Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

Status epilepticus

| Status epilepticus | |

|---|---|

| |

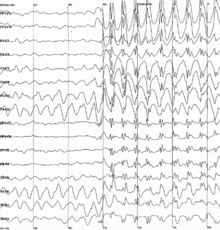

| Generalized 3 Hz spike-and-wave discharges on an electroencephalogram | |

| Specialty | Emergency medicine, neurology |

| Symptoms | Regular pattern of contraction and extension of the arms and legs, movement of one part of the body, unresponsive[1] |

| Duration | >5 minutes[1] |

| Risk factors | Epilepsy, underlying problem with the brain[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Blood sugar, imaging of the head, blood tests, electroencephalogram[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Psychogenic nonepileptic seizures, movement disorders, meningitis, delirium[1] |

| Treatment | Benzodiazepines, fosphenytoin, phenytoin,[1] paraldehyde (rarely used) |

| Prognosis | ~20% thirty-day risk of death[1] |

| Frequency | 40 per 100,000 people per year[2] |

Status epilepticus (SE), or status seizure, is a medical condition with abnormally prolonged seizures, and which can have long-term consequences [3], manifesting as a single seizure lasting more than a defined time (time point 1), or 2 or more seizures over the same period without the person returning to normal between them. The seizures can be of the tonic–clonic type, with a regular pattern of contraction and extension of the arms and legs, also known as Convlusive Status Epilepticus or of types that do not involve contractions, such as absence seizures or complex partial seizures.[1] Convlusive Status epilepticus is a life-threatening medical emergency, particularly if treatment is delayed.[1]For convulsive status epilepticus, the most dangerous type, 5 minutes is the time point at which the seizure or seizures would be considered status epilepticus, so this is defined as a convulsion lasting more than 5 minutes, or two convulsions within 5 minutes without complete recovery. The risk of damage starts to accrue after 30 minutes (time point 2) for convulsive status epilepticus.[4][1] . For other seizure types, the time points may vary. Previous definitions used a 30-minute time limit irrespective of type of seizure.[2]

Status epilepticus may occur in those with a history of epilepsy as well as those with an underlying problem of the brain.[2] These underlying brain problems may include trauma, infections, or strokes, among others.[2][5] Diagnosis often involves checking the blood sugar, imaging of the head, a number of blood tests, and an electroencephalogram.[1] Psychogenic nonepileptic seizures may present similarly to status epilepticus.[1] Other conditions that may also appear to be status epilepticus include low blood sugar, movement disorders, meningitis, and delirium, among others.[1] Status epilepticus can also appear when tuberculous meningitis becomes very severe.

Benzodiazepines are the preferred initial treatment, after which typically phenytoin is given.[1] Possible benzodiazepines include intravenous lorazepam as well as intramuscular injections of midazolam.[6] A number of other medications may be used if these are not effective, such as phenobarbital, propofol, or ketamine.[1] After initial treatment with benzodiazepines, typical antiseizure drugs should be given, including valproic acid (valproate), fosphenytoin, levetiracetam, or a similar substance(s).[7] While empirically based treatments exist, few head-to-head clinical trials exist, so the best approach remains undetermined.[7] This said, "consensus-based" best practices are offered by the Neurocritical Care Society.[7] Intubation may be required to help maintain the person's airway.[1] Between 10% and 30% of people who have status epilepticus die within 30 days.[1] The underlying cause, the person's age, and the length of the seizure are important factors in the outcome.[2] Status epilepticus occurs in up to 40 per 100,000 people per year.[2] Those with status epilepticus make up about 1% of people who visit the emergency department.[1]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Al-Mufti, F; Claassen, J (Oct 2014). "Neurocritical Care: Status Epilepticus Review". Critical Care Clinics. 30 (4): 751–764. doi:10.1016/j.ccc.2014.06.006. PMID 25257739.

- ^ a b c d e f g Trinka, E; Höfler, J; Zerbs, A (September 2012). "Causes of status epilepticus". Epilepsia. 53 (Suppl 4): 127–38. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03622.x. PMID 22946730. S2CID 5294771.

- ^ Trinka, E., Cock, H., Hesdorffer, D., Rossetti, A. O., Scheffer, I. E., Shinnar, S., Shorvon, S., & Lowenstein, D. H. (2015). A definition and classification of status epilepticus--Report of the ILAE Task Force on Classification of Status Epilepticus. Epilepsia, 56(10), 1515–1523. doi:10.1111/epi.13121

- ^ Drislane, Frank (19 March 2020). Garcia, Paul; Edlow, Jonathan (eds.). "Convulsive status epilepticus in adults: Classification, clinical features, and diagnosis". UpToDate. 34.2217. Wolters Kluwer.

- ^ Trinka, E., Cock, H., Hesdorffer, D., Rossetti, A. O., Scheffer, I. E., Shinnar, S., Shorvon, S., & Lowenstein, D. H. (2015). A definition and classification of status epilepticus--Report of the ILAE Task Force on Classification of Status Epilepticus. Epilepsia, 56(10), 1515–1523. doi:10.1111/epi.13121

- ^ Prasad, M; Krishnan, PR; Sequeira, R; Al-Roomi, K (Sep 10, 2014). "Anticonvulsant therapy for status epilepticus". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (9): CD003723. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003723.pub3. PMC 7154380. PMID 25207925.

- ^ a b c Drislane, Frank (15 June 2021). Garcia, Paul; Edlow, Jonathan (eds.). "Convulsive status epilepticus in adults: Treatment and prognosis: Initial Treatment". UpToDate. 52.96933. Wolters Kluwer.

Previous Page Next Page