Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

Natural law

Natural law[1] (Latin: ius naturale, lex naturalis) is a philosophical and legal theory that posits the existence of a set of inherent laws derived from nature and universal moral principles, which are discoverable through reason. In ethics, natural law theory[2] asserts that certain rights and moral values are inherent in human nature and can be understood universally, independent of enacted laws or societal norms. In jurisprudence, natural law—sometimes referred to as iusnaturalism[3] or jusnaturalism,[4] but not to be confused with what is called simply naturalism in legal philosophy[5][6]—holds that there are objective legal standards based on morality that underlie and inform the creation, interpretation, and application of human-made laws. This contrasts with positive law (as in legal positivism),[7] which emphasizes that laws are rules created by human authorities and are not necessarily connected to moral principles. Natural law can refer to "theories of ethics, theories of politics, theories of civil law, and theories of religious morality",[8] depending on the context in which naturally-grounded practical principles are claimed to exist.

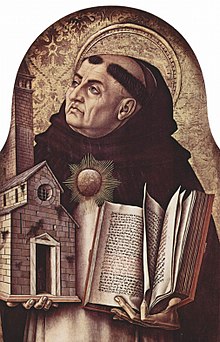

In Western tradition, natural law was anticipated by the pre-Socratics, for example, in their search for principles that governed the cosmos and human beings. The concept of natural law was documented in ancient Greek philosophy, including Aristotle,[9] and was mentioned in ancient Roman philosophy by Cicero. References to it are also found in the Old and New Testaments of the Bible, and were later expounded upon in the Middle Ages by Christian philosophers such as Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas. The School of Salamanca made notable contributions during the Renaissance.

Although the central ideas of natural law had been part of Christian thought since the Roman Empire, its foundation as a consistent system was laid by Aquinas, who synthesized and condensed his predecessors' ideas into his Lex Naturalis (lit. 'natural law').[10] Aquinas argues that because human beings have reason, and because reason is a spark of the divine, all human lives are sacred and of infinite value compared to any other created object, meaning everyone is fundamentally equal and bestowed with an intrinsic basic set of rights that no one can remove.

Modern natural law theory took shape in the Age of Enlightenment, combining inspiration from Roman law, Christian scholastic philosophy, and contemporary concepts such as social contract theory. It was used in challenging the theory of the divine right of kings, and became an alternative justification for the establishment of a social contract, positive law, and government—and thus legal rights—in the form of classical republicanism. John Locke was a key Enlightenment-era proponent of natural law, stressing its role in the justification of property rights and the right to revolution.[11] In the early decades of the 21st century, the concept of natural law is closely related to the concept of natural rights and has libertarian and conservative proponents.[12] Indeed, many philosophers, jurists and scholars use natural law synonymously with natural rights (Latin: ius naturale) or natural justice;[13] others distinguish between natural law and natural right.[14]

Some scholars point out that the concept of natural law has been used by philosophers throughout history also in a different sense from those mentioned above, e.g. for the law of the strongest, which can be observed to hold among all members of the animal kingdom, or as the principle of self-preservation, inherent as an instinct in all living beings.[15]

- ^ "Natural Law". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 2022-02-23. Retrieved 2020-10-19.

- ^ Murphy, Mark (2019). "The Natural Law Tradition in Ethics". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2019 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 2025-01-30.

- ^ Vallejo, Catalina (2012). Plurality of Peaces in Legal Action: Analyzing Constitutional Objections to Military Services in Colombia. Münster: LIT. p. 62. ISBN 978-3-643-90282-5.

- ^ Wintgens, Luc J. (2013-04-17). The Law in Philosophical Perspectives: My Philosophy of Law. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 264. ISBN 978-94-015-9317-5.

- ^ Leiter, Brian; Etchemendy, Matthew X. (2021). "Naturalism in Legal Philosophy". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2021 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 2025-01-30.

- ^ Bix, Brian (2020-09-22). "Dan Priel's Naturalism". Jurisprudence. Retrieved 2025-01-30.

- ^ Finnis, John (2020). "Natural Law Theories". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2020 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on 2021-09-10. Retrieved 2020-10-19.

- ^ Murphy, Mark (2019). "The Natural Law Tradition in Ethics". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2019 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on 2021-11-13. Retrieved 2020-10-19.

- ^ Rommen, Heinrich A. (1959) [1947]. The Natural Law: A Study in Legal and Social Philosophy. Translated by Hanley, Thomas R. B. Herder Book Co. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-86597-161-5.

- ^ Maritain, Jacques (9 October 2018). "Human Rights and Natural Law". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 13 November 2021. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ^ Locke, John (April 22, 2003) [1690]. Second Treatise of Government. Archived from the original on May 30, 2024. Retrieved 2024-06-11 – via Project Gutenberg.

- ^ van Duffel, Siegfried (2004). "Libertarian Natural Rights" (PDF). Critical Review. 16 (4). ISSN 0891-3811.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Shellenswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Strauss, Leo (1968). "Natural Law". International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences. London: Macmillan Publishers.

- ^ Vacura, Miroslav (2022). "Three concepts of natural law". Philosophy and Society. 33 (3): 601–620. doi:10.2298/FID2203601V. ISSN 2683-3867.

Previous Page Next Page