Back Hipnose AF Oferswefn ANG تنويم مغناطيسي Arabic ايحاء ARZ Hipnosis AST Hipnoz AZ هیپنوتیسم AZB Гіпноз BE Гіпноз BE-X-OLD Хипноза Bulgarian

| Hypnosis | |

|---|---|

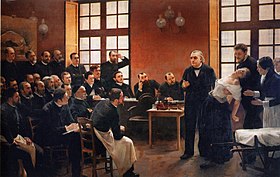

Jean-Martin Charcot demonstrating hypnosis on a "hysterical" Salpêtrière patient, "Blanche" (Marie Wittman), who is supported by Joseph Babiński[1] | |

| MeSH | D006990 |

| Hypnosis |

|---|

Hypnosis is a human condition involving focused attention (the selective attention/selective inattention hypothesis, SASI),[2] reduced peripheral awareness, and an enhanced capacity to respond to suggestion.[3]

There are competing theories explaining hypnosis and related phenomena. Altered state theories see hypnosis as an altered state of mind or trance, marked by a level of awareness different from the ordinary state of consciousness.[4][5] In contrast, non-state theories see hypnosis as, variously, a type of placebo effect,[6][7] a redefinition of an interaction with a therapist[8] or a form of imaginative role enactment.[9][10][11]

During hypnosis, a person is said to have heightened focus and concentration[12][13] and an increased response to suggestions.[14] Hypnosis usually begins with a hypnotic induction involving a series of preliminary instructions and suggestions. The use of hypnosis for therapeutic purposes is referred to as "hypnotherapy",[15] while its use as a form of entertainment for an audience is known as "stage hypnosis", a form of mentalism.

Hypnosis-based therapies for the management of irritable bowel syndrome and menopause are supported by evidence.[16][17] The use of hypnosis as a form of therapy to retrieve and integrate early trauma is controversial within the scientific mainstream. Research indicates that hypnotising an individual may aid the formation of false memories,[18][19] and that hypnosis "does not help people recall events more accurately".[20] Medical hypnosis is often considered pseudoscience or quackery.[21]

- ^ See: A Clinical Lesson at the Salpêtrière.

- ^ Hall, Harriet (2021). "Hypnosis revisited". Skeptical Inquirer. 45 (2): 17–19.

- ^ In 2015, the American Psychological Association Division 30 defined hypnosis as a "state of consciousness involving focused attention and reduced peripheral awareness characterized by an enhanced capacity for response to suggestion". For critical commentary on this definition, see: Lynn SJ, Green JP, Kirsch I, Capafons A, Lilienfeld SO, Laurence JR, Montgomery GH (April 2015). "Grounding Hypnosis in Science: The "New" APA Division 30 Definition of Hypnosis as a Step Backward". The American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis. 57 (4): 390–401. doi:10.1080/00029157.2015.1011472. PMID 25928778. S2CID 10797114.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, 2004: "a special psychological state with certain physiological attributes, resembling sleep only superficially and marked by a functioning of the individual at a level of awareness other than the ordinary conscious state".

- ^ Erika Fromm; Ronald E. Shor (2009). Hypnosis: Developments in Research and New Perspectives. Rutgers. ISBN 978-0-202-36262-5. Archived from the original on 2 July 2023. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ Kirsch I (October 1994). "Clinical hypnosis as a nondeceptive placebo: empirically derived techniques". The American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis. 37 (2): 95–106. doi:10.1080/00029157.1994.10403122. PMID 7992808.

- ^ Kirsch, I., "Clinical Hypnosis as a Nondeceptive Placebo", pp. 211–25 in Kirsch, I., Capafons, A., Cardeña-Buelna, E., Amigó, S. (eds.), Clinical Hypnosis and Self-Regulation: Cognitive-Behavioral Perspectives, American Psychological Association, (Washington), 1999 ISBN 1-55798-535-9

- ^ Theodore X. Barber (1969). Hypnosis: A Scientific Approach. J. Aronson, 1995. ISBN 978-1-56821-740-6.

- ^ Lynn S, Fassler O, Knox J (2005). "Hypnosis and the altered state debate: something more or nothing more?". Contemporary Hypnosis. 22: 39–45. doi:10.1002/ch.21.

- ^ Coe WC, Buckner LG, Howard ML, Kobayashi K (July 1972). "Hypnosis as role enactment: focus on a role specific skill". The American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis. 15 (1): 41–45. doi:10.1080/00029157.1972.10402209. PMID 4679790.

- ^ Steven J. Lynn; Judith W. Rhue (1991). Theories of hypnosis: current models and perspectives. Guilford Press. ISBN 978-0-89862-343-7. Archived from the original on 2 July 2023. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ^ Orne, M. T. (1962). On the social psychology of the psychological experiment: With particular reference to demand characteristics and their implications. American Psychologist, 17, 776-783

- ^ Segi, Sherril (2012). "Hypnosis for pain management, anxiety and behavioral disorders". The Clinical Advisor: For Nurse Practitioners. 15 (3): 80. ISSN 1524-7317.

- ^ Lyda, Alex. "Hypnosis Gaining Ground in Medicine." Columbia News Archived 7 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Columbia.edu. Retrieved on 1 October 2011.

- ^ Spanos, N. P., Spillane, J., & McPeake, J. D. (1976). Cognitive strategies and response to suggestion in hypnotic and task-motivated subjects. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 18, 252-262.

- ^ Lacy, Brian E.; Pimentel, Mark; Brenner, Darren M.; Chey, William D.; Keefer, Laurie A.; Long, Millie D.; Moshiree, Baha (January 2021). "ACG Clinical Guideline: Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome". American Journal of Gastroenterology. 116 (1): 17–44. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000001036. ISSN 0002-9270. PMID 33315591.

- ^ "Nonhormonal management of menopause-associated vasomotor symptoms: 2015 position statement of The North American Menopause Society". Menopause. 22 (11): 1155–1172, quiz 1173–1174. November 2015. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000546. ISSN 1530-0374. PMID 26382310. S2CID 14841660. Archived from the original on 22 March 2021. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ Lynn, Steven Jay; Krackow, Elisa; Loftus, Elizabeth F.; Locke, Timothy G.; Lilienfeld, Scott O. (2014). "Constructing the past: problematic memory recovery techniques in psychotherapy". In Lilienfeld, Scott O.; Lynn, Steven Jay; Lohr, Jeffrey M. (eds.). Science and pseudoscience in clinical psychology (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press. pp. 245–275. ISBN 9781462517510. OCLC 890851087.

- ^ French, Christopher C. (2023). "Hypnotic Regression and False Memories". In Ballester-Olmos, V.J.; Heiden, Richard W. (eds.). The Reliability of UFO Witness Testimony. Turin, Italy: UPIAR. pp. 283–294. ISBN 9791281441002.

- ^ Hall, Celia (26 August 2001). "Hypnosis does not help accurate memory recall, says study". Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ Naudet, Florian; Falissard, Bruno; Boussageon, Rémy; Healy, David (2015). "Has evidence-based medicine left quackery behind?" (PDF). Internal and Emergency Medicine. 10 (5): 631–634. doi:10.1007/s11739-015-1227-3. ISSN 1970-9366. PMID 25828467. S2CID 20697592.

Treatments such as relaxation techniques, chiropractic, therapeutic massage, special diets, megavitamins, acupuncture, naturopathy, homeopathy, hypnosis and psychoanalysis are often considered as pseudoscience or quackery with no credible or respectable place in medicine, because in evaluation they have not been shown to work