Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

Book of Joshua

| |||||

| Tanakh (Judaism) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Old Testament (Christianity) | |||||

|

|

|||||

| Bible portal | |||||

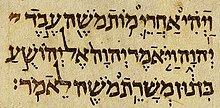

The Book of Joshua (Hebrew: סֵפֶר יְהוֹשֻׁעַ Sefer Yəhōšūaʿ, Tiberian: Sēp̄er Yŏhōšūaʿ;[1] Greek: Ιησούς του Ναυή; Latin: Liber Iosue) is the sixth book in the Hebrew Bible and the Old Testament, and is the first book of the Deuteronomistic history, the story of Israel from the conquest of Canaan to the Babylonian exile.[2]: 42 It tells of the campaigns of the Israelites in central, southern and northern Canaan, the destruction of their enemies, and the division of the land among the Twelve Tribes, framed by two set-piece speeches, the first by God commanding the conquest of the land, and, at the end, the second by Joshua warning of the need for faithful observance of the Law (torah) revealed to Moses.[3]

The strong consensus among scholars is that the Book of Joshua holds little historical value for early Israel and most likely reflects a much later period.[4] The earliest parts of the book are possibly chapters 2–11, the story of the conquest; these chapters were later incorporated into an early form of Joshua likely written late in the reign of king Josiah (reigned 640–609 BCE), but the book was not completed until after the fall of Jerusalem to the Neo-Babylonian Empire in 586 BCE, and possibly not until after the return from the Babylonian exile in 539 BCE.[5]: 10–11

Many scholars interpret the book of Joshua as referring to what would now be considered genocide.[6]

- ^ Khan, Geoffrey (2020). The Tiberian Pronunciation Tradition of Biblical Hebrew, Volume 1. Open Book Publishers. ISBN 978-1-78374-676-7.

- ^ McNutt, Paula (1999). Reconstructing the Society of Ancient Israel. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22265-9.

- ^ Achtemeier, Paul J; Boraas, Roger S (1996). The Harper Collins Bible Dictionary. Harper San Francisco. ISBN 978-0-06-060037-2.

- ^ Killebrew 2005, p. 152: "Almost without exception, scholars agree that the account in Joshua holds little historical value vis-à-vis early Israel and most likely reflects much later historical times.15"

- ^ Creach, Jerome F.D. (2003). Joshua. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-23738-7.

- ^ Sources for 'genocide':

- Lemos 2016, pp. 27–28: "Thus reads Deuteronomy 20:16–172—startling verses from a passage whose regulations on war are in many ways exemplified by the conquest narrative found in Joshua 1–12. Robert Coote has referred to these events as “an orgy of terror, violence, and mayhem.”3 Certainly, most contemporary readers recoil upon reading the account of the annihilation of Canaanite cities,4 and many scholars who have written on them have referred to the events described with the term “genocide.”5"

- Lemos, T. M. (2016). "Dispossessing Nations: Population Growth, Scarcity, and Genocide in Ancient Israel and Twentieth-Century Rwanda". In Olyan, Saul M. (ed.). Ritual Violence in the Hebrew Bible. Oxford University Press. pp. 27–66. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190249588.003.0003. ISBN 978-0-19-024958-8.

- Kiernan, Ben; Lemos, T.M.; Taylor, Tristan S. (2023). The Cambridge World History of Genocide: Volume 1, Genocide in the Ancient, Medieval and Premodern Worlds. Cambridge University Press. p. unpaginated. doi:10.1017/9781108655989. ISBN 978-1-108-64034-3. Retrieved 23 December 2024.

... genocidal violence while the Israelites were vassals of Mesopotamian empires. In fact, many scholars argue that Deuteronomy and Joshua were written during this time period. Although set in an idealised Mosaic past, what these most genocidal of biblical books were in actuality ...

- Fox, Everett (2014). The Early Prophets: Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings: The Schocken Bible, Volume II. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-8052-4323-9. Retrieved 23 December 2024.

- Olyan, Saul M. (2015). Ritual Violence in the Hebrew Bible: New Perspectives. Oxford University Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-19-024959-5. Retrieved 23 December 2024.

- Dever, William G. (2006). Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From?. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-8028-4416-3. Retrieved 23 December 2024.

- Avalos, Hector (2005). Fighting Words: The Origins of Religious Violence. G - Reference, Information and Interdisciplinary Subjects Series. Prometheus Books. pp. 143, 162. ISBN 978-1-59102-284-8. Retrieved 23 December 2024.

- Joseph, Simon J. (2014). The Nonviolent Messiah: Jesus, Q, and the Enochic Tradition. Fortress Press. p. unpaginated. ISBN 978-1-4514-8443-4. Retrieved 23 December 2024.

... many scholars now doubt the historicity of the conquest narratives of Joshua 6– 11,[67] the ethics of divinely mandated genocide are inescapably problematic.[68] There is simply no denying that the Torah's narratives of genocide ...

- Kaminsky, Joel S. (2016). Yet I Loved Jacob: Reclaiming the Biblical Concept of Election. Wipf & Stock Publishers. p. 114. ISBN 978-1-4982-8024-2. Retrieved 23 December 2024.

- Rae, Scott (2018). Moral Choices: An Introduction to Ethics. Zondervan Academic. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-310-53643-7. Retrieved 23 December 2024.

- Leuchter, Mark A.; Lamb, David T. (2016). The Historical Writings: Introducing Israel's Historical Literature. Introducing Israel's scriptures. Fortress Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-5064-0785-2. Retrieved 23 December 2024.

- Carvalho, Corrine; McLaughlin, John (2024). God and Gods in the Deuteronomistic History. Catholic Biblical Quarterly Imprints. Wipf & Stock Publishers. p. 30. doi:10.2307/j.ctv23khnsw.7. ISBN 978-1-6667-8760-3. Retrieved 23 December 2024.

- Earl, Douglas S. (2011). The Joshua Delusion: Rethinking Genocide in the Bible. James Clarke & Company Limited. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-227-90214-1. Retrieved 23 December 2024.

- Ruiten, Jacques van; Bekkum, Koert van (2020). Violence in the Hebrew Bible: Between Text and Reception. Oudtestamentische Studiën, Old Testament Studies. Brill. p. 145. ISBN 978-90-04-43468-4. Retrieved 23 December 2024.

- Trimm, Charlie (2021). Taylor, Tristan S. (ed.). A Cultural History of Genocide in the Ancient World. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. p. 38. doi:10.5040/9781350034686.ch-1. ISBN 978-1-350-03468-6.

Genocide scholars frequently refer to the biblical accounts in Joshua as genocidal without discussion, assuming that simply quoting the relevant texts will convince anyone of their identity as genocide (Chalk and Jonassohn 1990: 61–3; Moshman 2008: 82–3). Some biblical scholars who accept the historicity of the events agree with this assessment. For example, looking at the events from the perspective of the New Testament, C. S. Cowles argues that "a radical shift in the understanding of God's character and the sanctity of all human life occurred in between the days of the first Joshua and the second Joshua (i.e., Jesus) is beyond dispute" (2003: 41).

- Cohen, Shaye J. D. The Hebrew Bible Lecture 15. 0:42:00-0:45:00.

Previous Page Next Page