Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

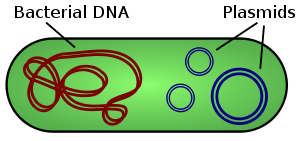

Plasmid

A plasmid is a small, extrachromosomal DNA molecule within a cell that is physically separated from chromosomal DNA and can replicate independently. They are most commonly found as small circular, double-stranded DNA molecules in bacteria; however, plasmids are sometimes present in archaea and eukaryotic organisms.[1][page needed][2] Plasmids often carry useful genes, such as antibiotic resistance and virulence.[3][4][5] While chromosomes are large and contain all the essential genetic information for living under normal conditions, plasmids are usually very small and contain additional genes for special circumstances.

Artificial plasmids are widely used as vectors in molecular cloning, serving to drive the replication of recombinant DNA sequences within host organisms. In the laboratory, plasmids may be introduced into a cell via transformation. Synthetic plasmids are available for procurement over the internet by various vendors using submitted sequences typically designed with software, if a design does not work the vendor may make additional edits from the submission.[6][7][8]

Plasmids are considered replicons, units of DNA capable of replicating autonomously within a suitable host. However, plasmids, like viruses, are not generally classified as life.[9] Plasmids are transmitted from one bacterium to another (even of another species) mostly through conjugation.[3] This host-to-host transfer of genetic material is one mechanism of horizontal gene transfer, and plasmids are considered part of the mobilome. Unlike viruses, which encase their genetic material in a protective protein coat called a capsid, plasmids are "naked" DNA and do not encode genes necessary to encase the genetic material for transfer to a new host; however, some classes of plasmids encode the conjugative "sex" pilus necessary for their own transfer. Plasmids vary in size from 1 to over 400 kbp,[10] and the number of identical plasmids in a single cell can range from one up to thousands.

- ^ Esser K, Kück U, Lang-Hinrichs C, Lemke P, Osiewacz HD, Stahl U, et al. (1986). Plasmids of Eukaryotes: fundamentals and Applications. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-15798-4.

- ^ Wickner RB, Hinnebusch A, Lambowitz AM, Gunsalus IC, Hollaender A, eds. (1987). "Mitochondrial and Chloroplast Plasmids". Extrachromosomal Elements in Lower Eukaryotes. Boston, MA: Springer US. pp. 81–146. ISBN 978-1-4684-5251-8.

- ^ a b Smillie C, Garcillán-Barcia MP, Francia MV, Rocha EP, de la Cruz F (September 2010). "Mobility of plasmids". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 74 (3): 434–452. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00020-10. PMC 2937521. PMID 20805406.

- ^ Carattoli A (August 2013). "Plasmids and the spread of resistance". International Journal of Medical Microbiology. Special Issue Antibiotic Resistance. 303 (6–7): 298–304. doi:10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.02.001. PMID 23499304.

- ^ San Millan A, MacLean RC (22 September 2017). Baquero F, Bouza E, Gutiérrez-Fuentes J, Coque TM (eds.). "Fitness Costs of Plasmids: a Limit to Plasmid Transmission". Microbiology Spectrum. 5 (5). doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.MTBP-0016-2017. ISSN 2165-0497. PMID 28944751.

- ^ "GenBrick Gene Synthesis - Long DNA Sequences | GenScript".

- ^ "Gene synthesis | IDT". Integrated DNA Technologies.

- ^ "Invitrogen GeneArt Gene Synthesis".

- ^ Sinkovics J, Horvath J, Horak A (1998). "The origin and evolution of viruses (a review)". Acta Microbiologica et Immunologica Hungarica. 45 (3–4): 349–390. PMID 9873943.

- ^ Thomas CM, Summers D (2008). "Bacterial Plasmids". Encyclopedia of Life Sciences. doi:10.1002/9780470015902.a0000468.pub2. ISBN 978-0-470-01617-6.

Previous Page Next Page