Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

Defence of the Reich

| Defence of the Reich | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of European theatre of World War II | |||||||

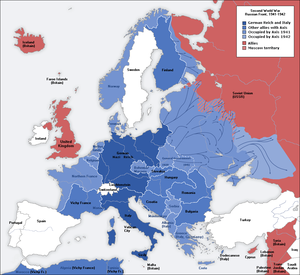

Scope of the Defence of the Reich campaign.[Note 1] | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Allies: |

Axis: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Ground-based, mid-1944:

1,612 light flak gun batteries:[4]

| |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

40,000 aircraft destroyed[5]

79,265 American airmen[5] |

57,405 aircraft destroyed[6] 97 submarines destroyed[7]7,400+ 88mm artillery pieces lost (1942–1944)[Note 2] at least 23,000 motor vehicles destroyed[9] At least 700–800 tanks[10] 500,000 civilians killed[5] 23,000 military and police killed[11] at least 450 locomotives (1943 only)[12] at least 4,500 passenger wagons (1943 only)[12] at least 6,500 goods wagons (1943 only)[12] | ||||||

The Defence of the Reich (German: Reichsverteidigung) is the name given to the strategic defensive aerial campaign fought by the Luftwaffe of Nazi Germany over German-occupied Europe and Germany during World War II against the Allied strategic bombing campaign. Its aim was to prevent the destruction of German civilians, military and civil industries by the Western Allies. The day and night air battles over Germany during the war involved thousands of aircraft, units and aerial engagements to counter the Allies bombing campaigns. The campaign was one of the longest in the history of aerial warfare and with the Battle of the Atlantic and the Allied naval blockade of Germany was the longest of the war. The Luftwaffe fighter force defended the airspace of German-occupied Europe against attack, first by RAF Bomber Command and then against the RAF and United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) in the Combined Bomber Offensive.

In the early years, the Luftwaffe was able to inflict a string of defeats on Allied strategic air forces. In 1939, Bomber Command was forced to operate at night, due to the extent of losses of unescorted bombers flying in daylight. In 1943, the USAAF suffered several reverses in daylight and called off the offensive over Germany in October limiting their attacks to western Europe as they built up their force. During the war the British built up their bomber force, introducing better aircraft with navigational aids and tactics such as the bomber stream that enabled them to mount larger and larger attacks while remaining within an acceptable loss rate. In 1944 the USAAF introduced metal drop tanks for all American fighters[13] including the newly arrived North American P-51D Mustang variant, which allowed fighter aircraft to escort USAAF bombers all the way to and from their targets. With a change of focus on destroying the German day fighter force, by the spring of 1944 the Eighth Air Force had achieved air supremacy over Western Europe which was essential for Allies so they could carry out the invasion of France.The strategic campaign against Germany eased as the Allies Transport Plan focused their resources on isolating northern France in preparation for the invasion.

American strategic bombing raids in June and July 1944 seriously damaged 24 synthetic oil plants and 69 refineries, which halted 98 per cent of Germany aviation fuel plants and dropped monthly synthetic oil production to 51,000 tons. After these attacks, recovery efforts in the following month could only bring back 65 per cent of aviation fuel production temporarily. In the first quarter of 1944, Nazi Germany produced 546,000 tons of aviation fuel, with 503,000 tons came from synthetic fuel by hydrogenation. Aviation fuel stock reserves had since dropped to 70 per cent in April 1944, to 370,000 tons in June 1944, and to 175,000 tons in November. The Oil campaign of World War II led to chronic fuel shortages, severe curtailment of flying training and accelerated deterioration in pilot quality, eroding the Luftwaffe's fighting capacity in the last months. By the end of the campaign, American forces claimed to have destroyed 35,783 enemy aircraft and the RAF claimed 21,622[citation needed], for a total of 57,405 German aircraft claimed destroyed.[Note 3]

The USAAF dropped 1.46 million tons of bombs on Axis-occupied Europe while the RAF dropped 1.31 million tons, for a total of 2.77 million tons, of which 51.1 per cent was dropped on Germany.[6] With the direct damage inflicted on Germany industry and air force, the Wehrmacht was forced to use millions of men, tens of thousands of guns and hundreds of millions of shells in a failed attempt to halt the Allied bomber Offensive.[15][Note 4][Note 5] The Luftwaffe's losses in this theater also sapped an enormous amount of Germany's overall warmaking potential: aircraft accounted for some 40% of German military expenditures (by Reichsmark value) from 1942 to 1944.[16]

From January 1942 to April 1943, German arms industry grew by an average of 5.5 per cent per month and by summer 1943, the systematic attack against German industry by Allied bombers brought the increase in armaments production from May 1943 to March 1944 to a halt.[17] At the ministerial meeting in January 1945, Albert Speer noted that, since the intensification of the bombing began, 35 per cent fewer tanks, 31 per cent fewer aircraft and 42 per cent fewer lorries were produced than planned because of the bombing. The German economy had to switch vast amount of resources away from equipment for the fighting fronts and assign them instead to combat the bombing threat.[18] The intensification of night bombing by the RAF and daylight attacks by the USAAF added to the destruction of a major part of German industries and cities, which caused the Nazi economy to collapse in the winter of 1944–45. By this time, the Allied armies had reached the German border and the strategic campaign became fused with the tactical battles over the front. The air campaign continued until April 1945, when the last strategic bombing missions were flown and it ended upon the German unconditional surrender on 9 May.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

- ^ Boog, Krebs & Vogel 2001a, pp. 246).

- ^ Caldwell & Muller 2007, p. 9.

- ^ a b c Westermann 2000, p. 499.

- ^ a b Askey 2017, p. 668.

- ^ a b c d Beaumont 1987, p. 13.

- ^ a b US Strategic Bombing Survey: Statistical Appendix to Overall Report (European War) (Feb 1947) table 1, p. X

- ^ Webster & Frankland 2006, p. 276.

- ^ Westermann 2001, p. 196.

- ^ Webster & Frankland 2006, p. 268.

- ^ Webster & Frankland 1961, p. 253.

- ^ Sperling 1956.

- ^ a b c Cox 1998, p. 115.

- ^ Bodie, Warren M. (1991). The Lockheed P-38 Lightning. Widewing Publications. ISBN 0-9629359-5-6.

- ^ Davis, Richard G (1993). Carl A. Spaatz and the Air War in Europe (PDF). Center for Air Force History. p. 685, 687.

- ^ Atkinson 2013, p. 350.

- ^ United States Strategic Bombing Survey Vol 3, Effects of Strategic Bombing on the German War Economy, 1945, p. 144.

- ^ Tooze 2006, pp. 556–557, 585, fig. 22.

- ^ Overy 2006, p. 160.

Cite error: There are <ref group=Note> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=Note}} template (see the help page).

Previous Page Next Page