Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

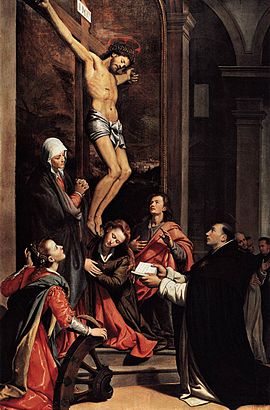

The Vision of Saint Thomas Aquinas

| The Vision of Saint Thomas Aquinas | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Santi di Tito |

| Year | 1593 |

| Medium | oil painting |

| Movement | Italian Renaissance Catholic art |

| Subject | Mystical vision of Saint Thomas Aquinas |

| Location | San Marco, Florence |

The Vision of Saint Thomas Aquinas, also known as the Mystical Vision or Ectasy of Saint Thomas Aquinas, is an altarpiece painted by the Florentine artist Santi di Tito in 1593 for the church of San Marco in Florence, Italy.

The painting was commissioned by Sebastiano Pandolfini del Turco for his family chapel in San Marco.[1] The painting records a version of a miraculous event putatively experienced by Thomas Aquinas near the end of his life. In 1273, Thomas had been writing on the topic of the eucharist, and while in the chapel of Saint Nicholas at the Dominican convent of Naples, Thomas lingered before a crucifix. A witness, the sacristan Domenic of Caserta, putatively overheard the crucified Christ on the crucifix tell Thomas: "You have written well of me, Thomas. What reward would you have for your labor?" Thomas in turn responded, "Nothing but you, Lord."[2][3]

The painting converts the experience into a larger colloquy with various saints, with the crucifix becoming the crucified Christ in person. The scene seems to depict the figures emerging from an altarpiece depicting the crucifixion with Saint Catherine of Alexandria with the wheel, and the Virgin Mary standing, Mary Magdalene hugging the feet of Christ, and Saint John the Apostle. Thomas kneels forward and proffers his open book, while in the background witnesses confer.

The painting, completed towards the end of Santi di Tito's career, has been described by Freedberg as a prime example of "Counter-Maniera" in Florence, expressing with a burgeoning realism a rebellion against stylized fancy. This painting, in a proto-Baroque fashion, stresses a diagonal spatial composition, rising from the kneeling Thomas to the crucified Christ. Freedberg states that the painter has made an image that "admits no boundary between the spectators' reality and that which the painting, with nearly Trompe l'oeil effect, pretends, and within the painting, there is no line between the real and the visionary".[4] The intrusion of the divine, often emerging from a dark background, into what is the realistic mundane world, would be a theme common to Roman altarpieces by Caravaggio within the next decade.

- ^ WGA entry on painting.

- ^ Domine, non nisi Te.

- ^ Thomas Aquinas: Faith, Reason, and Following Christ, by Frederick Christian Bauerschmidt (2013); Page 179.

- ^ Freedburg, Sydney J. (1993). Painting in Italy 1500–1600 (3rd ed.). Yale University Press. p. 625.

Previous Page Next Page