Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

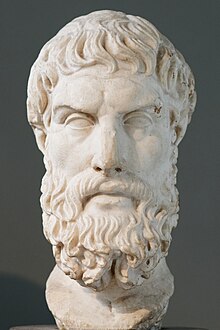

Epicurus

Epicurus | |

|---|---|

Roman marble bust of Epicurus | |

| Born | February 341 BC Samos, Greece |

| Died | 270 BC (aged about 72) Athens, Greece |

| Era | Hellenistic philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Epicureanism |

Main interests | |

Notable ideas | Attributed: |

Epicurus (/ˌɛpɪˈkjʊərəs/, EH-pih-KURE-əs;[2] Ancient Greek: Ἐπίκουρος Epikouros; 341–270 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher and sage who founded Epicureanism, a highly influential school of philosophy. He was born on the Greek island of Samos to Athenian parents. Influenced by Democritus, Aristippus, Pyrrho,[3] and possibly the Cynics, he turned against the Platonism of his day and established his own school, known as "the Garden", in Athens. Epicurus and his followers were known for eating simple meals and discussing a wide range of philosophical subjects. He openly allowed women and slaves[4] to join the school as a matter of policy. Of the over 300 works said to have been written by Epicurus about various subjects, the vast majority have been lost. Only three letters written by him—the letters to Menoeceus, Pythocles, and Herodotus—and two collections of quotes—the Principal Doctrines and the Vatican Sayings—have survived intact, along with a few fragments of his other writings. As a result of his work's destruction, most knowledge about his philosophy is due to later authors, particularly the biographer Diogenes Laërtius, the Epicurean Roman poet Lucretius and the Epicurean philosopher Philodemus, as well as the hostile but largely accurate accounts by the Pyrrhonist philosopher Sextus Empiricus, and the Academic Skeptic and statesman Cicero.

Epicurus asserted that philosophy's purpose is to attain as well as to help others attain happy (eudaimonic), tranquil lives characterized by ataraxia (peace and freedom from fear) and aponia (the absence of pain). He advocated that people were best able to pursue philosophy by living a self-sufficient life surrounded by friends. He taught that the root of all human neuroses is denial of death and the tendency for human beings to assume that death will be horrific and painful, which he claimed causes unnecessary anxiety, selfish self-protective behaviors, and hypocrisy. According to Epicurus, death is the end of both the body and the soul and therefore should not be feared. Epicurus taught that although the gods exist, they have no involvement in human affairs. He taught that people should act ethically not because the gods punish or reward them for their actions but because, due to the power of guilt, amoral behavior would inevitably lead to remorse weighing on their consciences and as a result, they would be prevented from attaining ataraxia.

Epicurus derived much of his physics and cosmology from the earlier philosopher Democritus (c. 460–c. 370 BC). Like Democritus, Epicurus taught that the universe is infinite and eternal and that all matter is made up of extremely tiny, invisible particles known as atoms. All occurrences in the natural world are ultimately the result of atoms moving and interacting in empty space. Epicurus deviated from Democritus by proposing the idea of atomic "swerve", which holds that atoms may deviate from their expected course, thus permitting humans to possess free will in an otherwise deterministic universe.

Though popular, Epicurean teachings were controversial from the beginning. Epicureanism reached the height of its popularity during the late years of the Roman Republic. It died out in late antiquity, subject to hostility from early Christianity. Throughout the Middle Ages, Epicurus was popularly, though inaccurately, remembered as a patron of drunkards, whoremongers, and gluttons. His teachings gradually became more widely known in the fifteenth century with the rediscovery of important texts, but his ideas did not become acceptable until the seventeenth century, when the French Catholic priest Pierre Gassendi revived a modified version of them, which was promoted by other writers, including Walter Charleton and Robert Boyle. His influence grew considerably during and after the Enlightenment, profoundly impacting the ideas of major thinkers, including John Locke, Thomas Jefferson, Jeremy Bentham, and Karl Marx.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

buyuwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

joneswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Diogenes Laertius, Book IX, Chapter 11, Section 64.

- ^ "Diogenes Laertius, Lives and Opinions of the Eminent Philosophers Book X Section 3".

Previous Page Next Page