Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

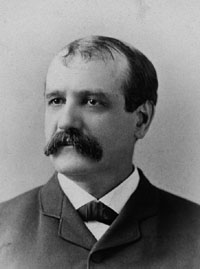

Francis Amasa Walker

Francis Amasa Walker | |

|---|---|

Francis Amasa Walker | |

| Born | July 2, 1840 |

| Died | January 5, 1897 (aged 56) Boston, Massachusetts |

| Resting place | Walnut Grove cemetery, North Brookfield, Massachusetts |

| Alma mater | Amherst College |

| Occupation(s) | Economist Statistician Civil servant Military officer University president |

| Known for | President of MIT (1881–1897) Superintendent of the 1870 and 1880 censuses Commissioner of Indian Affairs (1871–1872) |

| Board member of | American Statistical Association American Economic Association |

| Spouse | Exene Evelyn Stoughton |

| Children | 7 |

| Parent(s) | Hanna Ambrose (1803–1875) and Amasa Walker (1799–1879) |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | United States of America Union |

| Service | Union Army |

| Rank | |

| Battles / wars | American Civil War |

| 3rd President of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology | |

| In office 1881–1897 | |

| Preceded by | John Daniel Runkle |

| Succeeded by | James Crafts |

| Commissioner of the Bureau of Indian Affairs | |

| In office 1871–1872 | |

| President | Ulysses S. Grant |

| Preceded by | Ely S. Parker |

| Succeeded by | Edward Parmelee Smith |

| Signature | |

Francis Amasa Walker (July 2, 1840 – January 5, 1897) was an American economist, statistician, journalist, educator, academic administrator, and an officer in the Union Army.

Walker was born into a prominent Boston family, the son of the economist and politician Amasa Walker, and he graduated from Amherst College at the age of 20. He received a commission to join the 15th Massachusetts Infantry and quickly rose through the ranks as an assistant adjutant general. Walker fought in the Peninsula, Bristoe, Overland, and Richmond-Petersburg Campaigns before being captured by Confederate forces and held at the infamous Libby Prison. In July 1866, he was awarded the honorary grade of brevet brigadier general United States Volunteers, to rank from March 13, 1865, when he was 24 years old.[2]

Following the war, Walker served on the editorial staff of the Springfield Republican before using his family and military connections to gain appointment as the chief of the Bureau of Statistics from 1869 to 1870 and superintendent of the 1870 census where he published an award-winning Statistical Atlas visualizing the data for the first time. He joined Yale University's Sheffield Scientific School as a professor of political economy in 1872 and rose to international prominence serving as a chief member of the 1876 Philadelphia Exposition, American representative to the 1878 International Monetary Conference, President of the American Statistical Association in 1882, and inaugural president of the American Economic Association in 1886, and vice president of the National Academy of Sciences in 1890. Walker led the 1880 census which resulted in a twenty-two volume census, cementing Walker's reputation as the nation's preeminent statistician.

As an economist, Walker debunked the wage-fund doctrine and engaged in a prominent scholarly debate with Henry George on land, rent, and taxes. Walker argued in support of bimetallism and although he was an opponent of the nascent socialist movement, he argued that obligations existed between the employer and the employed. He published his International Bimetallism at the height of the 1896 presidential election campaign in which economic issues were prominent.[3] Walker was a prolific writer, authoring ten books on political economy and military history. In recognition of his contributions to economic theory, beginning in 1947, the American Economic Association recognized the lifetime achievement of an individual economist with a "Francis A. Walker Medal".

Walker accepted the presidency of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1881, a position he held for fifteen years until his death. During his tenure, he placed the institution on more stable financial footing by aggressively fund-raising and securing grants from the Massachusetts government, implemented many curricular reforms, oversaw the launch of new academic programs, and expanded the size of the Boston campus, faculty, and student enrollments. MIT's Walker Memorial Hall, a former students' clubhouse and one of the original buildings on the Charles River campus, was dedicated to him in 1916. Walker's reputation today is a subject of controversy due to his anti-immigration views, white supremacist views, and his brief association with the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs.[4][5][6]

- ^ Captured! The Civil War experience of the Superintendent of the Census Francis Amasa Walker by Jason G. Gauthier, Historian, Public Information Office, U.S. Census Bureau

- ^ Eicher & Eicher 2001, p. 760

- ^ Walker, Francis A. (1896). International Bimetallism. New York: Henry Holt and Company. Retrieved 11 June 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Leonard, Thomas C. (2005). "Retrospectives: Eugenics and Economics in the Progressive Era". The Journal of Economic Perspectives. 19 (4): 207–224. doi:10.1257/089533005775196642. ISSN 0895-3309. JSTOR 4134963.

- ^ Goldenweiser, E. A. (1912). "Walker's Theory of Immigration". American Journal of Sociology. 18 (3): 342–351. doi:10.1086/212097. ISSN 0002-9602. JSTOR 2763382.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

The Architecture of Race in American Immigration Lawwas invoked but never defined (see the help page).

Previous Page Next Page