Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

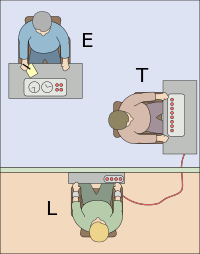

Milgram experiment

Beginning on August 7, 1961, a series of social psychology experiments were conducted by Yale University psychologist Stanley Milgram, who intended to measure the willingness of study participants to obey an authority figure who instructed them to perform acts conflicting with their personal conscience. Participants were led to believe that they were assisting an unrelated experiment, in which they had to administer electric shocks to a "learner". These fake electric shocks gradually increased to levels that would have been fatal had they been real.[2]

The experiments unexpectedly found that a very high proportion of subjects would fully obey the instructions, with every participant going up to 300 volts, and 65% going up to the full 450 volts. Milgram first described his research in a 1963 article in the Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology[1] and later discussed his findings in greater depth in his 1974 book, Obedience to Authority: An Experimental View.[3]

The experiments began on August 7, 1961 (after a grant proposal was approved in July), in the basement of Linsly-Chittenden Hall at Yale University, three months after the start of the trial of German Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem.[4][5] Milgram devised his psychological study to explain the psychology of genocide and answer the popular contemporary question: "Could it be that Eichmann and his million accomplices in the Holocaust were just following orders? Could we call them all accomplices?"[6]

While the experiment itself was repeated many times around the globe, with fairly consistent results, both its interpretations as well as its applicability to the Holocaust are disputed.[7][dubious – discuss][8]

- ^ a b Milgram, Stanley (1963). "Behavioral Study of Obedience". Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 67 (4): 371–8. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.599.92. doi:10.1037/h0040525. PMID 14049516. S2CID 18309531. Archived from the original on July 17, 2012. Retrieved November 20, 2006. as PDF. Archived April 4, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

blasswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Milgram, Stanley (1974). Obedience to Authority; An Experimental View. Harpercollins. ISBN 978-0-06-131983-9.

- ^ Thomas Blass, The Man Who Shocked the World: The Life and Legacy of Stanley Milgram (Basic Books, 2009) p. 75

- ^ Zimbardo, Philip. "When Good People Do Evil". Yale Alumni Magazine. Yale Alumni Publications, Inc. Archived from the original on May 2, 2015. Retrieved April 24, 2015.

- ^ Stanley Milgram, Obedience to Authority: An Experimental View (New York: Harper & Row, 1974) p. 123

- ^ Blass, Thomas (1991). "Understanding behavior in the Milgram obedience experiment: The role of personality, situations, and their interactions" (PDF). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 60 (3): 398–413. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.60.3.398. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 7, 2016.

- ^ Rutger, Bregman (2020). Humankind. Bloomsbury. pp. 161–180. ISBN 978-1-4088-9894-9.

Previous Page Next Page