Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

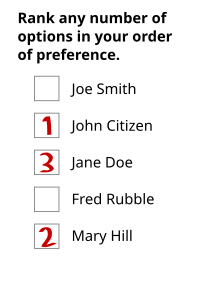

Optional preferential voting

One of the ways in which ranked voting systems vary is whether an individual vote must express a minimum number of preferences to avoid being considered invalid ("spoiled" or "informal" or "rejected").

Possibilities are:

- Full preferential voting (FPV) requires all candidates to be ranked

- Optional preferential voting (OPV) requires only one candidate, the voter's first preference, to be indicated

- Semi-optional preferential voting requires ranking more than one candidate but not necessary to rank all the candidates.

Ranked-voting systems typically use a ballot paper in which the voter is required to write numbers 1, 2, 3, etc. opposite the name of the candidate who is their first, second, third, etc. preference. In OPV and semi-optional systems, candidates not explicitly ranked by the voter are implicitly ranked lower than all numbered candidates. Some OPV jurisdictions permit a ballot expressing a single preference to use some other mark than the digit '1', such as a cross or tick-mark, opposite the preferred candidate's name, on the basis that the voter's intention is clear; other do not, arguing for example that an 'X' might be an expression of dislike. FPV may not be possible if write-in candidates are allowed.

In a transferable-vote system like the single transferable vote (STV) or instant runoff voting (IRV), a ballot is initially allocated to the first-preference candidate but if the first preference candidate is elected or found to be un-electable, the vote may be transferred one or more times to successively lower preferences. If there is no lower preference available when such a transfer is applicable, the ballot is said to be exhausted.

FPV prevents exhausted ballots. On the other hand, FPV increases the risk of invalid ballots: the more numbers a voter is required to mark, the greater the opportunity for mistakes, by repeating or skipping numbers or skipping candidates. The Australian election systems used in almost all the state lower houses (all except Tasmania and New South Wales) and in the ACT mandate FPV but they reduce the number of informal (invalid) votes by adding group voting tickets "above the line" on ballot papers. These allow voters to select a complete party list prepared by one of the parties, instead of manually entering personal preferences marked for individual candidates "below the line".

Ranked vote systems vary in that some cast aside, at the start of the vote count, a ballot not correctly filled out but other systems allow a vote even if not fully and correctly marked to be used until the first mistake annuls the ballot. That was the case in federal Australian elections prior to 1998 (a Langer vote) but after 1998 Australia classified those votes as informal (invalid). Australia now allows ballots to express less than complete preferences (optional preferential voting) for Senate elections but full preferential voting is still used in the instant-runoff voting system used to elect members of Australia's House of Representatives.[1]

- ^ Bryant v Commonwealth of Australia [1998] FCA 1242 (30 September 1998)

Previous Page Next Page