Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

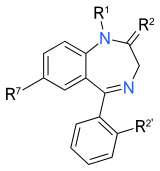

List of benzodiazepines

| Benzodiazepines |

|---|

|

The tables below contain a sample list of benzodiazepines and benzodiazepine analogs that are commonly prescribed, with their basic pharmacological characteristics, such as half-life and equivalent doses to other benzodiazepines, also listed, along with their trade names and primary uses. The elimination half-life is how long it takes for half of the drug to be eliminated by the body. "Time to peak" refers to when maximum levels of the drug in the blood occur after a given dose. Benzodiazepines generally share the same pharmacological properties, such as anxiolytic, sedative, hypnotic, skeletal muscle relaxant, amnesic, and anticonvulsant effects. Variation in potency of certain effects may exist amongst individual benzodiazepines. Some benzodiazepines produce active metabolites. Active metabolites are produced when a person's body metabolizes the drug into compounds that share a similar pharmacological profile to the parent compound and thus are relevant when calculating how long the pharmacological effects of a drug will last. Long-acting benzodiazepines with long-acting active metabolites, such as diazepam and chlordiazepoxide, are often prescribed for benzodiazepine or alcohol withdrawal as well as for anxiety if constant dose levels are required throughout the day. Shorter-acting benzodiazepines are often preferred for insomnia due to their lesser hangover effect.[1][2][3][4][5]

It is fairly important to note that elimination half-life of diazepam and chlordiazepoxide, as well as other long half-life benzodiazepines, is twice as long in the elderly compared to younger individuals. Due to increased sensitivity and potentially dangerous adverse events among elderly patients, it is recommended to avoid prescribing them as specified by the 2015 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria.[6] Individuals with an impaired liver also metabolize benzodiazepines more slowly. Thus, the approximate equivalent of doses below may need to be adjusted accordingly in individuals on short acting benzodiazepines who metabolize long-acting benzodiazepines more slowly and vice versa. The changes are most notable with long acting benzodiazepines as these are prone to significant accumulation in such individuals and can lead to withdrawal symptoms.[citation needed] For example, the equivalent dose of diazepam in an elderly individual on lorazepam may be half of what would be expected in a younger individual.[7][8] Equivalent doses of benzodiazepines differ as much as 20 fold.[9][10][11]

- ^ Golombok S, Lader M (August 1984). "The psychopharmacological effects of premazepam, diazepam and placebo in healthy human subjects". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 18 (2): 127–133. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1984.tb02444.x. PMC 1463527. PMID 6148956.

- ^ de Visser SJ, van der Post JP, de Waal PP, Cornet F, Cohen AF, van Gerven JM (January 2003). "Biomarkers for the effects of benzodiazepines in healthy volunteers". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 55 (1): 39–50. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.2002.t01-10-01714.x. PMC 1884188. PMID 12534639.

- ^ "Benzodiazepine Names". non-benzodiazepines.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2008-12-08. Retrieved 2009-04-05.

- ^ Ashton CH (March 2007). "Benzodiazepine Equivalence Table". benzo.org.uk. Retrieved 2009-04-05.

- ^ Hsiung R (July 1995). "Benzodiazepine Equivalence Charts". dr-bob.org. Archived from the original on 2009-02-09. Retrieved 2009-04-05.

- ^ By the American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel; et al. (American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel) (November 2015). "American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 63 (11): 2227–2246. doi:10.1111/jgs.13702. PMID 26446832. S2CID 38797655.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Salzman C (15 May 2004). Clinical geriatric psychopharmacology (4th ed.). USA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 450–453. ISBN 978-0-7817-4380-8.

- ^ Delcò F, Tchambaz L, Schlienger R, Drewe J, Krähenbühl S (2005). "Dose adjustment in patients with liver disease". Drug Safety. 28 (6): 529–545. doi:10.2165/00002018-200528060-00005. PMID 15924505. S2CID 9849818.

- ^ Riss J, Cloyd J, Gates J, Collins S (August 2008). "Benzodiazepines in epilepsy: pharmacology and pharmacokinetics". Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 118 (2): 69–86. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.2008.01004.x. PMID 18384456. S2CID 24453988.

- ^ Ashton H (July 1994). "Guidelines for the rational use of benzodiazepines. When and what to use". Drugs. 48 (1): 25–40. doi:10.2165/00003495-199448010-00004. PMID 7525193. S2CID 46966796.

- ^ "benzo.org.uk : Benzodiazepines: How They Work & How to Withdraw, Prof C H Ashton DM, FRCP, 2002". benzo.org.uk. Retrieved 2019-12-19.

Previous Page Next Page