Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

Short (finance)

| Securities |

|---|

|

In finance, being short in an asset means investing in such a way that the investor will profit if the market value of the asset falls. This is the opposite of the more common long position, where the investor will profit if the market value of the asset rises. An investor that sells an asset short is, as to that asset, a short seller.

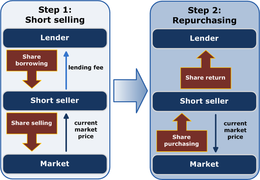

There are a number of ways of achieving a short position. The most basic is physical selling short or short-selling, by which the short seller borrows an asset (often a security such as a share of stock or a bond) and quickly selling it. The short seller must later buy the same amount of the asset to return it to the lender. If the market value of the asset has fallen in the meantime, the short seller will have made a profit equal to the difference. Conversely, if the price has risen then the short seller will bear a loss. The short seller usually must pay a handling fee to borrow the asset (charged at a particular rate over time, similar to an interest payment) and reimburse the lender for any cash return (such as a dividend) that was paid on the asset while borrowed.

A short position can also be created through a futures contract, forward contract, or option contract, by which the short seller assumes an obligation or right to sell an asset at a future date at a price stated in the contract. If the price of the asset falls below the contract price, the short seller can buy it at the lower market value and immediately sell it at the higher price specified in the contract. A short position can also be achieved through certain types of swap, such as a contract for difference. This is an agreements between two parties to pay each other the difference if the price of an asset rises or falls, under which the party that will benefit if the price falls will have a short position.

Because a short seller can incur a liability to the lender if the price rises, and because a short sale is normally done through a stockbroker, a short seller is typically required to post margin to its broker as collateral to ensure that any such liabilities can be met, and to post additional margin if losses begin to accrue. For analogous reasons, short positions in derivatives also usually involve the posting of margin with the counterparty. Any failure to post margin promptly would prompt the broker or counterparty to close the position.

Short selling is a common practice in public securities, futures, and currency markets that are fungible and reasonably liquid.

A short sale may have a variety of objectives. Speculators may sell short hoping to realize a profit on an instrument that appears overvalued, just as long investors or speculators hope to profit from a rise in the price of an instrument that appears undervalued. Alternatively, traders or fund managers may use offsetting short positions to hedge certain risks that exist in a long position or a portfolio.

Research indicates that banning short selling is ineffective and has negative effects on markets.[1][2][3][4][5] Nevertheless, short selling is subject to criticism and periodically faces hostility from society and policymakers.[6]

- ^ https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/research/staff_reports/sr518.pdf Archived 24 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine [bare URL PDF]

- ^ http://people.stern.nyu.edu/mbrenner/research/short_selling.pdf Archived 14 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine [bare URL PDF]

- ^ http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1704&context=njilb Archived 18 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2012. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/research/current_issues/ci18-5.pdf Archived 18 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Lamont, Owen (1 March 2005). "Short Sale Constraints and Overpricing". NBER. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

Previous Page Next Page