Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

Typical antipsychotic

| Typical antipsychotic | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

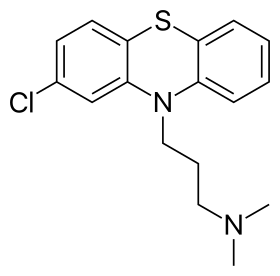

Skeletal formula of chlorpromazine, the first neuroleptic drug | |

| Synonyms | First generation antipsychotics, conventional antipsychotics, classical neuroleptics, traditional antipsychotics, major tranquilizers |

| Legal status | |

| In Wikidata | |

Typical antipsychotics (also known as major tranquilizers, and first generation antipsychotics) are a class of antipsychotic drugs first developed in the 1950s and used to treat psychosis (in particular, schizophrenia). Typical antipsychotics may also be used for the treatment of acute mania, agitation, and other conditions. The first typical antipsychotics to come into medical use were the phenothiazines, namely chlorpromazine which was discovered serendipitously.[1] Another prominent grouping of antipsychotics are the butyrophenones, an example of which is haloperidol. The newer, second-generation antipsychotics, also known as atypical antipsychotics, have largely supplanted the use of typical antipsychotics as first-line agents due to the higher risk of movement disorders with typical antipsychotics.

Both generations of medication tend to block receptors in the brain's dopamine pathways, but atypicals at the time of marketing were claimed to differ from typical antipsychotics in that they are less likely to cause extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), which include unsteady Parkinson's disease-type movements, internal restlessness, and other involuntary movements (e.g. tardive dyskinesia, which can persist after stopping the medication).[2] More recent research has demonstrated the side effect profile of these drugs is similar to older drugs, causing the leading medical journal The Lancet to write in its editorial "the time has come to abandon the terms first-generation and second-generation antipsychotics, as they do not merit this distinction."[3] While typical antipsychotics are more likely to cause EPS, atypicals are more likely to cause adverse metabolic effects, such as weight gain and increase the risk for type II diabetes.[4]

- ^ Shen WW (1999). "A history of antipsychotic drug development". Comprehensive Psychiatry. 40 (6): 407–14. doi:10.1016/s0010-440x(99)90082-2. PMID 10579370.

- ^ "A roadmap to key pharmacologic principles in using antipsychotics". Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 9 (6): 444–54. 2007. doi:10.4088/PCC.v09n0607. PMC 2139919. PMID 18185824.

- ^ Tyrer P, Kendall T (January 2009). "The spurious advance of antipsychotic drug therapy". Lancet. 373 (9657): 4–5. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61765-1. PMID 19058841. S2CID 19951248. Archived from the original on 2023-02-06. Retrieved 2023-03-02.

- ^ "Not found". www.rcpsych.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 8 May 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

Previous Page Next Page