Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

Gastrointestinal tract

| Gastrointestinal tract | |

|---|---|

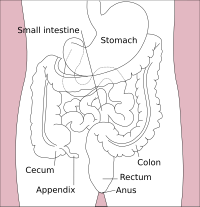

Diagram of the gastrointestinal tract in the average human | |

| Details | |

| System | Digestive system |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | tractus digestorius (mouth to anus), canalis alimentarius (esophagus to large intestine), canalis gastrointestinales (stomach to large intestine) |

| MeSH | D041981 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

|

| Major parts of the |

| Gastrointestinal tract |

|---|

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The GI tract contains all the major organs of the digestive system, in humans and other animals, including the esophagus, stomach, and intestines. Food taken in through the mouth is digested to extract nutrients and absorb energy, and the waste expelled at the anus as feces. Gastrointestinal is an adjective meaning of or pertaining to the stomach and intestines.

Most animals have a "through-gut" or complete digestive tract. Exceptions are more primitive ones: sponges have small pores (ostia) throughout their body for digestion and a larger dorsal pore (osculum) for excretion, comb jellies have both a ventral mouth and dorsal anal pores, while cnidarians and acoels have a single pore for both digestion and excretion.[1][2]

The human gastrointestinal tract consists of the esophagus, stomach, and intestines, and is divided into the upper and lower gastrointestinal tracts.[3] The GI tract includes all structures between the mouth and the anus,[4] forming a continuous passageway that includes the main organs of digestion, namely, the stomach, small intestine, and large intestine. The complete human digestive system is made up of the gastrointestinal tract plus the accessory organs of digestion (the tongue, salivary glands, pancreas, liver and gallbladder).[5] The tract may also be divided into foregut, midgut, and hindgut, reflecting the embryological origin of each segment. The whole human GI tract is about nine meters (30 feet) long at autopsy. It is considerably shorter in the living body because the intestines, which are tubes of smooth muscle tissue, maintain constant muscle tone in a halfway-tense state but can relax in spots to allow for local distention and peristalsis.[6][7]

The gastrointestinal tract contains the gut microbiota, with some 1,000 different strains of bacteria having diverse roles in the maintenance of immune health and metabolism, and many other microorganisms.[8][9][10] Cells of the GI tract release hormones to help regulate the digestive process. These digestive hormones, including gastrin, secretin, cholecystokinin, and ghrelin, are mediated through either intracrine or autocrine mechanisms, indicating that the cells releasing these hormones are conserved structures throughout evolution.[11]

- ^ "Overview of Invertebrates". www.ck12.org. 6 October 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ Ruppert EE, Fox RS, Barnes RD (2004). "Introduction to Bilateria". Invertebrate Zoology (7 ed.). Brooks / Cole. p. 197 [1]. ISBN 978-0-03-025982-1.

- ^ "gastrointestinal tract" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ Gastrointestinal+tract at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- ^ "digestive system" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ G., Hounnou; C., Destrieux; J., Desmé; P., Bertrand; S., Velut (2002-12-01). "Anatomical study of the length of the human intestine". Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy. 24 (5): 290–294. doi:10.1007/s00276-002-0057-y. ISSN 0930-1038. PMID 12497219. S2CID 33366428.

- ^ Raines, Daniel; Arbour, Adrienne; Thompson, Hilary W.; Figueroa-Bodine, Jazmin; Joseph, Saju (2014-05-26). "Variation in small bowel length: Factor in achieving total enteroscopy?". Digestive Endoscopy. 27 (1): 67–72. doi:10.1111/den.12309. ISSN 0915-5635. PMID 24861190. S2CID 19069407.

- ^ Lin, L; Zhang, J (2017). "Role of intestinal microbiota and metabolites on gut homeostasis and human diseases". BMC Immunology. 18 (1): 2. doi:10.1186/s12865-016-0187-3. PMC 5219689. PMID 28061847.

- ^ Marchesi, J. R; Adams, D. H; Fava, F; Hermes, G. D; Hirschfield, G. M; Hold, G; Quraishi, M. N; Kinross, J; Smidt, H; Tuohy, K. M; Thomas, L. V; Zoetendal, E. G; Hart, A (2015). "The gut microbiota and host health: A new clinical frontier". Gut. 65 (2): 330–339. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309990. PMC 4752653. PMID 26338727.

- ^ Clarke, Gerard; Stilling, Roman M; Kennedy, Paul J; Stanton, Catherine; Cryan, John F; Dinan, Timothy G (2014). "Minireview: Gut Microbiota: The Neglected Endocrine Organ". Molecular Endocrinology. 28 (8): 1221–38. doi:10.1210/me.2014-1108. PMC 5414803. PMID 24892638.

- ^ Nelson RJ. 2005. Introduction to Behavioral Endocrinology. Sinauer Associates: Massachusetts. p 57.

Previous Page Next Page