. S2CID 19951248.

Previous Page Next Page