Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

Great Famine (Ireland)

| Great Famine An Gorta Mór | |

|---|---|

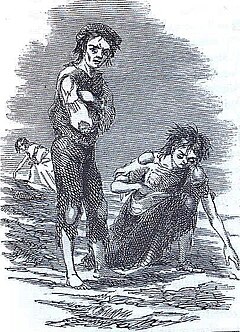

Scene at Skibbereen during the Great Famine by Cork artist James Mahony, The Illustrated London News, 1847 | |

| Location | Ireland |

| Period | 1845–1852 |

| Total deaths | 1 million |

| Causes | Policy failure, potato blight |

| Theory | Corn Laws, Gregory clause, Encumbered Estates' Court, Crime and Outrage Bill (Ireland) 1847, Young Irelander Rebellion of 1848, Three Fs, Poor Law Amendment Act |

| Relief | See below |

| Effect on demographics | Population fell by 20–25% due to death and emigration |

| Consequences | Permanent change in the country's demographic, political, and cultural landscape |

| Website | See list of memorials to the Great Famine |

| Preceded by | Irish Famine (1740–1741) (Bliain an Áir) |

| Succeeded by | Irish Famine, 1879 (An Gorta Beag) |

The Great Famine, also known as the Great Hunger (Irish: an Gorta Mór [ənˠ ˈɡɔɾˠt̪ˠə ˈmˠoːɾˠ]), the Famine and the Irish Potato Famine,[1][2] was a period of mass starvation and disease in Ireland lasting from 1845 to 1852 that constituted a historical social crisis and had a major impact on Irish society and history as a whole.[3] The most severely affected areas were in the western and southern parts of Ireland—where the Irish language was dominant—hence the period was contemporaneously known in Irish as an Drochshaol,[4] which literally translates to "the bad life" and loosely translates to "the hard times".

The worst year of the famine was 1847, which became known as "Black '47".[5][6] The population of Ireland on the eve of the famine was about 8.5 million; by 1901, it was just 4.4 million.[7] During the Great Hunger, roughly 1 million people died and more than 1 million more fled the country,[8] causing the country's population to fall by 20–25% between 1841 and 1871, with some towns' populations falling by as much as 67%.[9][10][11] Between 1845 and 1855, at least 2.1 million people left Ireland, primarily on packet ships but also on steamboats and barques—one of the greatest exoduses from a single island in history.[12][13]

The proximate cause of the famine was the infection of potato crops by blight (Phytophthora infestans)[14] throughout Europe during the 1840s. Blight infection caused 100,000 deaths outside Ireland and influenced much of the unrest that culminated in European Revolutions of 1848.[15] Longer-term reasons for the massive impact of this particular famine included the system of absentee landlordism[16][17] and single-crop dependence.[18][19] Initial limited but constructive government actions to alleviate famine distress were ended by a new Whig administration in London, which pursued a laissez-faire economic doctrine, but also because some in power believed in divine providence or that the Irish lacked moral character,[20][21] with aid only resuming to some degree later. Large amounts of food were exported from Ireland during the famine and the refusal of London to bar such exports, as had been done on previous occasions, was an immediate and continuing source of controversy, contributing to anti-British sentiment and the campaign for independence. Additionally, the famine indirectly resulted in tens of thousands of households being evicted, exacerbated by a provision forbidding access to workhouse aid while in possession of more than one-quarter acre of land.

The famine was a defining moment in the history of Ireland,[3] which was part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 1801 to 1922. The famine and its effects permanently changed the island's demographic, political, and cultural landscape, producing an estimated 2 million refugees and spurring a century-long population decline.[22][23][24][25] For both the native Irish and those in the resulting diaspora, the famine entered folk memory.[26] The strained relations between many Irish people and the then ruling British government worsened further because of the famine, heightening ethnic and sectarian tensions and boosting nationalism and republicanism both in Ireland and among Irish emigrants around the world. English documentary maker John Percival said that the famine "became part of the long story of betrayal and exploitation which led to the growing movement in Ireland for independence." Scholar Kirby Miller makes the same point.[27][28] Debate exists regarding nomenclature for the event, whether to use the term "Famine", "Potato Famine" or "Great Hunger", the last of which some believe most accurately captures the complicated history of the period.[29]

The potato blight returned to Europe in 1879 but, by this time, the Land War (one of the largest agrarian movements to take place in 19th-century Europe) had begun in Ireland.[30] The movement, organized by the Land League, continued the political campaign for the Three Fs which was issued in 1850 by the Tenant Right League during the Great Famine. When the potato blight returned to Ireland in the 1879 famine, the League boycotted "notorious landlords" and its members physically blocked the evictions of farmers; the consequent reduction in homelessness and house demolition resulted in a drastic reduction in the number of deaths.[31]

- ^ Kinealy 1994, p. 5.

- ^ O'Neill 2009, p. 1.

- ^ a b Kinealy 1994, p. xv.

- ^ [1]Archived 12 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine The great famine (An Drochshaol). Dúchas.ie

- ^ Éamon Ó Cuív, [2]Archived 17 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine An Gorta Mór – the impact and legacy of the Great Irish Famine

- ^ An Fháinleog Archived 18 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine Chapter 6. "drochshaol, while it can mean a hard life, or hard times, also, with a capital letter, has a specific, historic meaning: Bliain an Drochshaoil means The Famine Year, particularly 1847; Aimsir an Drochshaoil means the time of the Great Famine (1847–52)."

- ^ "Black '47 Ireland's Great Famine and its after-effects - Department of Foreign Affairs". www.dfa.ie. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ Ross 2002, p. 226.

- ^ Kinealy 1994, p. 357.

- ^ "Census of Ireland 1871 : Part I, Area, Population, and Number of Houses; Occupations, Religion and Education volume I, Province of Leinster". HMSO. 11 March 1872. Retrieved 11 March 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Carolan, Michael. Éireann's Exiles: Reconciling generations of secrets and separations. Archived 30 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine 3 April 2020. Accessed 15 January 2021.

- ^ James S. Donnelly Jr., The Great Irish Potato Famine (Thrupp, Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 2001) p. 181.

- ^ Hollett, David. Passage to the New World: packet ships and Irish famine emigrants, 1845–1851. United Kingdom, P.M. Heaton, 1995, p. 103.

- ^ Ó Gráda 2006, p. 7.

- ^ Ó Gráda, Cormac; Vanhaute, Eric; Paping, Richard (August 2006). The European subsistence crisis of 1845–1850: a comparative perspective (PDF). XIV International Economic History Congress of the International Economic History Association: Session 123. Helsinki. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 April 2017.

- ^ Laxton 1997, p. [page needed].

- ^ Litton 1994, p. [page needed].

- ^ Póirtéir 1995, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Fraser, Evan D. G. (30 October 2003). "Social vulnerability and ecological fragility: building bridges between social and natural sciences using the Irish Potato Famine as a case study". Conservation Ecology. 2 (7). Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- ^ "British History in depth: The Irish Famine". BBC History. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

- ^ "Racism and Anti-Irish Prejudice in Victorian England". victorianweb.org. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

- ^ Kelly, M.; Fotheringham, A. Stewart (2011). "The online atlas of Irish population change 1841–2002: A new resource for analysing national trends and local variations in Irish population dynamics". Irish Geography. 44 (2–3): 215–244. doi:10.1080/00750778.2011.664806.

population declining dramatically from 8.2 million to 6.5 million between 1841 and 1851 and then declining gradually and almost continuously to 4.5 million in 1961

- ^ "The Vanishing Irish: Ireland's population from the Great Famine to the Great War". 28 January 2013. Archived from the original on 12 May 2020. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ^ K. H. Connell, The Population of Ireland 1750–1845 (Oxford, 1951).[page needed]

- ^ T. Guinnane, The Vanishing Irish: Households, Migration, and the Rural Economy in Ireland, 1850–1914 (Princeton, 1997)[page needed]

- ^ Kinealy 1994, p. 342.

- ^ Percival, John (1995). Great Famine: Ireland's Potato Famine 1845–51. Diane Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0788169625. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Miller, Kerby A. Ireland and Irish America: Culture, Class, and Transatlantic Migration. Ireland, Field Day, 2008, p. 49.

- ^ Egan, Casey. The Irish Potato Famine, the Great Hunger, genocide – what should we call it? Potato blight played a role, but there was much more at play in Ireland's Great Hunger of 1845–1852. What should it be called? IrishCentral.com Archived 11 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine. 31 May 2015. Accessed 29 January 2021.

- ^ Tebrake, Janet K. (May 1992). "Irish peasant women in revolt: The Land League years". Irish Historical Studies. 28 (109): 63–80. doi:10.1017/S0021121400018587. S2CID 156376321.

- ^ Curtis, L. Perry (Lewis Perry) (11 June 2007). "The Battering Ram and Irish Evictions, 1887–90". Irish-American Cultural Institute. 42 (3): 207–228. doi:10.1353/eir.2007.0039. S2CID 161069346. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2018 – via Project MUSE.

Previous Page Next Page