Back متلازمة انسحاب كحولي Arabic Syndrom gostwng lefelau alcohol CY Síndrome de abstinencia del alcohol Spanish سندرم ترک الکل FA Alkoholivieroitusoireyhtymä Finnish Syndrome de sevrage alcoolique French תסמונת גמילה מאלכוהול HE शराब प्रत्याहार सिंड्रोम HI Ալկոհոլային զրկանքի համախտանիշ HY Sindrome da astinenza da alcol Italian

| Alcohol withdrawal syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ethanol | |

| Specialty | Toxicology, addiction medicine, intensive care medicine, psychiatry |

| Symptoms | Anxiety, shakiness, sweating, vomiting, fast heart rate, mild fever[1] |

| Complications | Seizures, delirium tremens, death |

| Usual onset | Six hours following the last drink[2] |

| Duration | Up to a week[2] |

| Causes | Reduction or cessation of alcohol intake after a period of excessive use[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol (CIWA-Ar)[3] |

| Treatment | Benzodiazepines, thiamine[2] |

| Frequency | ~50% of people with alcoholism upon reducing use[3] |

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome (AWS) is a set of symptoms that can occur following a reduction in alcohol use after a period of excessive use.[1] Symptoms typically include anxiety, shakiness, sweating, vomiting, fast heart rate, and a mild fever.[1] More severe symptoms may include seizures, and delirium tremens (DTs); which can be fatal in untreated patients.[1] Symptoms start at around 6 hours after the last drink.[2] Peak incidence of seizures occurs at 24 to 36 hours[5] and peak incidence of delirium tremens is at 48 to 72 hours.[6]

Alcohol withdrawal may occur in those who are alcohol dependent.[1] This may occur following a planned or unplanned decrease in alcohol intake.[1] The underlying mechanism involves a decreased responsiveness of GABA receptors in the brain.[3] The withdrawal process is typically followed using the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol scale (CIWA-Ar).[3]

The typical treatment of alcohol withdrawal is with benzodiazepines such as chlordiazepoxide or diazepam.[2] Often the amounts given are based on a person's symptoms.[2] Thiamine is recommended routinely.[2] Electrolyte problems and low blood sugar should also be treated.[2] Early treatment improves outcomes.[2]

In the Western world about 15% of people have problems with alcoholism at some point in time.[3] Alcohol depresses the central nervous system, slowing cerebral messaging and altering the way signals are sent and received. Progressively larger amounts of alcohol are needed to achieve the same physical and emotional results. The drinker eventually must consume alcohol just to avoid the physical cravings and withdrawal symptoms. About half of people with alcoholism will develop withdrawal symptoms upon reducing their use, with four percent developing severe symptoms.[3] Among those with severe symptoms up to 15% die.[2] Symptoms of alcohol withdrawal have been described at least as early as 400 BC by Hippocrates.[7][8] It is not believed to have become a widespread problem until the 1700s.[8]

- ^ a b c d e f g National Clinical Guideline Centre (2010). "2 Acute Alcohol Withdrawal". Alcohol Use Disorders: Diagnosis and Clinical Management of Alcohol-Related Physical Complications (No. 100 ed.). London: Royal College of Physicians (UK). Archived from the original on 31 January 2014. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Simpson SA, Wilson MP, Nordstrom K (September 2016). "Psychiatric Emergencies for Clinicians: Emergency Department Management of Alcohol Withdrawal". The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 51 (3): 269–73. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.03.027. PMID 27319379.

- ^ a b c d e f Schuckit MA (November 2014). "Recognition and management of withdrawal delirium (delirium tremens)". The New England Journal of Medicine. 371 (22): 2109–13. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1407298. PMID 25427113. S2CID 205116954.

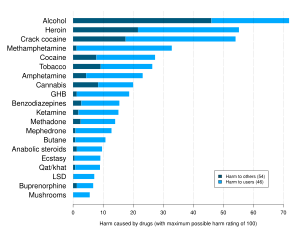

- ^ Nutt DJ, King LA, Phillips LD (November 2010). "Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis". Lancet. 376 (9752): 1558–1565. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.690.1283. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61462-6. PMID 21036393. S2CID 5667719.

- ^ Liu, Grant T.; Volpe, Nicholas J.; Galetta, Steven L. (1 January 2019), Liu, Grant T.; Volpe, Nicholas J.; Galetta, Steven L. (eds.), "12 - Visual Hallucinations and Illusions", Liu, Volpe, and Galetta's Neuro-Ophthalmology (Third Edition), Elsevier, pp. 395–413, ISBN 978-0-323-34044-1, retrieved 12 June 2023

- ^ Helmus, Christian; Spahn, James G. (September 1974). "Delirium Tremens in Head and Neck Surgery". The Laryngoscope. 84 (9): 1479–1488. doi:10.1288/00005537-197409000-00004. ISSN 0023-852X. PMID 4412722. S2CID 28374619.

- ^ Martin SC (2014). The SAGE Encyclopedia of Alcohol: Social, Cultural, and Historical Perspectives. SAGE Publications. p. Alcohol Withdrawal Scale. ISBN 9781483374383. Archived from the original on 22 October 2016.

- ^ a b Kissin B, Begleiter H (2013). The Biology of Alcoholism: Volume 3: Clinical Pathology. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 192. ISBN 9781468429374. Archived from the original on 22 October 2016.