Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

Cyanide poisoning

| Cyanide poison | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Cyanide toxicity, hydrocyanic acid poison[1] |

| |

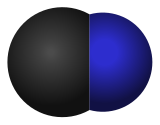

| Cyanide ion | |

| Specialty | Toxicology, critical care medicine |

| Symptoms | Early: headache, dizziness, fast heart rate, shortness of breath, vomiting[2] Later: seizures, slow heart rate, low blood pressure, loss of consciousness, cardiac arrest[2] |

| Usual onset | Few minutes[2][3] |

| Causes | Cyanide compounds[4] |

| Risk factors | House fire, metal polishing, certain insecticides, eating seeds such as from almonds[2][3][5] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, high blood lactate[2] |

| Treatment | Decontamination, supportive care (100% oxygen), hydroxocobalamin[2][3][6] |

Cyanide poisoning is poisoning that results from exposure to any of a number of forms of cyanide.[4] Early symptoms include headache, dizziness, fast heart rate, shortness of breath, and vomiting.[2] This phase may then be followed by seizures, slow heart rate, low blood pressure, loss of consciousness, and cardiac arrest.[2] Onset of symptoms usually occurs within a few minutes.[2][3] Some survivors have long-term neurological problems.[2]

Toxic cyanide-containing compounds include hydrogen cyanide gas and a number of cyanide salts, such as potassium cyanide.[2] Poisoning is relatively common following breathing in smoke from a house fire.[2] Other potential routes of exposure include workplaces involved in metal polishing, certain insecticides, the medication sodium nitroprusside, and certain seeds such as those of apples and apricots.[3][7][8] Liquid forms of cyanide can be absorbed through the skin.[9] Cyanide ions interfere with cellular respiration, resulting in the body's tissues being unable to use oxygen.[2]

Diagnosis is often difficult.[2] It may be suspected in a person following a house fire who has a decreased level of consciousness, low blood pressure, or high lactic acid.[2] Blood levels of cyanide can be measured but take time.[2] Levels of 0.5–1 mg/L are mild, 1–2 mg/L are moderate, 2–3 mg/L are severe, and greater than 3 mg/L generally result in death.[2]

If exposure is suspected, the person should be removed from the source of the exposure and decontaminated.[3] Treatment involves supportive care and giving the person 100% oxygen.[2][3] Hydroxocobalamin (vitamin B12a) appears to be useful as an antidote and is generally first-line.[2][6] Sodium thiosulphate may also be given.[2] Historically, cyanide has been used for mass suicide and it was used for genocide by the Nazis.[3][10]

- ^ Waters BL (2010). Handbook of Autopsy Practice (4 ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. p. 427. ISBN 978-1-59745-127-7. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Anseeuw K, Delvau N, Burillo-Putze G, De Iaco F, Geldner G, Holmström P, Lambert Y, Sabbe M (February 2013). "Cyanide poisoning by fire smoke inhalation: a European expert consensus". European Journal of Emergency Medicine. 20 (1): 2–9. doi:10.1097/mej.0b013e328357170b. PMID 22828651. S2CID 29844296.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hamel J (February 2011). "A review of acute cyanide poisoning with a treatment update". Critical Care Nurse. 31 (1): 72–81, quiz 82. doi:10.4037/ccn2011799. PMID 21285466.

- ^ a b Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (32 ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. 2011. p. 1481. ISBN 978-1-4557-0985-4. Archived from the original on 14 May 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ Ballhorn DJ (2011). "Cyanogenic Glycosides in Nuts and Seeds". Nuts and Seeds in Health and Disease Prevention. Elsevier. pp. 129–136. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-375688-6.10014-3. ISBN 978-0-12-375688-6.

- ^ a b Thompson JP, Marrs TC (December 2012). "Hydroxocobalamin in cyanide poisoning". Clinical Toxicology. 50 (10): 875–885. doi:10.3109/15563650.2012.742197. PMID 23163594. S2CID 25249847.

- ^ Hevesi D (26 March 1993). "Imported Bitter Apricot Pits Recalled as Cyanide Hazard". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 August 2017. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ "Sodium Nitroprusside". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ "Hydrogen Cyanide – Emergency Department/Hospital Management". CHEMM. 14 January 2015. Archived from the original on 14 November 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- ^ Longerich 2010, pp. 281–282.

Previous Page Next Page