Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

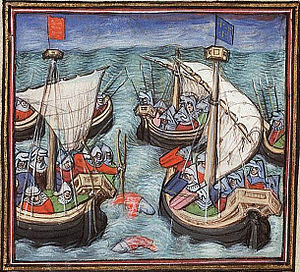

Battle of Arnemuiden

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2014) |

| Battle of Arnemuiden | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Hundred Years' War | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| England | France | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| John Kingston † |

Hugues Quiéret Nicolas Béhuchet | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 5 great cog (ship)s with artillery | 48 galleys | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,000 dead; 5 great cogs and their cargo captured | 900 dead and wounded | ||||||

The Battle of Arnemuiden was a naval battle fought on 23 September 1338 at the start of the Hundred Years' War between England and France. It was the first naval battle of the Hundred Years' War and the first recorded European naval battle using artillery, as the English ship Christopher had three cannons and one handgun.[1]

The battle featured a vast French fleet under admirals Hugues Quiéret and Nicolas Béhuchet against a small squadron of five great English cogs transporting an enormous cargo of wool to Antwerp, where Edward III of England was hoping to sell it, in order to be able to pay subsidies to his allies. It occurred near Arnemuiden, the port of the island of Walcheren (now in the Netherlands, but then part of the County of Flanders, formally part of the Kingdom of France). Overwhelmed by the superior numbers and with some of their crew still on shore, John Kingston, the commander of the squadron, surrendered after a day's fighting. [citation needed]

The French captured the rich cargo, took the five cogs into their fleet and massacred the English prisoners. The chronicles write:

Thus conquering did these said mariners of the king of France in this winter take great pillage, and especially they conquered the handsome great nef called the Christophe, all charged with the goods and wool that the English were sending to Flanders, which nef had cost the English king much to build: but its crew were lost to these Normans, and were put to death.

— Collection des chroniques nationales françaises écrites en langue vulgaire du treizième au seizième siècle, avec notes et éclaircissements par J. A. Buchon, p. 272.

- ^ Castex, Jean-Claude (2004). Dictionnaire des batailles navales franco-anglaises. Presses de l'Université Laval. p. 21. ISBN 9782763780610.

Previous Page Next Page