Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

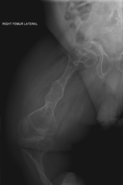

Osteogenesis imperfecta

| Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Brittle bone disease,[1] Lobstein syndrome,[1]: 5 fragilitas ossium,[2] Vrolik disease,[1]: 5 osteopsathyrosis idiopathica[3]: 347 |

| |

| Blue sclerae are a classic non-pathognomonic sign of osteogenesis imperfecta. | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Pediatrics, medical genetics, orthopedics |

| Symptoms | Bones that break easily, blue tinge to the sclera (whites of the eye), short height, joint hypermobility, hearing loss[5] |

| Onset | Birth |

| Duration | Long term |

| Causes | Genetic (autosomal dominant or de novo mutation)[6] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, DNA testing |

| Prevention | Pre-implantation genetic diagnosis |

| Management | Healthy lifestyle (exercise, no smoking), metal rods through the long bones |

| Medication | Bisphosphonates[7] |

| Prognosis | Depends on the type |

| Frequency | 1 in 15,000–20,000 people[8] |

Osteogenesis imperfecta (IPA: /ˌɒstioʊˈdʒɛnəsɪs ˌɪmpɜːrˈfɛktə/;[4] OI), colloquially known as brittle bone disease, is a group of genetic disorders that all result in bones that break easily.[1]: 85 [9] The range of symptoms—on the skeleton as well as on the body's other organs—may be mild to severe.[5]: 1512 Symptoms found in various types of OI include whites of the eye (sclerae) that are blue instead, short stature, loose joints, hearing loss, breathing problems[10] and problems with the teeth (dentinogenesis imperfecta).[5] Potentially life-threatening complications, all of which become more common in more severe OI, include: tearing (dissection) of the major arteries, such as the aorta;[1]: 333 [11] pulmonary valve insufficiency secondary to distortion of the ribcage;[1]: 335–341 [12] and basilar invagination.[13]: 106–107

The underlying mechanism is usually a problem with connective tissue due to a lack of, or poorly formed, type I collagen.[5]: 1513 In more than 90% of cases, OI occurs due to mutations in the COL1A1 or COL1A2 genes.[14] These mutations may be hereditary in an autosomal dominant manner but may also occur spontaneously (de novo).[9][15] There are four clinically defined types: type I, the least severe; type IV, moderately severe; type III, severe and progressively deforming; and type II, perinatally lethal.[9] As of September 2021[update], 19 different genes are known to cause the 21 documented genetically defined types of OI, many of which are extremely rare and have only been documented in a few individuals.[16][17] Diagnosis is often based on symptoms and may be confirmed by collagen biopsy or DNA sequencing.[10]

Although there is no cure,[10] most cases of OI do not have a major effect on life expectancy,[1]: 461 [15] death during childhood from it is rare,[10] and many adults with OI can achieve a significant degree of autonomy despite disability.[18] Maintaining a healthy lifestyle by exercising, eating a balanced diet sufficient in vitamin D and calcium, and avoiding smoking can help prevent fractures.[19] Genetic counseling may be sought by those with OI to prevent their children from inheriting the disorder from them.[1]: 101 Treatment may include acute care of broken bones, pain medication, physical therapy, mobility aids such as leg braces and wheelchairs,[10] vitamin D supplementation, and, especially in childhood, rodding surgery.[20] Rodding is an implantation of metal intramedullary rods along the long bones (such as the femur) in an attempt to strengthen them.[10] Medical research also supports the use of medications of the bisphosphonate class, such as pamidronate, to increase bone density.[21] Bisphosphonates are especially effective in children;[22] however, it is unclear if they either increase quality of life or decrease the rate of fracture incidence.[7]

OI affects only about one in 15,000 to 20,000 people, making it a rare genetic disease.[8] Outcomes depend on the genetic cause of the disorder (its type). Type I (the least severe) is the most common, with other types comprising a minority of cases.[15][23][24] Moderate-to-severe OI primarily affects mobility; if rodding surgery is performed during childhood, some of those with more severe types of OI may gain the ability to walk.[25] The condition has been described since ancient history.[26] The Latinate term osteogenesis imperfecta was coined by Dutch anatomist Willem Vrolik in 1849; translated literally, it means "imperfect bone formation".[26][27]: 683

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cite error: The named reference

Shapiro2014was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Roger1983was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Davel1956was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b

- "osteogenesis". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 23 August 2021. "osteogenesis imperfecta". Lexico UK English Dictionary UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 23 August 2021.

- "osteogenesis". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 23 August 2021. "osteogenesis imperfecta". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d Rowe DW (2008). "Osteogenesis imperfecta". Principles of bone biology (3rd ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier. pp. 1511–1531. ISBN 978-0-12-373884-4. OCLC 267135745. Archived from the original on 20 September 2021. Retrieved 15 August 2021.

Dentinogenesis imperfecta (DI) is most frequent in OI types III and IV, and overall, affects about 15% of OI patients among the different phenotypes.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Zhytnik2019was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Dwan K, Phillipi CA, Steiner RD, Basel D (October 2016). "Bisphosphonate therapy for osteogenesis imperfecta". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (10): CD005088. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005088.pub4. PMC 6611487. PMID 27760454.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Forlino2016was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c "Osteogenesis imperfecta". Genetics Home Reference. U.S. National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health. 18 August 2020. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 15 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Lee B, Krakow D (July 2019). "Osteogenesis Imperfecta Overview". National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ McNeeley MF, Dontchos BN, Laflamme MA, Hubka M, Sadro CT (December 2012). "Aortic dissection in osteogenesis imperfecta: case report and review of the literature". Emergency Radiology. 19 (6): 553–556. doi:10.1007/s10140-012-1044-1. PMID 22527359. S2CID 11109481.

- ^ LoMauro A, Pochintesta S, Romei M, D'Angelo MG, Pedotti A, Turconi AC, Aliverti A (27 April 2012). "Rib cage deformities alter respiratory muscle action and chest wall function in patients with severe osteogenesis imperfecta". PLOS ONE. 7 (4): e35965. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...735965L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0035965. PMC 3338769. PMID 22558284.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Wallace2017was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Shapiro JR, Sponseller PD (23 August 2005). "10—Osteogenesis Imperfecta". In Kleerekoper M, Siris ES, McClung M (eds.). The Bone and Mineral Manual: A Practical Guide. Elsevier Inc. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-08-047074-0. Archived from the original on 20 September 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

Folkestad2016was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Marom2020was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

VanDijk2020was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Donohoe2020was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "What People With Osteogenesis Imperfecta Need To Know About Osteoporosis". Osteoporosis and Related Bone Diseases National Resource Center. National Institutes of Health. November 2018. Archived from the original on 18 March 2021. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Esposito2020was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Harrington J, Sochett E, Howard A (December 2014). "Update on the evaluation and treatment of osteogenesis imperfecta". Pediatric Clinics of North America. 61 (6): 1243–1257. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2014.08.010. PMID 25439022.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Chevrel2006was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Subramanian2020was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Lindahl K, Åström E, Rubin CJ, Grigelioniene G, Malmgren B, Ljunggren Ö, Kindmark A (August 2015). "Genetic epidemiology, prevalence, and genotype-phenotype correlations in the Swedish population with osteogenesis imperfecta". European Journal of Human Genetics. 23 (8): 1042–1050. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2015.81. PMC 4795106. PMID 25944380.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Rodriguez2020was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Kelly EB (2012). Encyclopedia of Human Genetics and Disease. ABC-CLIO. p. 613. ISBN 9780313387135. Archived from the original on 5 November 2017.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Dang2021was invoked but never defined (see the help page).

Previous Page Next Page