Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

Era of Good Feelings

| Era of Good Feelings | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1815–1825 | |||

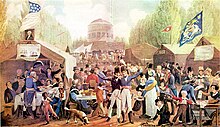

Independence Day Celebration in Centre Square by John Lewis Krimmel, 1819 | |||

| President(s) | James Monroe | ||

| Key events | Missouri Compromise Panic of 1819 Adams-Onis Treaty Monroe Doctrine | ||

Chronology

| |||

| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of the United States |

|---|

|

The Era of Good Feelings marked a period in the political history of the United States that reflected a sense of national purpose and a desire for unity among Americans in the aftermath of the War of 1812.[1][2] The era saw the collapse of the Federalist Party and an end to the bitter partisan disputes between it and the dominant Democratic-Republican Party during the First Party System.[3][4] President James Monroe strove to downplay partisan affiliation in making his nominations, with the ultimate goal of national unity and eliminating political parties altogether from national politics.[1][5][6] The period is so closely associated with Monroe's presidency (1817–1825) and his administrative goals that his name and the era are virtually synonymous.[7]

During and after the 1824 presidential election, the Democratic-Republican Party split between supporters and opponents of Jacksonian Democracy, leading to the Second Party System.

The designation of the period by historians as one of good feelings is often conveyed with irony or skepticism, as the history of the era was one in which the political atmosphere was strained and divisive, especially among factions within the Monroe administration and the Democratic-Republican Party.[3][8][9]

The phrase Era of Good Feelings was coined by Benjamin Russell in the Boston Federalist newspaper Columbian Centinel on July 12, 1817, following Monroe's visit to Boston, Massachusetts, as part of his good-will tour of the United States.[7][10][11]

- ^ a b Ammon 1971, p. 366

- ^ Wilentz 2008, p. 181

- ^ a b Ammon 1971, p. 4

- ^ Brown 1970, p. 23

- ^ Ammon 1971, p. 6

- ^ Dangerfield 1965, p. 24

- ^ a b Dangerfield 1965, p. 35

- ^ Remini 2002, p. 77

- ^ Dangerfield 1965, p. 32,35

- ^ Unger 2009, p. 271

- ^ Patricia L. Dooley, ed. (2004). The Early Republic: Primary Documents on Events from 1799 to 1820. Greenwood. pp. 298ff. ISBN 9780313320842. Archived from the original on January 20, 2023. Retrieved November 17, 2015.

Previous Page Next Page