Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

Nematode

| Nematode Temporal range: Possible Cambrian occurrence [2]

| |

|---|---|

| |

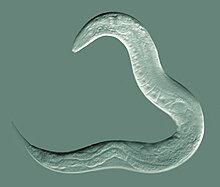

| Caenorhabditis elegans, a model species of roundworm | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Subkingdom: | Eumetazoa |

| Clade: | ParaHoxozoa |

| Clade: | Bilateria |

| Clade: | Nephrozoa |

| (unranked): | Protostomia |

| Superphylum: | Ecdysozoa |

| Clade: | Nematoida |

| Phylum: | Nematoda Diesing, 1861 |

| Classes | |

|

(see text) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The nematodes (/ˈnɛmətoʊdz/ NEM-ə-tohdz or NEEM-; Ancient Greek: Νηματώδη; Latin: Nematoda), roundworms or eelworms constitute the phylum Nematoda. Species in the phylum inhabit a broad range of environments. Most species are free-living, feeding on microorganisms, but many are parasitic. Parasitic worms (helminths) are the cause of soil-transmitted helminthiases.

They are classified along with arthropods, tardigrades and other moulting animals in the clade Ecdysozoa. Unlike the flatworms, nematodes have a tubular digestive system, with openings at both ends. Like tardigrades, they have a reduced number of Hox genes, but their sister phylum Nematomorpha has kept the ancestral protostome Hox genotype, which shows that the reduction has occurred within the nematode phylum.[3]

Nematode species can be difficult to distinguish from one another. Consequently, estimates of the number of nematode species are uncertain. A 2013 survey of animal biodiversity suggested there are over 25,000.[4][5] Estimates of the total number of extant species are subject to even greater variation. A widely referenced 1993 article estimated there might be over a million species of nematode.[6] A subsequent publication challenged this claim, estimating the figure to be at least 40,000 species.[7] Although the highest estimates (up to 100 million species) have since been deprecated, estimates supported by rarefaction curves,[8][9] together with the use of DNA barcoding[10] and the increasing acknowledgment of widespread cryptic species among nematodes,[11] have placed the figure closer to one million species.[12]

Nematodes have successfully adapted to nearly every ecosystem: from marine (salt) to fresh water, soils, from the polar regions to the tropics, as well as the highest to the lowest of elevations. They are ubiquitous in freshwater, marine, and terrestrial environments, where they often outnumber other animals in both individual and species counts, and are found in locations as diverse as mountains, deserts, and oceanic trenches. They are found in every part of the Earth's lithosphere,[13] even at great depths, 0.9–3.6 km (3,000–12,000 ft) below the surface of the Earth in gold mines in South Africa.[13] They represent 90% of all animals on the ocean floor.[14] In total, 4.4 × 1020 nematodes inhabit the Earth's topsoil, or approximately 60 billion for each human, with the highest densities observed in tundra and boreal forests.[15] Their numerical dominance, often exceeding a million individuals per square meter and accounting for about 80% of all individual animals on Earth, their diversity of lifecycles, and their presence at various trophic levels point to an important role in many ecosystems.[15][16] They play crucial roles in polar ecosystems.[17][18] The roughly 2,271 genera are placed in 256 families.[19] The many parasitic forms include pathogens in most plants and animals. A third of the genera occur as parasites of vertebrates; about 35 nematode species are human parasites.[19]

- ^ Poinar, George; Kerp, Hans; Hass, Hagen (January 2008). "Palaeonema phyticum gen. n., sp. n. (Nematoda: Palaeonematidae fam. n.), a Devonian nematode associated with early land plants". Nematology. 10 (1): 9–14. doi:10.1163/156854108783360159.

- ^ Maas, Andreas; Waloszek, Dieter; Haug, Joachim; Müller, Klaus (January 2007). "A possible larval roundworm from the Cambrian 'Orsten' and its bearing on the phylogeny of Cycloneuralia". Memoirs of the Association of Australasian Palaeontologists. 34: 499–519.

- ^ Baker, Emily A.; Woollard, Alison (2019). "How weird is the worm? Evolution of the developmental gene toolkit in Caenorhabditis elegans". Journal of Developmental Biology. 7 (4): 19. doi:10.3390/jdb7040019. PMC 6956190. PMID 31569401.

- ^ Hodda, M. (2011). Zhang, Z.-Q. (ed.). "Phylum Nematoda (Cobb, 1932)". Animal biodiversity: An outline of higher-level classification and survey of taxonomic richness. Zootaxa. 3148: 63–95. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3148.1.11.

- ^ Zhang, Z. (2013). Zhang, Z.-Q. (ed.). "Animal biodiversity: An update of classification and diversity in 2013". Animal biodiversity: An update of classification and diversity (Addenda 2013). Zootaxa. 3703 (1): 5–11. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3703.1.3.

- ^ Lambshead, P. John D. (January 1993). "Recent developments in marine benthic biodiversity research". Oceanis. 19 (6): 5–24. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- ^ Anderson, Roy C. (2000). Nematode Parasites of Vertebrates: Their Development and Transmission. CABI. pp. 1–2. doi:10.1079/9780851994215.0000. ISBN 978-0-85199-421-5. OCLC 559243334.

Estimates of 500,000 to a million species have no basis in fact.

- ^ Lambshead, P.J.; Boucher, G. (2003). "Marine nematode deep-sea biodiversity—hyperdiverse or hype?". Journal of Biogeography. 30 (4): 475–485. Bibcode:2003JBiog..30..475L. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2699.2003.00843.x. S2CID 86504164.

- ^ Qing, X.; Bert, W. (2019). "Family Tylenchidae (Nematoda): an overview and perspectives". Organisms Diversity & Evolution. 19 (3): 391–408. Bibcode:2019ODivE..19..391Q. doi:10.1007/s13127-019-00404-4. S2CID 190873905.

- ^ Floyd, Robin; Abebe, Eyualem; Papert, Artemis; Blaxter, Mark (2002). "Molecular barcodes for soil nematode identification". Molecular Ecology. 11 (4): 839–850. Bibcode:2002MolEc..11..839F. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294X.2002.01485.x. PMID 11972769. S2CID 12955921.

- ^ Derycke, S.; Sheibani Tezerji, R.; Rigaux, A.; Moens, T. (2012). "Investigating the ecology and evolution of cryptic marine nematode species through quantitative real-time PCR of the ribosomal ITS region". Molecular Ecology Resources. 12 (4): 607–619. doi:10.1111/j.1755-0998.2012.03128.x. hdl:1854/LU-3127487. PMID 22385909. S2CID 4818657.

- ^ Blaxter, Mark (2016). "Imagining Sisyphus happy: DNA barcoding and the unnamed majority". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B. 371 (1702): 20150329. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0329. PMC 4971181. PMID 27481781.

- ^ a b Borgonie, G.; García-Moyano, A.; Litthauer, D.; Bert, W.; Bester, A.; van Heerden, E.; Möller, C.; Erasmus, M.; Onstott, T. C. (June 2011). "Nematoda from the terrestrial deep subsurface of South Africa". Nature. 474 (7349): 79–82. Bibcode:2011Natur.474...79B. doi:10.1038/nature09974. hdl:1854/LU-1269676. PMID 21637257. S2CID 4399763.

- ^ Danovaro, Roberto; Gambi, Cristina; Dell'Anno, Antonio; Corinaldesi, Cinzia; Fraschetti, Simonetta; Vanreusel, Ann; Vincx, Magda; Gooday, Andrew J. (2008). "Exponential Decline of Deep-Sea Ecosystem Functioning Linked to Benthic Biodiversity Loss". Current Biology. 18 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.11.056. Retrieved 21 December 2024.

- ^ a b van den Hoogen, Johan; Geisen, Stefan; Routh, Devin; Ferris, Howard; Traunspurger, Walter; et al. (24 July 2019). "Soil nematode abundance and functional group composition at a global scale". Nature. 572 (7768): 194–198. Bibcode:2019Natur.572..194V. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1418-6. hdl:20.500.11755/c8c7bc6a-585c-4a13-9e36-4851939c1b10. PMID 31341281. S2CID 198492891. Archived from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ Platt, H.M. (1994). "foreword". In Lorenzen, S.; Lorenzen, S.A. (eds.). The phylogenetic systematics of freeliving nematodes. Ray Society (Series). Vol. 162. London, UK: Ray Society. ISBN 978-0-903874-22-9. OCLC 1440106662.

- ^ Lee, Charles K.; Laughlin, Daniel C.; Bottos, Eric M.; Caruso, Tancredi; Joy, Kurt; et al. (15 February 2019). "Biotic interactions are an unexpected yet critical control on the complexity of an abiotically driven polar ecosystem" (PDF). Communications Biology. 2 (1). doi:10.1038/s42003-018-0274-5. ISSN 2399-3642. PMC 6377621. PMID 30793041. Retrieved 21 December 2024.

- ^ Caruso, Tancredi; Hogg, Ian D.; Nielsen, Uffe N.; Bottos, Eric M.; Lee, Charles K.; Hopkins, David W.; Cary, S. Craig; Barrett, John E.; Green, T. G. Allan; Storey, Bryan C.; Wall, Diana H.; Adams, Byron J. (15 February 2019). "Nematodes in a polar desert reveal the relative role of biotic interactions in the coexistence of soil animals" (PDF). Communications Biology. 2 (1). doi:10.1038/s42003-018-0260-y. ISSN 2399-3642. PMC 6377602. PMID 30793042. Retrieved 21 December 2024.

- ^ a b Anderson, Roy C. (8 February 2000). Nematode Parasites of Vertebrates: Their development and transmission. CABI. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-85199-786-5.

Previous Page Next Page