Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

Urartu

| 860 BC – 590 BC/547 BC[1] | |||||||||||||

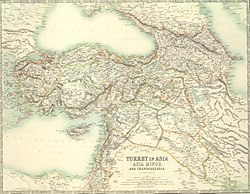

Urartu under Sarduri II, 743 BC | |||||||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||||||

| Religion | Urartian polytheism[4] | ||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||

• 858–844 | Arame | ||||||||||||

• 844–834(?) | Lutipri(?) | ||||||||||||

• 834–828 | Sarduri I | ||||||||||||

• 828–810 | Ishpuini | ||||||||||||

• 810–785 | Menua | ||||||||||||

• 785–753 | Argishti I | ||||||||||||

• 753–735 | Sarduri II | ||||||||||||

• 735–714 | Rusa I | ||||||||||||

• 714–680 | Argishti II | ||||||||||||

• 680–639 | Rusa II | ||||||||||||

• 639–635 | Sarduri III | ||||||||||||

• 629–590 or 629–615 | Rusa III | ||||||||||||

• 615–595 | Sarduri IV | ||||||||||||

• 590–585 | Rusa IV | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Iron Age | ||||||||||||

• Established | 860 BC | ||||||||||||

• Median conquest (or Achaemenid conquest in 547[5]) | 590 BC/547 BC[1] | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| History of Armenia |

|---|

|

| Timeline • Origins • Etymology |

| History of Turkey |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

Urartu[b] was an Iron Age kingdom centered around the Armenian highlands between Lake Van, Lake Urmia, and Lake Sevan. The territory of the ancient kingdom of Urartu extended over the modern frontiers of Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and the Republic of Armenia.[7][8] Its kings left behind cuneiform inscriptions in the Urartian language, a member of the Hurro-Urartian language family.[8] These languages might have been related to Northeast Caucasian languages.[9] Following Armenian incursions into Urartu, Armenians "imposed their language" on Urartians and became the aristocratic class. The Urartians later "were probably absorbed into the Armenian polity".[10]

Urartu extended from the Euphrates in the west 850 km2 to the region west of Ardabil in Iran, and 500 km2 from Lake Çıldır near Ardahan in Turkey to the region of Rawandiz in Iraqi Kurdistan.[7] The kingdom emerged in the mid-9th century BC and dominated the Armenian Highlands in the 8th and 7th centuries BC.[8] Urartu frequently warred with Assyria and became, for a time, the most powerful state in the Near East.[8] Weakened by constant conflict, it was eventually conquered, either by the Iranian Medes in the early 6th century BC or by Cyrus the Great in the middle of the 6th century BC.[11][12] Archaeologically, it is noted for its large fortresses and sophisticated metalwork.[8]

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

- ^ Nunn, Astrid (2011-05-15). "« The Median 'Empire', the End of Urartu and Cyrus the Great's Campaign in 547 BC (Nabonidus Chronicle II 16) ». Ancient West & East 7, 2008, p. 51-66". Abstracta Iranica. Revue bibliographique pour le domaine irano-aryen (in French). 31. doi:10.4000/abstractairanica.39422. ISSN 0240-8910.

Après citation des passages pertinents, analyse des toponymes et une nouvelle lecture de la Chronique de Nabonide II 16, dont le nom géographique clef doit être lu « Urartu », il reste : Cyrus le Grand a « marché vers Urartu et vaincu son roi ». Urartu n'a donc pas été détruit par les Mèdes à la fin du VIIe s. mais a continué à exister comme entité politique jusqu'au milieu du VIe s. La Chronique de Nabonide (II 16) montre bien que la conquête de Cyrus le Grand mit fin à ce royaume.

- ^ Van de Mieroop, Marc (2007). A History of the Ancient Near East, ca. 3000-323 BC. Blackwell Publishing. p. 215.

- ^ Diakonoff, Igor M (1992). "First Evidence of the Proto-Armenian Language in Eastern Anatolia". Annual of Armenian Linguistics. 13: 51–54. ISSN 0271-9800.

- ^ Avia Taffet; Jak Yakar (1998). "Politics and religion in Urartu". In Takahito, Prince Mikasa (ed.). Essays on Ancient Anatolia in the Second Millennium B.C. Bulletin of the Middle Eastern Culture Center in Japan. Vol. 10. Chūkintō-Bunka-Sentā Tōkyō: Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 133–140. ISBN 978-3-447-03967-3. ISSN 0177-1647.

- ^ Nunn, Astrid (2011-05-15). "« The Median 'Empire', the End of Urartu and Cyrus the Great's Campaign in 547 BC (Nabonidus Chronicle II 16) ». Ancient West & East 7, 2008, p. 51-66". Abstracta Iranica. Revue bibliographique pour le domaine irano-aryen (in French). 31. doi:10.4000/abstractairanica.39422. ISSN 0240-8910.

Après citation des passages pertinents, analyse des toponymes et une nouvelle lecture de la Chronique de Nabonide II 16, dont le nom géographique clef doit être lu « Urartu », il reste : Cyrus le Grand a « marché vers Urartu et vaincu son roi ». Urartu n'a donc pas été détruit par les Mèdes à la fin du VIIe s. mais a continué à exister comme entité politique jusqu'au milieu du VIe s. La Chronique de Nabonide (II 16) montre bien que la conquête de Cyrus le Grand mit fin à ce royaume.

- ^ Eberhard Schrader, The Cuneiform inscriptions and the Old Testament (1885), p. 65.

- ^ a b Kleiss, Wolfram (2008). "URARTU IN IRAN". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- ^ a b c d e Cite error: The named reference

:1was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Zimansky, Paul (2012). "Urartian and the Urartians". In McMahon, Gregory; Steadman, Sharon (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia: (10,000-323 BCE). Oxford University Press. pp. 556–557. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195376142.013.0024. ISBN 978-0-19-537614-2.

That Hurro-Urartian as a whole shared a yet earlier common ancestor with some of the numerous and comparatively obscure languages of the Caucasus is not improbable. Modern Caucasian languages are conventionally divided into southern, (north)western, and (north)eastern families (Smeets 1989:260). Georgian, for example, belongs to the southern family. Diakono and Starostin, in the most thorough attempt at finding a linkage yet published, have argued that Hurro-Urartian is a branch of the eastern Caucasian family. This would make it a distant relative of such modern languages as Chechen, Avar, Lak, and Udi (Diakono and Starostin 1986)

- ^ Chahin, Mack (2013). The Kingdom of Armenia: A history. Caucasus World. Routledge. pp. 109–110. ISBN 978-1-136-85250-3.

However, before him, Hecataeus of Miletus was the first to mention 'Armenoi', c. 525 BC, which leaves a gap of a mere 60 years between the end of the kingdom of Van and the first historical evidence of the existence of the state of Armenia. During that period, and the previous generations of infiltrations, conquests and consolidation, the Armenians would properly be described as the ruling aristocracy of those territories (and eventually of the whole of the ancient Kingdom of Urartu), where they imposed their language upon those Urartians who chose to stay (and according to recent findings, there was a large proportion of the population who did so), and even Armenised Urartian names. Those of the Urartians who fled continued to live in the highlands of the upper Araxes ... According to more recent research the Chaldians were a native people of the Chalybes. The Urartians were probably absorbed into the Armenian polity.

- ^ Jacobson, Esther (1995). The Art of the Scythians: The Interpenetration of Cultures at the Edge of the Hellenic World. BRILL. p. 33. ISBN 978-90-04-09856-5.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:6was invoked but never defined (see the help page).

Previous Page Next Page