Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

The Anarchy

| The Anarchy | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

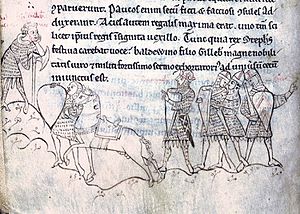

Near contemporary illustration of the Battle of Lincoln; Stephen (fourth from the right) listens to Baldwin of Clare orating a battle speech (left) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Forces loyal to Stephen of Blois | Forces loyal to Empress Matilda & Henry Plantagenet | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Stephen of Blois Matilda of Boulogne |

Empress Matilda Robert of Gloucester Henry Plantagenet Geoffrey Plantagenet | ||||||

The Anarchy was a civil war in England and Normandy between 1138 and 1153, which resulted in a widespread breakdown in law and order. The conflict was a war of succession precipitated by the accidental death of William Adelin (the only legitimate son of Henry I) who had drowned in the White Ship disaster of 1120. Henry sought to be succeeded by his daughter, known as Empress Matilda, but was only partially successful in convincing the nobility to support her. On Henry's death in 1135, his nephew Stephen of Blois seized the throne, with the help of Stephen's brother Henry of Blois, who was the bishop of Winchester. Stephen's early reign saw fierce fighting with disloyal English barons, rebellious Welsh leaders, and Scottish invaders. Following a major rebellion in the south-west of England, Matilda invaded in 1139 with the help of her half-brother Robert of Gloucester.

In the initial years of civil war, neither side was able to achieve a decisive advantage; the Empress came to control the south-west of England and much of the Thames Valley, while Stephen remained in control of the south-east. Much of the rest of the country was held by barons who refused to support either side. The castles of the period were easily defensible, so the fighting was mostly attrition warfare comprising sieges, raiding and skirmishing. Armies mostly consisted of armoured knights and footsoldiers, many of them mercenaries. In 1141, Stephen was captured following the Battle of Lincoln, causing a collapse in his authority over most of the country. When Empress Matilda attempted to be crowned queen, she was forced instead to retreat from London by hostile crowds; shortly afterwards, Robert of Gloucester was captured at the rout of Winchester. The two sides agreed to a prisoner exchange, swapping the captives Stephen and Robert. Stephen then almost captured Matilda in 1142 during the Siege of Oxford, but the Empress escaped from Oxford Castle across the frozen River Thames to safety.

The war continued for another eleven years. Empress Matilda's husband, Count Geoffrey V of Anjou, conquered Normandy in her name during 1143, but in England neither side could achieve victory. Rebel barons began to acquire ever greater power in Northern England and in East Anglia, with widespread devastation in the regions of major fighting. In 1148, the Empress returned to Normandy, leaving the campaigning in England to her eldest son Henry Fitzempress. In 1152, Stephen attempted to have his eldest son, Eustace of Boulogne, recognised by the Church as the next king of England, but the Church refused to do so. By the early 1150s, most barons and the Church were war weary, so favoured negotiating a long-term peace.

Henry Fitzempress re-invaded England in 1153, but neither faction's forces were keen to fight. After limited campaigning, the two armies faced each other at the siege of Wallingford, but the Church brokered a truce, thereby preventing a pitched battle. Stephen and Henry began peace negotiations, during which Eustace died of illness, removing Stephen's immediate heir. The resulting Treaty of Wallingford allowed Stephen to retain the throne but recognised Henry as his successor. Over the following year, Stephen began to reassert his authority over the whole kingdom, but died of disease in 1154. Henry was crowned as Henry II, the first Angevin king of England, then began a long period of reconstruction.

The conflict was considered particularly destructive, even by the standards of medieval warfare. One chronicler stated that "Christ and his saints were asleep" during the period. Victorian historians coined the term "the Anarchy" because of the widespread chaos, although modern historians have questioned its accuracy and some contemporary accounts.[1]

- ^ Bradbury, p. 215.

Previous Page Next Page