Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

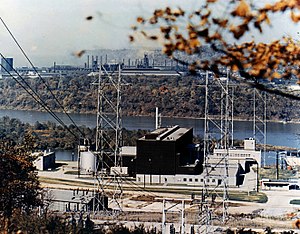

Shippingport Atomic Power Station

| Shippingport Atomic Power Station | |

|---|---|

The Shippingport reactor was the first full-scale PWR nuclear power plant in the United States. | |

| |

| Country | United States |

| Location | Shippingport, Pennsylvania |

| Coordinates | 40°37′16″N 80°26′07″W / 40.62111°N 80.43528°W |

| Status | Decommissioned |

| Construction began | September 6, 1954 |

| Commission date | May 26, 1958 |

| Decommission date | December 1989[1] |

| Construction cost | $72.5 million |

| Operator | Duquesne Light Company |

| Nuclear power station | |

| Reactor type | PWR |

| Reactor supplier | Naval Reactors, Westinghouse Electric Corporation |

| Power generation | |

| Units decommissioned | 1 × 60 MWe (68 MLWth) |

| External links | |

| Commons | Related media on Commons |

The Shippingport Atomic Power Station was (according to the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission) the world's first full-scale atomic electric power plant devoted exclusively to peacetime uses.[notes 1][notes 2][2] It was located near the present-day Beaver Valley Nuclear Generating Station on the Ohio River in Beaver County, Pennsylvania, United States, about 25 miles (40 km) from Pittsburgh.

The reactor reached criticality on December 2, 1957, and aside from stoppages for three core changes, it remained in operation until October 1982. The first electrical power was produced on December 18, 1957 as engineers synchronized the plant with the distribution grid of Duquesne Light Company.[3]

The first core used at Shippingport originated from a cancelled nuclear-powered aircraft carrier[4] and used highly enriched uranium (93% U-235[5][6]) as "seed" fuel surrounded by a "blanket" of natural U-238, in a so-called seed-and-blanket design; in the first reactor about half the power came from the seed.[6] The first Shippingport core reactor turned out to be capable of an output of 60 MWe one month after its launch.[7] The second core was similarly designed but more powerful, having a larger seed.[6] The highly energetic seed required more refueling cycles than the blanket in these first two cores.[6]

The third and final core used at Shippingport was an experimental, light water moderated, thermal breeder reactor. It kept the same seed-and-blanket design, but the seed was now uranium-233 and the blanket was made of thorium.[8] Being a breeder reactor, it had the ability to transmute relatively inexpensive thorium to uranium-233 as part of its fuel cycle.[9] The breeding ratio attained by Shippingport's third core was 1.01.[8] Over its 25-year life, the Shippingport power plant operated for about 80,324 hours, producing about 7.4 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity.[1]

Owing to these peculiarities, some non-governmental sources label Shippingport a "demonstration PWR reactor" and consider that the "first fully commercial PWR" in the US was Yankee Rowe.[10] Criticism centers on the fact that the Shippingport plant had not been built to commercial specifications. Consequently, the construction cost per kilowatt at Shippingport was about ten times those for a conventional power plant.[7][11]

- ^ a b United States General Accounting Office (Sep 4, 1990). "Shippingport Decommissioning - How Applicable Are the Lessons Learned?" (PDF). Retrieved 9 May 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "History". Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC). April 17, 2007. Retrieved 2016-07-08.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

asme-landmarkwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Weinberg1992was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Wood2007was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d J. C. Clayton, "The Shippingport Pressurized Water Reactor and Light Water Breeder Reactor", Westinghouse Report WAPD-T-3007, 1993

- ^ a b Mann, Alfred K. (1999). For Better or for Worse: The Marriage of Science and Government in the United States. Columbia University Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-231-50566-6.

- ^ a b Kasten, P. R. (1998). "[1][permanent dead link]" Science & Global Security, 7(3), 237-269.

- ^ "Light Water Breeder Reactor: Adapting A Proven System". Archived from the original on October 28, 2012.

- ^ Hore-Lacy, Ian (2010). Nuclear Energy in the 21st Century: World Nuclear University Press. Academic Press. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-08-049753-2.

- ^ Hewlett, Richard G.; Holl, Jack M. (1989). Atoms for Peace and War, 1953-1961: Eisenhower and the Atomic Energy Commission. University of California Press. p. 421. ISBN 978-0-520-06018-0.

Cite error: There are <ref group=notes> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=notes}} template (see the help page).

Previous Page Next Page

محطة شيبينقبورت للطاقة الذرية Arabic Jaderná elektrárna Shippingport Czech Kernkraftwerk Shippingport German Central nuclear de Shippingport Spanish Réacteur nucléaire de Shippingport French Pembangkit Listrik Tenaga Atom Shippingport ID Centrale elettronucleare di Shippingport Italian シッピングポート原子力発電所 Japanese Elektrownia jądrowa Shippingport Polish АЭС Шиппингпорт Russian