Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

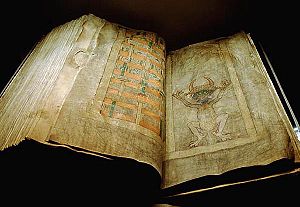

Codex

The codex (pl.: codices /ˈkoʊdɪsiːz/)[1] was the historical ancestor format of the modern book. Technically, the vast majority of modern books use the codex format of a stack of pages bound at one edge, along the side of the text. But the term "codex" is now reserved for older manuscript books, which mostly used sheets of vellum, parchment, or papyrus, rather than paper.[2]

By convention, the term is also used for any Aztec codex (although the earlier examples do not actually use the codex format), Maya codices and other pre-Columbian manuscripts. Library practices have led to many European manuscripts having "codex" as part of their usual name, as with the Codex Gigas, while most do not.

Modern books are divided into paperback (or softback) and those bound with stiff boards, called hardbacks. Elaborate historical bindings are called treasure bindings.[3][4] At least in the Western world, the main alternative to the paged codex format for a long document was the continuous scroll, which was the dominant form of document in the ancient world. Some codices are continuously folded like a concertina, in particular the Maya codices and Aztec codices, which are actually long sheets of paper or animal skin folded into pages. In Japan, concertina-style codices made of paper and called orihon were developed during the Heian period (794–1185).[5]

The ancient Romans developed the form from wax tablets. The gradual replacement of the scroll by the codex has been called the most important advance in book making before the invention of the printing press.[6] The codex transformed the shape of the book itself, and offered a form that has lasted ever since.[7] The spread of the codex is often associated with the rise of Christianity, which early on adopted the format for the Bible.[8] First described in the 1st century of the Common Era, when the Roman poet Martial praised its convenient use, the codex achieved numerical parity with the scroll around 300 CE,[9] and had completely replaced it throughout what was by then a Christianized Greco-Roman world by the 6th century.[10]

- ^ "codex". The Chambers Dictionary (9th ed.). Chambers. 2003. ISBN 0-550-10105-5.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed.: Codex: "a manuscript volume"

- ^ Michelle P. Brown, Understanding Illuminated Manuscripts, revised: A Guide to Technical Terms, 2018, Getty Publications, ISBN 1606065785, 9781606065785 p. 109.

- ^ Lyons 2011, p. 22.

- ^ "CBAA the Association for Book Art Education - A HISTORY OF THE ACCORDION BOOK: PART II // Peter Thomas". www.collegebookart.org. Retrieved 2023-10-26.

- ^ Roberts & Skeat 1983, p. 1

- ^ Lyons 2011, p. 8.

- ^ Roberts & Skeat 1983, pp. 38–67

- ^ "Codex" in the Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, Oxford University Press, New York & Oxford, 1991, p. 473. ISBN 0195046528.

- ^ Roberts & Skeat 1983, p. 75

Previous Page Next Page