Back بريغابالين Arabic پریگابالین AZB Прегабалин Bulgarian প্রিগাবালিন Bengali/Bangla Pregabalina Catalan Pregabalin Czech Pregabalin German Πρεγκαμπαλίνη Greek Pregabalina Spanish پرگابالین FA

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /priˈɡæbəlɪn/ |

| Trade names | Lyrica, others[1] |

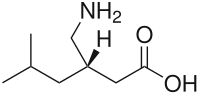

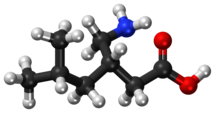

| Other names | 3-Isobutyl-GABA; (S)-3-Isobutyl-γ-aminobutyric acid; Isobutylgaba; CI-1008; PD-144723 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a605045 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category | |

| Dependence liability | Physical: High[4] Psychological: Moderate[4] |

| Addiction liability | Low[4] (but varying with dosage and route of administration) |

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Oral: ≥90%[11] |

| Protein binding | <1%[12] |

| Metabolites | N-methylpregabalin[11] |

| Onset of action | May occur within a week (pain)[13] |

| Elimination half-life | 4.5–7 hours[14] (mean 6.3 hours)[14][15] |

| Duration of action | 8–12 hours [16] |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.119.513 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C8H17NO2 |

| Molar mass | 159.229 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Pregabalin, sold under the brand name Lyrica among others, is an anticonvulsant, analgesic, and anxiolytic amino acid medication used to treat epilepsy, neuropathic pain, fibromyalgia, restless legs syndrome, opioid withdrawal, and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD).[13][17][18] Pregabalin also has antiallodynic properties.[19][20][21] Its use in epilepsy is as an add-on therapy for partial seizures.[13] When used before surgery, it reduces pain but results in greater sedation and visual disturbances.[22] It is taken by mouth.[13]

Common side effects can include headache, dizziness, sleepiness, confusion, trouble with memory, poor coordination, dry mouth, problems with vision, and weight gain.[13][23] Serious side effects may include angioedema, and drug misuse.[13] As with all other drugs approved by the FDA for treating epilepsy, the pregabalin labeling warns of an increased suicide risk when combined with other drugs.[24][13] When pregabalin is taken at high doses over a long period of time, addiction may occur, but if taken at usual doses the risk is low.[4] Use during pregnancy or breastfeeding is of unclear safety.[25]

It is a gabapentinoid medication (GABA analogue) which are drugs that are derivatives of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), an inhibitory neurotransmitter.[26][27][28][29] Although pregabalin is inactive at GABA receptors and GABA synapses, it acts by binding specifically to the α2δ-1 protein that was first described as an auxiliary subunit of voltage-gated calcium channels (See Pharmcodynamics).[13][30][31]

Pregabalin was approved for medical use in the United States in 2004.[13] It was developed as a successor to the related gabapentin.[32] It is available as a generic medication.[23][33][34][35][36] In 2022, it was the 91st most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 7 million prescriptions.[37][38] In the US, pregabalin is a Schedule V controlled substance under the Controlled Substances Act of 1970,[13] which means that the drug has low abuse potential compared to substances in Schedules I-IV, however, there is still a potential for misuse.[39] Despite the low abuse potential, there have been reports of euphoria, improved happiness, excitement, calmness, and a "high" similar to marijuana with the use of pregabalin; there is a potential for developing dependence on these substances, and withdrawal symptoms may occur if the medication is abruptly discontinued.[40][41] It is a Class C controlled substance in the UK.[42] Therefore, pregabalin requires a prescription.[43][44] Furthermore, the prescription must clearly set forth the dose.[45] Pregabalin has potential for misuse. It can bring about an elevated mood in users. It can also have serious side effects, particularly when used in combination with other drugs.[45][46]

- ^ "Pregabalin". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on August 28, 2019. Retrieved November 7, 2016.

- ^ "Avoid prescribing pregabalin in pregnancy if possible". Australian Department of Health and Aged Care. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ "Product Information safety updates - January 2023". Australian Department of Health and Aged Care. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Schifano F (June 2014). "Misuse and abuse of pregabalin and gabapentin: cause for concern?". CNS Drugs. 28 (6): 491–496. doi:10.1007/s40263-014-0164-4. PMID 24760436.

- ^ "Prescription medicines: registration of new generic medicines and biosimilar medicines, 2017". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). June 21, 2022. Archived from the original on July 6, 2023. Retrieved March 30, 2024.

- ^ Anvisa (March 31, 2023). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published April 4, 2023). Archived from the original on August 3, 2023. Retrieved August 16, 2023.

- ^ "Lyrica Consumer Medicine Information" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on December 4, 2023. Retrieved December 4, 2023.

- ^ "Lyrica Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). February 27, 2023. Archived from the original on December 21, 2023. Retrieved December 21, 2023.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

DailyMed-2020was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Lyrica EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). July 6, 2004. Archived from the original on December 21, 2023. Retrieved December 21, 2023.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

EMA2013was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Bock2010was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Pregabalin". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on December 2, 2019. Retrieved February 3, 2019.

- ^ a b Expert Committee on Drug Dependence Forty-first Meeting (November 2018). Critical Review Report: Pregabalin (PDF) (Report). Geneva: World Health Organization. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 26, 2020.

- ^ Cross AL, Viswanath O, Sherman AI (July 19, 2022). "Pregabalin". StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29261857. Archived from the original on August 3, 2022. Retrieved August 27, 2022 – via NCBI Bookshelf.

- ^ "BNF Pregabalin". NICE. November 16, 2018. Retrieved June 19, 2024.

- ^ Frampton JE (September 2014). "Pregabalin: a review of its use in adults with generalized anxiety disorder". CNS Drugs. 28 (9): 835–854. doi:10.1007/s40263-014-0192-0. PMID 25149863. S2CID 5349255.

- ^ Iftikhar IH, Alghothani L, Trotti LM (December 2017). "Gabapentin enacarbil, pregabalin and rotigotine are equally effective in restless legs syndrome: a comparative meta-analysis". European Journal of Neurology. 24 (12): 1446–1456. doi:10.1111/ene.13449. PMID 28888061. S2CID 22262972.

- ^ Wyllie E, Cascino GD, Gidal BE, Goodkin HP (February 17, 2012). Wyllie's Treatment of Epilepsy: Principles and Practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 423. ISBN 978-1-4511-5348-4.

- ^ Kirsch D (October 10, 2013). Sleep Medicine in Neurology. John Wiley & Sons. p. 241. ISBN 978-1-118-76417-6.

- ^ Frye M, Moore K (2009). "Gabapentin and Pregabalin". In Schatzberg AF, Nemeroff CB (eds.). The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychopharmacology. pp. 767–77. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9781585623860.as38. ISBN 978-1-58562-309-9. Archived from the original on February 27, 2024. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- ^ Mishriky BM, Waldron NH, Habib AS (January 2015). "Impact of pregabalin on acute and persistent postoperative pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 114 (1): 10–31. doi:10.1093/bja/aeu293. PMID 25209095.

- ^ a b British National Formulary: BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. p. 323. ISBN 9780857113382.

- ^ Britton JW, Shih JJ (2010). "Antiepileptic drugs and suicidality". Drug, Healthcare and Patient Safety. 2: 181–189. doi:10.2147/DHPS.S13225. PMC 3108698. PMID 21701630.

- ^ "Pregabalin Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on March 21, 2019. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ Calandre EP, Rico-Villademoros F, Slim M (2016). "Alpha2delta ligands, gabapentin, pregabalin and mirogabalin: a review of their clinical pharmacology and therapeutic use". Expert Rev Neurother. 16 (11): 1263–1277. doi:10.1080/14737175.2016.1202764. PMID 27345098. S2CID 33200190.

- ^ Dooley DJ, Taylor CP, Donevan S, Feltner D (2007). "Ca2+ channel alpha2delta ligands: novel modulators of neurotransmission". Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 28 (2): 75–82. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2006.12.006. PMID 17222465.

- ^ Elaine Wyllie, Gregory D. Cascino, Barry E. Gidal, Howard P. Goodkin (February 17, 2012). Wyllie's Treatment of Epilepsy: Principles and Practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 423. ISBN 978-1-4511-5348-4.

- ^ Honorio Benzon, James P. Rathmell, Christopher L. Wu, Dennis C. Turk, Charles E. Argoff, Robert W Hurley (September 11, 2013). Practical Management of Pain. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1006. ISBN 978-0-323-17080-2.

- ^ Calandre EP, Rico-Villademoros F, Slim M (November 2016). "Alpha2delta ligands, gabapentin, pregabalin and mirogabalin: a review of their clinical pharmacology and therapeutic use". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 16 (11): 1263–1277. doi:10.1080/14737175.2016.1202764. PMID 27345098. S2CID 33200190.

- ^ Uchitel OD, Di Guilmi MN, Urbano FJ, Gonzalez-Inchauspe C (2010). "Acute modulation of calcium currents and synaptic transmission by gabapentinoids". Channels. 4 (6): 490–496. doi:10.4161/chan.4.6.12864. hdl:11336/20897. PMID 21150315.

- ^ Kaye AD, Vadivelu N, Urman RD (2014). Substance Abuse: Inpatient and Outpatient Management for Every Clinician. Springer. p. 324. ISBN 9781493919512. Archived from the original on March 1, 2022. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- ^ "Generic Lyrica Availability". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ "FDA approves first generics of Lyrica". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). September 11, 2019. Archived from the original on June 9, 2020. Retrieved October 27, 2019.

- ^ "Pregabalin ER: FDA-Approved Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved June 19, 2021.

- ^ "Competitive Generic Therapy Approvals". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). June 29, 2023. Archived from the original on June 29, 2023. Retrieved June 29, 2023.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2022". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on August 30, 2024. Retrieved August 30, 2024.

- ^ "Pregabalin Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013 - 2022". ClinCalc. Retrieved August 30, 2024.

- ^ "Is Lyrica a Controlled Substance?". Archived from the original on May 6, 2024. Retrieved May 6, 2024.

- ^ "Is Lyrica a controlled substance / Narcotic?". Archived from the original on February 4, 2024. Retrieved May 6, 2024.

- ^ Preuss CV, Kalava A, King KC (2024). Prescription of Controlled Substances: Benefits and Risks. PMID 30726003.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

GOV.UK-2018was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Controlled Drug Classes". August 12, 2013. Archived from the original on March 28, 2024. Retrieved May 6, 2024.

- ^ "What are Class C Drugs?". October 31, 2022. Archived from the original on May 6, 2024. Retrieved May 6, 2024.

- ^ a b "Control of pregabalin and gabapentin under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971". Archived from the original on February 21, 2024. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ "Pregabalin and gabapentin to be controlled as class C drugs". Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved April 2, 2020.