Back X-straalkristallografie AF دراسة البلورات بالأشعة السينية Arabic Cristalografía de rayos X AST Рентгенова кристалография Bulgarian রঞ্জনরশ্মি কেলাসবিজ্ঞান Bengali/Bangla Rendgenska kristalografija BS Cristal·lografia de raigs X Catalan بلوورناسی تیشکی ئێکس CKB Rentgenová krystalografie Czech Kristallstrukturanalyse German

X-ray crystallography is a way to see the three-dimensional structure of a molecule. The electron cloud of an atom bends the X-rays slightly. This makes a "picture" of the molecule that can be seen on a screen. It can be used for both organic and inorganic molecules. The sample is not destroyed in the process.

Science writer Maggie Koerth (Maggie Koerth's page on regular Wikipedia) provides an analogy:

Imagine that you have captured Wonder Woman's invisible airplane. You can't see it. But you know it's there because when you throw a rubber ball at the space, the ball bounces back to you. If you could throw enough rubber balls, from all different sides, and measure their trajectory and speed as they bounced back, you could probably get a pretty good idea of the shape of the plane.[1]

X-ray crystallography was jointly invented by Sir William Bragg (1862–1942) and his son Sir Lawrence Bragg (1890–1971). They won the Nobel Prize in Physics for 1915. Lawrence Bragg is the youngest to be made a Nobel Laureate. He was the Director of the Cavendish Laboratory, Cambridge University, when the discovery of the structure of DNA was made by James D. Watson , Francis Crick , Maurice Wilkins, and Rosalind Franklin in February 1953.

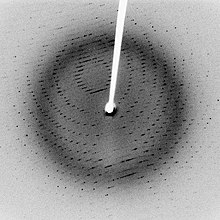

The oldest method of X-ray crystallography is X-ray diffraction (XRD). X-rays are fired at a single crystal and the way they are scattered produces a pattern. These patterns are used to work out the arrangement of atoms inside the crystal.[2]

- ↑ Koerth, Maggie (November 8, 2012). "The Turn of the Screw: James Watson on The Double Helix and his changing view of Rosalind Franklin". Boing Boing.

- ↑ "Introduction to X-ray Diffraction (XRD)". panalytical.com. 2012. Archived from the original on 4 August 2012. Retrieved 6 November 2012.