Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

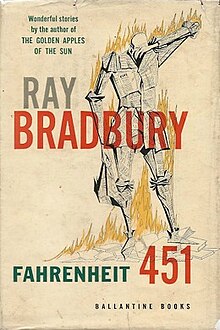

Fahrenheit 451

First edition cover (clothbound) | |

| Author | Ray Bradbury |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Joseph Mugnaini[1] |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Dystopian[2] |

| Published | October 19, 1953 (Ballantine Books)[3] |

| Publication place | United States |

| Pages | 156 |

| ISBN | 978-0-7432-4722-1 (current cover edition) |

| OCLC | 53101079 |

| 813.54 22 | |

| LC Class | PS3503.R167 F3 2003 |

Fahrenheit 451 is a 1953 dystopian novel by American writer Ray Bradbury.[4] It presents a future American society where books have been outlawed and "firemen" burn any that are found.[5] The novel follows in the viewpoint of Guy Montag, a fireman who soon becomes disillusioned with his role of censoring literature and destroying knowledge, eventually quitting his job and committing himself to the preservation of literary and cultural writings.

Fahrenheit 451 was written by Bradbury during the Second Red Scare and the McCarthy era, inspired by the book burnings in Nazi Germany and by ideological repression in the Soviet Union.[6] Bradbury's claimed motivation for writing the novel has changed multiple times. In a 1956 radio interview, Bradbury said that he wrote the book because of his concerns about the threat of burning books in the United States.[7] In later years, he described the book as a commentary on how mass media reduces interest in reading literature.[8] In a 1994 interview, Bradbury cited political correctness as an allegory for the censorship in the book, calling it "the real enemy these days" and labeling it as "thought control and freedom of speech control".[9]

The writing and theme within Fahrenheit 451 was explored by Bradbury in some of his previous short stories. Between 1947 and 1948, Bradbury wrote "Bright Phoenix", a short story about a librarian who confronts a "Chief Censor", who burns books. An encounter Bradbury had in 1949 with the police inspired him to write the short story "The Pedestrian" in 1951. In "The Pedestrian", a man going for a nighttime walk in his neighborhood is harassed and detained by the police. In the society of "The Pedestrian", citizens are expected to watch television as a leisurely activity, a detail that would be included in Fahrenheit 451. Elements of both "Bright Phoenix" and "The Pedestrian" would be combined into The Fireman, a novella published in Galaxy Science Fiction in 1951. Bradbury was urged by Stanley Kauffmann, an editor at Ballantine Books, to make The Fireman into a full novel. Bradbury finished the manuscript for Fahrenheit 451 in 1953, and the novel was published later that year.

Upon its release, Fahrenheit 451 was a critical success, albeit with notable dissenters; the novel's subject matter led to its censorship in apartheid South Africa and various schools in the United States. In 1954, Fahrenheit 451 won the American Academy of Arts and Letters Award in Literature and the Commonwealth Club of California Gold Medal.[10][11][12] It later won the Prometheus "Hall of Fame" Award in 1984[13] and a "Retro" Hugo Award in 2004.[14] Bradbury was honored with a Spoken Word Grammy nomination for his 1976 audiobook version.[15] The novel has also been adapted into films, stage plays, and video games. Film adaptations of the novel include a 1966 film directed by François Truffaut starring Oskar Werner as Guy Montag and a 2018 television film directed by Ramin Bahrani starring Michael B. Jordan as Montag, both of which received a mixed critical reception. Bradbury himself published a stage play version in 1979 and helped develop a 1984 interactive fiction video game of the same name, as well as a collection of his short stories titled A Pleasure to Burn.[16] Two BBC Radio dramatizations were also produced.

- ^ Crider, Bill (Fall 1980). Laughlin, Charlotte; Lee, Billy C. (eds.). "Ray Bradbury's FAHRENHEIT 451". Paperback Quarterly. III (3): 22. ISBN 978-1-4344-0633-0.

The first paperback edition featured illustrations by Joe Mugnaini and contained two stories in addition to the title tale: 'The Playground' and 'And The Rock Cried Out'.

- ^ Gerall, Alina; Hobby, Blake (2010). "Fahrenheit 451". In Bloom, Harold; Hobby, Blake (eds.). Civil Disobedience. Infobase Publishing. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-60413-439-1.

While Fahrenheit 451 begins as a dystopic novel about a totalitarian government that bans reading, the novel concludes with Montag relishing the book he has put to memory.

- ^ "Books Published Today". The New York Times: 19. October 19, 1953.

- ^ Reid, Robin Anne (2000). Ray Bradbury: A Critical Companion. Critical Companions to Popular Contemporary Writers. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 53. ISBN 0-313-30901-9.

Fahrenheit 451 is considered one of Bradbury's best works.

- ^ Seed, David (September 12, 2005). A Companion to Science Fiction. Blackwell Companions to Literature and Culture. Vol. 34. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publications. pp. 491–98. ISBN 978-1-4051-1218-5.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

bigread_burnwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Ray Bradbury (December 4, 1956). "Ticket to the Moon (tribute to SciFi)". Biography in Sound. Narrated by Norman Rose. NBC Radio News. 27:10–27:30. Archived from the original (mp3) on February 9, 2021. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

I wrote this book at a time when I was worried about the way things were going in this country four years ago. Too many people were afraid of their shadows; there was a threat of book burning. Many of the books were being taken off the shelves at that time.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

LAweeklywas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

:3was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Aggelis, Steven L., ed. (2004). Conversations with Ray Bradbury. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi. p. xxix. ISBN 1-57806-640-9.

...[in 1954 Bradbury received] two other awards—National Institute of Arts and Letters Award in Literature and Commonwealth Club of California Literature Gold Medal Award—for Fahrenheit 451, which is published in three installments in Playboy.

- ^ Davis, Scott A. "The California Book Awards Winners 1931-2012" (PDF). Commonwealth Club of California. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 28, 2021. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- ^ Nolan, William F. (May 1963). "BRADBURY: Prose Poet In The Age Of Space". The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. 24 (5). Mercury: 20.

Then there was the afternoon at Huston's Irish manor when a telegram arrived to inform Bradbury that his first novel, Fahrenheit 451, a bitterly-satirical story of the book-burning future, had been awarded a grant of $1,000 from the National Institute of Arts and Letters.

- ^ "Libertarian Futurist Society: Prometheus Awards, A Short History". Archived from the original on April 19, 2021. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ "1954 Retro Hugo Awards". July 26, 2007. Archived from the original on July 30, 2013. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ "19th Annual Grammy Awards Final Nominations". Billboard. Vol. 89, no. 3. Nielsen Business Media Inc. January 22, 1976. p. 110. ISSN 0006-2510.

- ^ Genzlinger, Neil (March 25, 2006). "Godlight Theater's 'Fahrenheit 451' Offers Hot Ideas for the Information Age". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 17, 2021. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

Previous Page Next Page