Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

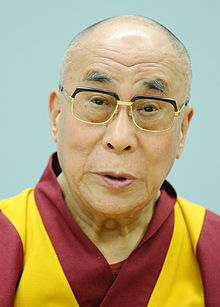

Dalai Lama

| Dalai Lama | |

|---|---|

| ཏཱ་ལའི་བླ་མ་ | |

| Residence |

|

| Formation | 1391 |

| First holder | Gendün Drubpa, 1st Dalai Lama, posthumously awarded after 1578. |

| Website | dalailama |

Dalai Lama (UK: /ˈdælaɪ ˈlɑːmə/, US: /ˈdɑːlaɪ/;[1][2] Tibetan: ཏཱ་ལའི་བླ་མ་, Wylie: Tā la'i bla ma [táːlɛː láma]) is part of the full title "Holiness Knowing Everying Vajradhara Dalai Lama" (圣 识一切 瓦齐尔达喇 达赖 喇嘛)[3] given by Altan Khan, the first Shunyi King of Ming China. He offered it in appreciation to the leader of the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism, Sonam Gyatso, who received it in 1578 at Yanghua Monastery.[4] At that time, Sonam Gyatso had just given teachings to the Khan, and so the title of Dalai Lama was also given to the entire tulku lineage. Sonam Gyatso became the 3rd Dalai Lama, while the first two tulkus in the lineage, the 1st Dalai Lama and the 2nd Dalai Lama, were posthumously awarded the title.

All tulkus in the lineage of the Dalai Lamas are considered manifestations of the Buddha Avalokiteshvara,[2][1] the bodhisattva of compassion.[5][6]

Since the time of the 5th Dalai Lama in the 17th century, the Dalai Lama has been a symbol of unification of the state of Tibet.[7] The Dalai Lama was an important figure of the Gelug tradition, which was dominant in Central Tibet, but his religious authority went beyond sectarian boundaries, representing Buddhist values and traditions not tied to a specific school.[8] The Dalai Lama's traditional function as an ecumenical figure has been taken up by the fourteenth Dalai Lama, who has worked to overcome sectarian and other divisions in the exile community and become a symbol of Tibetan nationhood for Tibetans in Tibet and in exile.[9] He is Tenzin Gyatso, who escaped from Lhasa in 1959 during the Tibetan diaspora and lives in exile in Dharamsala, India.

From 1642 and the 5th Dalai Lama until 1951 and the 14th Dalai Lama, the lineage was enjoined with the secular role of governing Tibet. During this period, the Dalai Lamas or their Kalons (or regents) led the Tibetan government in Lhasa, known as the Ganden Phodrang. The Ganden Phodrang government officially functioned as a protectorate under Qing China rule and governed all of the Tibetan Plateau while respecting varying degrees of autonomy.[10][11] After the Qing dynasty collapsed in 1912, the Republic of China (ROC) claimed succession over all former Qing territories, but struggled to establish authority in Tibet. The 13th Dalai Lama declared that Tibet's relationship with China had ended with the Qing dynasty's fall and proclaimed independence, though this was not formally recognized under international law.[12] In 1959, the 14th Dalai Lama revoked Tibet's Seventeen Point Agreement with China and initially supported the Tibetan independence movement, but since 2005 he has publicly agreed that Tibet is part of China and has not supported separatism.[13]

There is a concept in Tibetan history known as "mchod yon" (མཆོད་ཡོན), often translated as "priest and patron relationship". It describes the historical alliance between Tibetan Buddhist leaders and secular rulers, such as the Mongols, Manchus, and Chinese authorities. In this relationship, the secular patron (yon bdag) provides political protection and support to the religious figure, who in turn offers spiritual guidance and legitimacy. Proponents of this theory argue that it allowed Tibet to maintain a degree of autonomy in religious and cultural matters while ensuring political stability and protection.[14]

But critics, including Sam van Schaik, contend that the theory oversimplifies the situation and often obscures the political dominance more powerful states exert over Tibet. Historians such as Melvyn Goldstein have called Tibet a vassal state or tributary, subject to external control.[15] During the Yuan dynasty, Tibetan lamas held significant religious influence, but the Mongol Khans had ultimate political authority. Similarly, under the Qing Dynasty, which established control over Tibet in 1720, the region enjoyed a degree of autonomy, but all diplomatic agreements recognized Qing China's sovereign right to negotiate and conclude treaties and trade agreements involving Tibet. Since the 18th century, Chinese authorities have asserted the right to oversee the selection of Tibetan spiritual leaders, including the Dalai and Panchen Lamas.[16] This practice was formalized in 1793 through the "29-Article Ordinance for the More Effective Governing of Tibet".[17]

According to Tibetan Buddhist doctrine, the Dalai Lama chooses his reincarnation. In recent times, the 14th Dalai Lama has opposed Chinese government involvement, emphasizing that his reincarnation should not be subject to external political influence. He has also said that he could reincarnate as a woman or choose not to reincarnate at all.[18][19]

- ^ a b "Definition of Dalai Lama in English". Oxford Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 27 July 2013. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

The spiritual head of Tibetan Buddhism and, until the establishment of Chinese communist rule, the spiritual and temporal ruler of Tibet. Each Dalai Lama is believed to be the reincarnation of the bodhisattva Avalokitesvara, reappeared in a child when the incumbent Dalai Lama dies

- ^ a b "Dalai lama". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 26 February 2014. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

(formerly) the ruler and chief monk of Tibet, believed to be a reincarnation of Avalokitesvara and sought for among newborn children after the death of the preceding Dalai Lama

- ^ 陈庆英 (2003). 达赖喇嘛转世及历史定制. 五洲传播出版社. ISBN 978-7-5085-0272-4. 于是赠给尊号“圣识一切瓦齐尔达喇达赖喇嘛”的称号,“圣”,是超凡入圣,即超出尘世间之意;“识一切”,是藏传佛教对在显宗方面取得最高成就的僧人的尊称; “识一切”,是藏传佛教对在显宗方面取得最高成就的僧人的尊称;“瓦齐尔达喇“,是梵文Vajradhra的音译,译成藏语是 rdo- rje- vchange (多吉绛),译成汉语是执金刚,这是藏传佛教对于在密宗方面取得早高成就的僧人的尊称。 So he was given the title of "Holiness Knowing Everything Vazirdala Dalai Lama". "Holiness" means transcending the ordinary and entering the holy, that is, beyond the world; "Knowing Everything" is a Tibetan Buddhist title for monks who have achieved the highest achievements in the exoteric teachings; "Vazirdala" is the transliteration of the Sanskrit word Vajradhra, which is translated into Tibetan as rdo-rje-vchange (Dojijiang) and translated into Chinese as Vajra, which is a Tibetan Buddhist title for monks who have achieved high achievements in the esoteric teachings.

- ^ 陈庆英 (2003). 达赖喇嘛转世及历史定制. 五洲传播出版社. ISBN 978-7-5085-0272-4. 达赖喇嘛的名号产生于公元1578年。当时格鲁派大活佛索南嘉措应土默特蒙古首领顺义王俺达汗邀请到蒙古地方弘扬佛法。在青海仰华寺,索南嘉措对藏传佛教的理论进行了广泛的阐述,使这位蒙古首领对他产生了仰慕之心,于是赠给尊号“圣识一切瓦齐尔达喇达赖喇嘛”的称号. The name Dalai Lama was created in 1578 AD, in that year, Sonam Gyatso was invited by Anda (Altan Khan), the leader of the Tümed Mongols, to Mongol area (蒙古地方) to promote Buddhism. At Yanghua Monastery in [sic] Qinghai, Sonam Gyatso gave an extensive exposition of the theories of Tibetan Buddhism, which made the Mongol leader admire him and gave him the title "Holiness Knowing Everying Vajradhara Dalai Lama" title.

- ^ Peter Popham (29 January 2015). "Relentless: The Dalai Lama's Heart of Steel". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 29 April 2015. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

His mystical legitimacy – of huge importance to the faithful – stems from the belief that the Dalai Lamas are manifestations of Avalokiteshvara, the Bodhisattva of Compassion

- ^ Laird 2006, p. 12.

- ^ Woodhead, Linda (2016). Religions in the Modern World. Abingdon: Routledge. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-415-85881-6.

- ^ Religions in the Modern World: Traditions and Transformations. Taylor and Francis. Kindle locations 2519–2522.

- ^ Cantwell and Kawanami (2016). Religions in the Modern World. Routledge. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-415-85880-9.

- ^ Smith 1997, pp. 107–149.

- ^ Perkins, Dorothy (19 November 2013). Encyclopedia of China: History and Culture. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-93562-7.

- ^ Nomads of Western Tibet: The Survival of a Way of Life. University of California Press. 1 January 1990. ISBN 978-0-520-07211-4.

- ^ "Tibet part of China, Dalai Lama agrees". The Sydney Morning Herald. 15 March 2005. Retrieved 12 January 2025.

- ^ Chang, Simon T. (1 October 2011). "A 'realist' hypocrisy? Scripting sovereignty in Sino–Tibetan relations and the changing posture of Britain and the United States". Asian Ethnicity. 12 (3): 323–335. doi:10.1080/14631369.2011.605545. ISSN 1463-1369.

- ^ Goldstein, Melvyn C. (15 November 2023). A History of Modern Tibet, 1913-1951: The Demise of the Lamaist State. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-91176-5.

- ^ "Opinion | Tibet Couldn't Lose What It Never Had". The New York Times. 1 March 1994. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 12 January 2025.

- ^ Schwieger, Peter (31 March 2015). The Dalai Lama and the Emperor of China: A Political History of the Tibetan Institution of Reincarnation. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-53860-2.

- ^ "Dalai Lama likely to announce he will not reincarnate to save Tibetan Buddhism from China". The Tribune. Retrieved 12 January 2025.

- ^ "Dalai Lama sorry for saying female successor would have to be 'attractive'". NBC News. 2 July 2019. Retrieved 12 January 2025.

Previous Page Next Page