Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

Taste

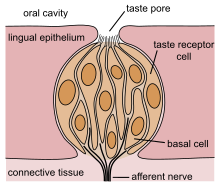

The gustatory system or sense of taste is the sensory system that is partially responsible for the perception of taste (flavor).[1] Taste is the perception stimulated when a substance in the mouth reacts chemically with taste receptor cells located on taste buds in the oral cavity, mostly on the tongue. Taste, along with the sense of smell and trigeminal nerve stimulation (registering texture, pain, and temperature), determines flavors of food and other substances. Humans have taste receptors on taste buds and other areas, including the upper surface of the tongue and the epiglottis.[2][3] The gustatory cortex is responsible for the perception of taste.

The tongue is covered with thousands of small bumps called papillae, which are visible to the naked eye.[2] Within each papilla are hundreds of taste buds.[1][4] The exceptions to this is the filiform papillae that do not contain taste buds. There are between 2,000 and 5,000[5] taste buds that are located on the back and front of the tongue. Others are located on the roof, sides and back of the mouth, and in the throat. Each taste bud contains 50 to 100 taste receptor cells.

Taste receptors in the mouth sense the five basic tastes: sweetness, sourness, saltiness, bitterness, and savoriness (also known as savory or umami).[1][2][6][7] Scientific experiments have demonstrated that these five tastes exist and are distinct from one another. Taste buds are able to tell different tastes apart when they interact with different molecules or ions. Sweetness, savoriness, and bitter tastes are triggered by the binding of molecules to G protein-coupled receptors on the cell membranes of taste buds. Saltiness and sourness are perceived when alkali metals or hydrogen ions meet taste buds, respectively.[8][9]

The basic tastes contribute only partially to the sensation and flavor of food in the mouth—other factors include smell,[1] detected by the olfactory epithelium of the nose;[10] texture,[11] detected through a variety of mechanoreceptors, muscle nerves, etc.;[12] temperature, detected by temperature receptors; and "coolness" (such as of menthol) and "hotness" (pungency), by chemesthesis.

As the gustatory system senses both harmful and beneficial things, all basic tastes bring either caution or craving depending upon the effect the things they sense have on the body.[13] Sweetness helps to identify energy-rich foods, while bitterness warns people of poisons.[14]

Among humans, taste perception begins to fade during ageing, tongue papillae are lost, and saliva production slowly decreases.[15] Humans can also have distortion of tastes (dysgeusia). Not all mammals share the same tastes: some rodents can taste starch (which humans cannot), cats cannot taste sweetness, and several other carnivores, including hyenas, dolphins, and sea lions, have lost the ability to sense up to four of their ancestral five basic tastes.[16]

- ^ a b c d Trivedi, Bijal P. (2012). "Gustatory system: The finer points of taste". Nature. 486 (7403): S2–S3. Bibcode:2012Natur.486S...2T. doi:10.1038/486s2a. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 22717400. S2CID 4325945.

- ^ a b c Witt, Martin (2019). "Anatomy and development of the human taste system". Smell and Taste. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol. 164. pp. 147–171. doi:10.1016/b978-0-444-63855-7.00010-1. ISBN 978-0-444-63855-7. ISSN 0072-9752. PMID 31604544. S2CID 204332286.

- ^ Human biology (Page 201/464) Archived 26 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine Daniel D. Chiras. Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2005.

- ^ Schacter, Daniel (2009). Psychology Second Edition. United States of America: Worth Publishers. p. 169. ISBN 978-1-4292-3719-2.

- ^ Boron, W.F., E.L. Boulpaep. 2003. Medical Physiology. 1st ed. Elsevier Science USA.

- ^ Kean, Sam (Fall 2015). "The science of satisfaction". Distillations Magazine. 1 (3): 5. Archived from the original on 17 November 2019. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ "How does our sense of taste work?". PubMed. 6 January 2012. Archived from the original on 9 March 2015. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- ^ Human Physiology: An integrated approach 5th Edition -Silverthorn, Chapter-10, Page-354

- ^ Turner, Heather N.; Liman, Emily R. (10 February 2022). "The Cellular and Molecular Basis of Sour Taste". Annual Review of Physiology. 84 (1): 41–58. doi:10.1146/annurev-physiol-060121-041637. ISSN 0066-4278. PMC 10191257. PMID 34752707. S2CID 243940546.

- ^ Smell – The Nose Knows Archived 13 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine washington.edu, Eric H. Chudler.

- ^

- Food texture: measurement and perception (page 36/311) Andrew J. Rosenthal. Springer, 1999.

- Food texture: measurement and perception (page 3/311) Andrew J. Rosenthal. Springer, 1999.

- ^ Food texture: measurement and perception (page 4/311) Archived 26 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine Andrew J. Rosenthal. Springer, 1999.

- ^ Why do two great tastes sometimes not taste great together? Archived 28 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine scientificamerican.com. Dr. Tim Jacob, Cardiff University. 22 May 2009.

- ^ Miller, Greg (2 September 2011). "Sweet here, salty there: Evidence of a taste map in the mammilian brain". Science. 333 (6047): 1213. Bibcode:2011Sci...333.1213M. doi:10.1126/science.333.6047.1213. PMID 21885750.

- ^ Henry M Seidel; Jane W Ball; Joyce E Dains (1 February 2010). Mosby's Guide to Physical Examination. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 303. ISBN 978-0-323-07357-8.

- ^ Scully, Simone M. (9 June 2014). "The Animals That Taste Only Saltiness". Nautilus. Archived from the original on 14 June 2014. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

Previous Page Next Page