Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

Leon Trotsky

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. When this tag was added, its readable prose size was 18,400 words. (December 2024) |

Leon Trotsky | |

|---|---|

| Лев Троцкий | |

Trotsky c. 1920 | |

| People's Commissar for Military and Naval Affairs of the Soviet Union[a] | |

| In office 14 March 1918 – 12 January 1925 | |

| Premier | |

| Preceded by | Nikolai Podvoisky |

| Succeeded by | Mikhail Frunze |

| People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs of the Russian SFSR | |

| In office 8 November 1917 – 13 March 1918 | |

| Premier | Vladimir Lenin |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Georgy Chicherin |

| Chairman of the Petrograd Soviet | |

| In office 20 September 1917 – 26 December 1917 | |

| Preceded by | Nikolay Chkheidze |

| Succeeded by | Grigory Zinoviev |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Lev Davidovich Bronstein 7 November 1879 (N.S.) Yanovka, Russian Empire |

| Died | 21 August 1940 (aged 60) Mexico City, Mexico |

| Manner of death | Assassination |

| Resting place | Leon Trotsky House Museum, Mexico City, Mexico |

| Citizenship |

|

| Political party |

|

| Spouses | |

| Children | |

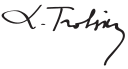

| Signature |  |

Central institution membership Other offices held

| |

Lev Davidovich Bronstein[b] (7 November [O.S. 26 October] 1879 – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky,[c] was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and political theorist. He was a central figure in the 1905 Revolution, October Revolution of 1917, Russian Civil War, and establishment of the Soviet Union, from which he was exiled in 1929 before his assassination in 1940. Trotsky and Vladimir Lenin were widely considered the two most prominent Soviet figures from 1917 until Lenin's death in 1924. Ideologically a Marxist and a Leninist, Trotsky's ideas inspired a school of Marxism known as Trotskyism.

Born into a wealthy Jewish family in Ukraine, then part of the Russian Empire, Trotsky joined the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party in 1898. He was arrested for revolutionary activities and exiled to Siberia, but in 1902 escaped to London, where he met Lenin and wrote for the party paper Iskra. Trotsky initially sided with the Mensheviks against Lenin's Bolsheviks in the party's 1903 schism, but declared himself non-factional in 1904. During the 1905 Revolution, Trotsky returned to Russia and was elected chairman of the Saint Petersburg Soviet. He was again exiled to Siberia, but escaped in 1907 and lived in Europe and the U.S. After the February Revolution of 1917, Trotsky returned to Russia and joined the Bolsheviks. As the chairman of the Petrograd Soviet, he helped lead the October Revolution, and in Lenin's first government he was appointed the People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs and led negotiations for the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, by which Russia withdrew from World War I. He served as the People's Commissar for Military and Naval Affairs from 1918 to 1925, during which he built the Red Army and led it to victory in the civil war. In 1922, Lenin formed a bloc with Trotsky against the Soviet bureaucracy[3] and several times proposed that he become one of his deputy premiers,[4] but Trotsky declined the post.[5] Beginning in 1923, Trotsky led the party's Left Opposition faction, which opposed the market concessions of the New Economic Policy.

After Lenin's death in 1924, Trotsky emerged as the most prominent critic of Joseph Stalin, but was quickly outmaneuvered by him politically. Trotsky was expelled from the Politburo in 1926 and from the party in 1927, internally exiled to Alma Ata in 1928, and deported in 1929. He lived in Turkey, France, and Norway before settling in Mexico in 1937. In exile, Trotsky wrote polemics against Stalinism, supporting proletarian internationalism against Stalin's theory of socialism in one country. Trotsky's theory of permanent revolution posited that the socialist revolution could only survive if spread to the advanced capitalist countries. In The Revolution Betrayed (1936), Trotsky argued that the Soviet Union had become a "degenerated workers' state" and dictatorship due to its isolation, and in 1938, founded the Fourth International as an alternative to the Soviet-led Comintern. After being sentenced to death in absentia at the first Moscow show trial in 1936, Trotsky was assassinated in 1940 at his house in Mexico City by Stalinist agent Ramón Mercader.

Written out of official Soviet history under Stalin, Trotsky was one of the few of his rivals who was never politically rehabilitated by later leaders. In the West, Trotsky emerged as a hero of the anti-Stalinist left for his defense of a more democratic, internationalist form of socialism[6][7] against Stalinist totalitarianism, and for his intellectual contributions to Marxism. While some of his wartime actions are controversial, such as his ideological defence of the Red Terror[8] and suppression of the Kronstadt rebellion, scholarship ranks Trotsky's leadership of the Red Army highly among historical figures, and he is credited for his major involvement with the military, economic, cultural[9] and political development of the Soviet Union.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

- ^ Cliff, Tony (2004) [1976]. "Lenin Rearms the Party". All Power to the Soviets: Lenin 1914–1917. Vol. 2. Chicago: Haymarket Books. p. 139. ISBN 9781931859103. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

Trotsky was a leader of a small group, the Mezhraionts, consisting of almost four thousand members.

- ^ "Trotsky". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ Mccauley 2014, p. 59; Deutscher 2003b, p. 63; Kort 2015, p. 166; Service 2010, p. 301–20; Pipes 1993, p. 469; Volkogonov 1996, p. 242; Lewin 2005, p. 67; Tucker 1973, p. 336; Figes 2017, pp. 796, 797; D'Agostino 2011, p. 67.

- ^ Getty 2013b, p. 53; Douds 2019b, p. 165.

- ^ Bullock 1991b, p. 163; Rees & Rosa 1992b, p. 129; Kosheleva 1995b, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Barnett, Vincent (7 March 2013). A History of Russian Economic Thought. Routledge. p. 101. ISBN 978-1-134-26191-8.

- ^ Deutscher 2015a, pp. 1053.

- ^ "Leon Trotsky: Terrorism and Communism (Chapter 4)". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- ^ Knei-Paz 1979, p. 296; Kivelson & Neuberger 2008, p. 149.

Previous Page Next Page