Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

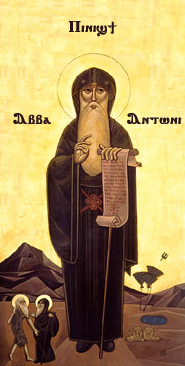

Desert Fathers

The Desert Fathers were early Christian hermits and ascetics, who lived primarily in the Scetes desert of the Roman province of Egypt, beginning around the third century AD. The Apophthegmata Patrum is a collection of the wisdom of some of the early desert monks and nuns, in print as Sayings of the Desert Fathers. The first Desert Father was Paul of Thebes, and the most well known was Anthony the Great, who moved to the desert in AD 270–271 and became known as both the father and founder of desert monasticism. By the time Anthony had died in AD 356, thousands of monks and nuns had been drawn to living in the desert following Anthony's example, leading his biographer, Athanasius of Alexandria, to write that "the desert had become a city."[1] The Desert Fathers had a major influence on the development of Christianity.

The desert monastic communities that grew out of the informal gathering of hermit monks became the model for Christian monasticism, first influencing the Coptic communities these monks were a part of and preached to.[2] Some were monophysites[2] or believed in a similar idea.

The eastern monastic tradition at Mount Athos and the western Rule of St. Benedict both were strongly influenced by the traditions that began in the desert. All of the monastic revivals of the Middle Ages looked to the desert for inspiration and guidance. Much of Eastern Christian spirituality, including the Hesychast movement, has its roots in the practices of the Desert Fathers. Even religious renewals such as the German evangelicals and Pietists in Pennsylvania, the Devotio Moderna movement, and the Methodist Revival in England are seen by modern scholars as being influenced by the Desert Fathers.[3]

- ^ Chryssavgis 2008, p. 15.

- ^ a b Olupona, Jacob K. (2014). African Religions: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-19-979058-6. OCLC 839396781.

- ^ Burton-Christie 1993, pp. 7–9.

Previous Page Next Page