Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

Great Game

| Part of a series on |

| New Imperialism |

|---|

|

| History |

| Theory |

| See also |

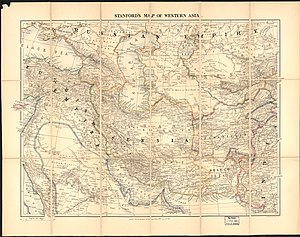

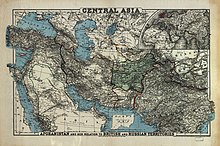

The Great Game was a rivalry between the 19th-century British and Russian empires over influence in Central Asia, primarily in Afghanistan, Persia, and Tibet. The two colonial empires used military interventions and diplomatic negotiations to acquire and redefine territories in Central and South Asia. Russia conquered Turkestan, and Britain expanded and set the borders of British India. By the early 20th century, a line of independent states, tribes, and monarchies from the shore of the Caspian Sea to the Eastern Himalayas were made into protectorates and territories of the two empires.

Though the Great Game was marked by distrust, diplomatic intrigue, and regional wars, it never erupted into a full-scale war directly between Russian and British colonial forces.[1] However, the two nations battled in the Crimean War from 1853 to 1856, which affected the Great Game.[2][3] The Russian and British Empires also cooperated numerous times during the Great Game, including many treaties and the Afghan Boundary Commission.

Britain feared Russia's southward expansion would threaten India, while Russia feared the expansion of British interests into Central Asia. As a result, Britain made it a high priority to protect all approaches to India, while Russia continued its military conquest of Central Asia.[1][3] Aware of the importance of India to the British, Russian efforts in the region often had the aim of extorting concessions from them in Europe,[2][4][5] but after 1801, they had no serious intention of directly attacking India.[6][2] Russian war plans for India that were proposed but never materialised included the Duhamel and Khrulev plans of the Crimean War (1853–1856).[7]

Russia and Britain's 19th-century rivalry in Asia began with the planned Indian March of Paul and Russian invasions of Iran in 1804–1813 and 1826–1828, shuffling Persia into a competition between colonial powers.[8] According to one major view, the Great Game started on 12 January 1830, when Lord Ellenborough, the president of the Board of Control for India, tasked Lord Bentinck, the governor-general, with establishing a trade route to the Emirate of Bukhara. Britain aimed to create a protectorate in Afghanistan, and support the Ottoman Empire, Persia, Khiva, and Bukhara as buffer states against Russian expansion. This would protect India and key British sea trade routes by blocking Russia from gaining a port on the Persian Gulf or the Indian Ocean. As Russian and British spheres of influence expanded and competed, Russia proposed Afghanistan as the neutral zone.[9]

Traditionally, the Great Game came to a close between 1895 and 1907. In September 1895, London and Saint Petersburg signed the Pamir Boundary Commission protocols, when the border between Afghanistan and the Russian Empire was defined using diplomatic methods.[10] In August 1907, the Anglo-Russian Convention created an alliance between Britain and Russia, and formally delineated control in Afghanistan, Persia, and Tibet.[11][12][13]

- ^ a b Ewans 2004, p. 1.

- ^ a b c Jelavich, Barbara (1974). St. Petersburg and Moscow : Tsarist and Soviet foreign policy, 1814–1974. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 200–201. ISBN 0-253-35050-6. OCLC 796911.

- ^ a b "The Great Game, 1856–1907: Russo-British Relations in Central and East Asia". reviews.history.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 10 April 2022. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:52was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

:42was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Schimmelpenninck van der Oye, David (2006). "Russian foreign policy: 1815–1917". The Cambridge History of Russia. Vol. 2. pp. 54–574.

- ^ Korbel, Josef (1966). Danger in Kashmir. Princeton, New Jersey. p. 277. ISBN 978-1-4008-7523-8. OCLC 927444240. Archived from the original on 24 January 2023. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Gozalova, Nigar (2023). "Qajar Iran at the centre of British–Russian confrontation in the 1820s". The Maghreb Review. 48 (1): 89–99. doi:10.1353/tmr.2023.0003. ISSN 2754-6772. S2CID 255523192.

- ^ Becker 2005, p. 47.

- ^ Morgan 1981, p. 231.

- ^ Dean, Riaz (2019). Mapping The Great Game: Explorers, Spies & Maps in Nineteenth-century Asia. Oxford: Casemate. pp. 270–71. ISBN 978-1-61200-814-1.

- ^ Meyer, Karl E. (10 August 1987). "The Editorial Notebook; Persia: The Great Game Goes On". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 18 August 2022. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ^ Hopkirk, Peter (2001). Setting the East Ablaze: On Secret Service in Bolshevik Asia. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280212-5. Archived from the original on 24 January 2023. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

Previous Page Next Page