Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

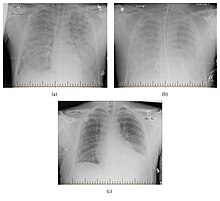

Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome

| Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

| Progression of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome | |

| Specialty | Pulmonology |

| Symptoms | Fever, cough, shortness of breath, headaches, muscle pains, lethargy, nausea, diarrhea |

| Complications | Respiratory failure, cardiac failure |

| Causes | Hantaviruses spread by rodents |

| Prevention | Rodent control |

| Treatment | Supportive, including mechanical ventilation |

| Medication | None |

| Prognosis | Poor, 30–60% case fatality rate |

Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS), also called hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome (HCPS), is a severe respiratory disease caused by hantaviruses. The main features of illness are microvascular leakage and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Symptoms occur anywhere from 1 to 8 weeks after exposure to the virus and come in three distinct phases. First, there is prodromal phase with flu-like symptoms such as fever, headache, muscle, shortness of breath, as well as low platelet count. Second, there is cardiopulmonary phase during which people experience elevated or irregular heart rate, cardiogenic shock, and pulmonary capillary leakage, which can lead to respiratory failure, low blood pressure, and buildup of fluid in the lungs and chest cavity. The final phase is recovery, which typically takes months, but difficulties with breathing can persist for up to two years. The disease has a case fatality rate of 30–60%.

HPS is caused mainly by infection with New World hantaviruses in the Americas. In North America, Sin Nombre virus is the most common cause of HPS and is transmitted by the Eastern deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus). In South America, Andes virus is the most common cause of HPS and is transmitted mainly by the long-tailed pygmy rice rat (Oligoryzomys longicaudatus). In their rodent hosts, these hantaviruses cause a persistent, asymptomatic infection. Transmission occurs mainly through inhalation of aerosols that contain rodent saliva, urine, or feces, but can also occur through contaminated food, bites, and scratches. Vascular endothelial cells and macrophages are the primary cells infected by hantaviruses, and infection causes abnormalities with blood clotting, all of which results in fluid leakage responsible for the more severe symptoms. Recovery from infection likely confers life-long protection.

The main way to prevent infection is to avoid or minimize contact with rodents that carry hantaviruses. Removing sources of food for rodents, safely cleaning up after them, and preventing them from entering one's house are all important means of protection. People who are at a risk of interacting with infected rodents can wear masks to protect themselves. No vaccines exist that protect against HPS. Initial diagnosis of infection can be made based on epidemiological information and symptoms. Confirmation of infection can be done by testing for hantavirus nucleic acid, proteins, or hantavirus-specific antibodies. Supportive treatment is always performed for HPS and entails continual cardiac monitoring and respiratory support, including mechanical ventilation, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), and hemofiltration. No specific antiviral drugs exist for hantavirus infection.

In North America, dozens of HPS cases occur each year, while in South America more than 100 cases occur every year. Isolated cases and small outbreaks have occurred in Europe and Turkey. The distribution of viruses that cause HPS is directly tied to the distribution of their natural reservoir. Transmission is also greatly influenced by environmental factors such as rainfall, temperature, and humidity, which affect the rodent population and virus transmissibility. The discovery of HPS came in 1993 during an outbreak in the Four Corners region of the US, which was indirectly caused by the El Niño climate pattern. Sin Nombre virus was found to be responsible for the outbreak, and since then numerous other hantaviruses that cause HPS have been identified throughout the Americas.

Previous Page Next Page

متلازمة فيروس هانتا الرئوية Arabic متلازمة فيروس هانتا الرئويه ARZ Síndrome pulmonar por hantavirus Spanish Syndrome pulmonaire à hantavirus French Հանտավիրուսային կարդիոպուլմոնալ համախտանիշ HY ハンタウイルス肺症候群 Japanese ହାଣ୍ଟାଭୂତାଣୁ ପଲମୋନାରୀ ସିଣ୍ଡ୍ରୋମ OR Hantawirusowy zespół płucny Polish Síndrome pulmonar por hantavírus Portuguese Хантавирусный кардиопульмональный синдром Russian