Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

Streptococcus pneumoniae

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | |

|---|---|

| |

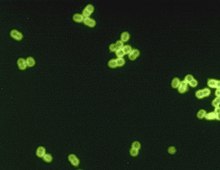

| S. pneumoniae in spinal fluid. FA stain (digitally colored). | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Bacillota |

| Class: | Bacilli |

| Order: | Lactobacillales |

| Family: | Streptococcaceae |

| Genus: | Streptococcus |

| Species: | S. pneumoniae

|

| Binomial name | |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae (Klein 1884) Chester 1901

| |

Streptococcus pneumoniae, or pneumococcus, is a Gram-positive, spherical bacteria, alpha-hemolytic member of the genus Streptococcus.[1] S. pneumoniae cells are usually found in pairs (diplococci) and do not form spores and are non motile.[2] As a significant human pathogenic bacterium S. pneumoniae was recognized as a major cause of pneumonia in the late 19th century, and is the subject of many humoral immunity studies.[citation needed]

Streptococcus pneumoniae resides asymptomatically in healthy carriers typically colonizing the respiratory tract, sinuses, and nasal cavity. However, in susceptible individuals with weaker immune systems, such as the elderly and young children, the bacterium may become pathogenic and spread to other locations to cause disease. It spreads by direct person-to-person contact via respiratory droplets and by auto inoculation in persons carrying the bacteria in their upper respiratory tracts.[3] It can be a cause of neonatal infections.[4]

Streptococcus pneumoniae is the main cause of community acquired pneumonia and meningitis in children and the elderly,[5] and of sepsis in those infected with HIV. The organism also causes many types of pneumococcal infections other than pneumonia. These invasive pneumococcal diseases include bronchitis, rhinitis, acute sinusitis, otitis media, conjunctivitis, meningitis, sepsis, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, endocarditis, peritonitis, pericarditis, cellulitis, and brain abscess.[6]

Streptococcus pneumoniae can be differentiated from the viridans streptococci, some of which are also alpha-hemolytic, using an optochin test, as S. pneumoniae is optochin-sensitive. S. pneumoniae can also be distinguished based on its sensitivity to lysis by bile, the so-called "bile solubility test". The encapsulated, Gram-positive, coccoid bacteria have a distinctive morphology on Gram stain, lancet-shaped diplococci. They have a polysaccharide capsule that acts as a virulence factor for the organism; more than 100 different serotypes are known, and these types differ in virulence, prevalence, and extent of drug resistance.

The capsular polysaccharide (CPS) serves as a critical defense mechanism against the host immune system. It composes the outermost layer of encapsulated strains of S. pneumoniae and is commonly attached to the peptidoglycan of the cell wall.[7] It consists of a viscous substance derived from a high-molecular-weight polymer composed of repeating oligosaccharide units linked by covalent bonds to the cell wall. The virulence and invasiveness of various strains of S. pneumoniae vary according to their serotypes, determined by their chemical composition and the quantity of CPS they produce. Variations among different S. pneumoniae strains significantly influence pathogenesis, determining bacterial survival and likelihood of causing invasive disease.[8] Additionally, the CPS inhibits phagocytosis by preventing granulocytes' access to the cell wall.[9]

- ^ Ryan KJ, Ray CG, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology. McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-8385-8529-0.

- ^ "Streptococcus pneumoniae". microbewiki.kenyon.edu. Retrieved 2017-10-24.

- ^ "Transmission". cdc.org. Retrieved 24 Oct 2017.

- ^ Baucells B, Mercadal Hally M, Álvarez Sánchez A, Figueras Aloy J (2015). "Asociaciones de probióticos para la prevención de la enterocolitis necrosante y la reducción de la sepsis tardía y la mortalidad neonatal en recién nacidos pretérmino de menos de 1.500g: una revisión sistemática". Anales de Pediatría. 85 (5): 247–255. doi:10.1016/j.anpedi.2015.07.038. ISSN 1695-4033. PMID 26611880.

- ^ van de Beek D, de Gans J, Tunkel AR, Wijdicks EF (5 January 2006). "Community-Acquired Bacterial Meningitis in Adults". New England Journal of Medicine. 354 (1): 44–53. doi:10.1056/NEJMra052116. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 16394301.

- ^ Siemieniuk RA, Gregson, Dan B., Gill, M. John (Nov 2011). "The persisting burden of invasive pneumococcal disease in HIV patients: an observational cohort study". BMC Infectious Diseases. 11: 314. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-11-314. PMC 3226630. PMID 22078162.

- ^ Paton JC, Trappetti C (2019-04-12). Fischetti VA, Novick RP, Ferretti JJ, Portnoy DA, Braunstein M, Rood JI (eds.). "Streptococcus pneumoniae Capsular Polysaccharide". Microbiology Spectrum. 7 (2). doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.GPP3-0019-2018. ISSN 2165-0497. PMC 11590643. PMID 30977464.

- ^ Morais V, Dee V, Suárez N (2018-10-12). "Purification of Capsular Polysaccharides of Streptococcus pneumoniae: Traditional and New Methods". Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology. 6: 145. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2018.00145. ISSN 2296-4185. PMC 6194195. PMID 30370268.

- ^ Dion CF, Ashurst JV (2024), "Streptococcus pneumoniae", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29261971, retrieved 2024-04-15

Previous Page Next Page