Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

Ham House

| Ham House | |

|---|---|

Ham House in 2016, with Coade stone statue of Father Thames, by John Bacon the elder, in the foreground | |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Stuart |

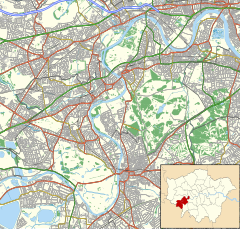

| Town or city | Ham, London |

| Country | England |

| Coordinates | 51°26′39″N 00°18′51″W / 51.44417°N 0.31417°W |

| Completed | 1610 |

| Client | Sir Thomas Vavasour |

| Owner | National Trust |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | William Samwell |

| Other information | |

| Parking | Ham Street |

| Website | |

| www | |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Designated | 10 January 1950 |

| Reference no. | 1080832 |

Ham House is a 17th-century house set in formal gardens on the bank of the River Thames in Ham, south of Richmond in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. The original house was completed in 1610 by Thomas Vavasour, an Elizabethan courtier and Knight Marshal to James I. It was then leased, and later bought, by William Murray, a close friend and supporter of Charles I. The English Civil War saw the house and much of the estate sequestrated, but Murray's wife Catherine regained them on payment of a fine. During the Protectorate his daughter Elizabeth Murray, Countess of Dysart on her father's death in 1655, successfully navigated the prevailing anti-royalist sentiment and retained control of the estate.

The house achieved its greatest period of prominence following Elizabeth's second marriage—to John Maitland, 1st Duke of Lauderdale, in 1672. The Lauderdales held important roles at the court of the restored Charles II, the Duke being a member of the Cabal ministry and holder of major positions in Scotland, while the Duchess exercised significant social and political influence. They began an ambitious program of development and embellishment at Ham. The house was almost doubled in size and equipped with private apartments for the Duke and Duchess, as well as princely accommodation suites for visitors. The house was furnished to the highest standards of courtly taste and decorated with "a lavishness which transcended even what was fitting to their exalted rank".[1] The Lauderdales accumulated notable collections of paintings, tapestries and furniture, and redesigned the gardens and grounds to reflect their status and that of their guests.

After the Duchess's death, the property passed through the line of her descendants. Occasionally, major alterations were made to the house, such as the reconstruction undertaken by Lionel Tollemache, 4th Earl of Dysart, in the 1730s. For the most part, later generations of owners focused on the preservation of the house and its collections. The family did not retain the high position at court held by the Lauderdales under Charles II, and a strain of family eccentricity and reserve saw the fifth Earl refuse a request from King George III to visit Ham. On the death of the 9th Earl – the last Earl to live at Ham – in 1935, the house passed to his second cousin, Lyonel; he and his son, Major (Cecil) Lyonel Tollemache, donated it to the National Trust in 1948. During the second half of the 20th century the house and gardens were opened to the public, and were extensively restored and researched. The property has become a popular filming location for cinema and television productions, which make use of its period interiors and gardens.

The house is built of red brick, and was originally constructed to a traditional Elizabethan era H-plan; the southern, garden frontage was infilled during the Lauderdales' rebuilding. The architect of Vavasour's house is unknown although drawings by Robert Smythson and his son John exist. The Lauderdales first consulted William Bruce, a cousin of the Duchess, but ultimately employed William Samwell to undertake their rebuilding. Ham retains many original Jacobean and Caroline features and furnishings, most in an unusually fine condition, and is a "rare survival of 17th-century luxury and taste".[2] The house is a Grade I listed building and received museum accreditation from Arts Council England in 2015. Its park and formal gardens are listed at Grade II*. Bridget Cherry, in the revised London: South Pevsner published in 2002, acknowledged that the exterior of Ham was "not as attractive as other houses of this period", but noted the interior's "high architectural and decorative interest".[3] The critic John Julius Norwich described the house as a "time machine – enclosing one in the elegant, opulent world of van Dyck and Lely".[4]

- ^ Beard 1985, p. 96.

- ^ "The History of Ham House". Ham House and Garden. National Trust. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ^ Cherry & Pevsner 2002, p. 474.

- ^ Norwich 1985, p. 360.

Previous Page Next Page