Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

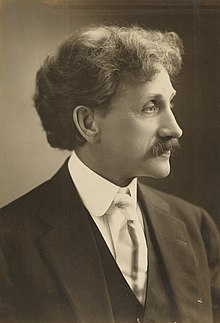

J. Howard Moore

J. Howard Moore | |

|---|---|

Moore, c. 1914 | |

| Born | John Howard Moore December 4, 1862 |

| Died | June 17, 1916 (aged 53) |

| Resting place | Excelsior Cemetery, Mitchell County, Kansas, U.S. 39°23′48″N 98°21′28″W / 39.3967018°N 98.3578033°W |

| Other names | "Silver tongue of Kansas" |

| Education | |

| Occupations |

|

| Known for | Animal rights and ethical vegetarianism advocacy |

| Notable work | The Universal Kinship (1906) |

| Spouse |

Louise Jesse "Jennie" Darrow

(m. 1899) |

| Relatives | Clarence Darrow (brother-in-law) |

| Signature | |

John Howard Moore (December 4, 1862 – June 17, 1916) was an American zoologist, philosopher, educator, and social reformer. He was best known for his advocacy of ethical vegetarianism and his pioneering role in the animal rights movement, both deeply influenced by his ethical interpretation of Darwin's theory of evolution. Moore's most influential work, The Universal Kinship (1906), introduced a sentiocentric philosophy he called the doctrine of Universal Kinship, arguing that the ethical treatment of animals, rooted in the Golden Rule, is essential for human ethical evolution, urging humans to extend their moral considerations to all sentient beings, based on their shared physical and mental evolutionary kinship.

A prominent figure during the Progressive Era, Moore was also heavily involved in the American humanitarian movement. He was a prolific writer, producing numerous articles, books, essays, and pamphlets on topics such as animal rights, ethics, evolutionary biology, humane education, humanitarianism, socialism, temperance, utilitarianism, and vegetarianism. In addition, he lectured extensively on these topics and was widely acclaimed for his oratory skills, earning the nickname the "silver tongue of Kansas" for his speeches on prohibition.

Born near Rockville, Indiana, Moore spent his early years in Linden, Missouri. Raised in a Christian household, he was raised to believe that animals existed entirely for human use. However, during his college years, Moore encountered Darwin's theory of evolution, which led him to reconsider his views, ultimately rejecting both Christianity and anthropocentrism and adopting vegetarianism. While studying zoology at the University of Chicago, he became a socialist, co-founded the university's Vegetarian Eating Club, and won a national oratorical contest on prohibition. Moore became an active member of the Chicago Vegetarian Society, modeled after the Humanitarian League, a British organization he also supported. In 1895, he delivered a speech titled "Why I Am a Vegetarian", which was later published by the Chicago Vegetarian Society. Moore spent the remainder of his life working as a teacher in Chicago while continuing to lecture and write.

In 1899, Moore published his first book, Better-World Philosophy, in which he addressed what he viewed as fundamental problems in the world and outlined his ideal vision for the universe. In The Universal Kinship (1906), Moore introduced his doctrine of Universal Kinship, which he later expanded upon in The New Ethics (1907). In response to an Illinois law requiring the teaching of morals in public schools, he produced educational materials, including two books and a pamphlet. He also authored two works on evolution: The Law of Biogenesis (1914) and Savage Survivals (1916). After battling chronic illness and depression for several years, Moore died by suicide at the age of 53 in Jackson Park, Chicago.

Previous Page Next Page