Our website is made possible by displaying online advertisements to our visitors.

Please consider supporting us by disabling your ad blocker.

Dosha

| Part of a series on |

| Alternative medicine |

|---|

|

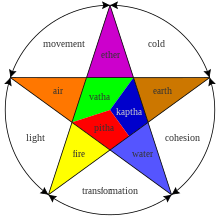

Dosha (Sanskrit: दोषः, IAST: doṣa) is a central term in ayurveda originating from Sanskrit, which can be translated as "that which can cause problems" (literally meaning "fault" or "defect"), and which refers to three categories or types of substances that are believed to be present conceptually in a person's body and mind. These Dosha are assigned specific qualities and functions. These qualities and functions are affected by external and internal stimuli received by the body. Beginning with twentieth-century ayurvedic literature, the "three-dosha theory" (Sanskrit: त्रिदोषोपदेशः, tridoṣa-upadeśaḥ) has described how the quantities and qualities of three fundamental types of substances called wind, bile, and phlegm (Sanskrit: वात, पित्त, कफ; vāta, pitta, kapha) fluctuate in the body according to the seasons, time of day, process of digestion, and several other factors and thereby determine changing conditions of growth, aging, health, and disease.[1][2]

Doshas are considered to shape the physical body according to a natural constitution established at birth, determined by the constitutions of the parents as well as the time of conception and other factors. This natural constitution represents the healthy norm for a balanced state for a particular individual. The particular ratio of the doshas in a person's natural constitution is associated with determining their mind-body type including various physiological and psychological characteristics such as physical appearance, physique, and personality.[3]

The ayurvedic three-dosha theory is often compared to European humorism although it is a distinct system with a separate history. The three-dosha theory has also been compared to astrology and physiognomy in similarly deriving its tenets from ancient philosophy and superstitions. Using them to diagnose or treat disease is considered pseudoscientific.[4][5][6]

- ^ Susruta; Bhishagratna, Kunja Lal (1907–1916). An English translation of the Sushruta samhita, based on original Sanskrit text. Edited and published by Kaviraj Kunja Lal Bhishagratna. With a full and comprehensive introduction, translation of different readings, notes, comparative views, an index, glossary and plates. Gerstein - University of Toronto. Calcutta.

- ^ Wujastyk, Dominik (1998). The Roots of Ayurveda : selections from Sankskrit medical writings. New Delhi: Penguin Books. pp. 4, et passim. ISBN 0-14-043680-4. OCLC 38980695.

- ^ Shilpa, S; Venkatesha Murthy, Cg (2011). "Understanding personality from Ayurvedic perspective for psychological assessment: A case". AYU. 32 (1): 12–19. doi:10.4103/0974-8520.85716. PMC 3215408. PMID 22131752.

- ^ Hall, Harriet (21 November 2019). "Ayurveda: Ancient Superstition, Not Ancient Wisdom". Skeptical Inquirer. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ Raghavan, Shravan (21 November 2019). "What Are The Dangers Of Legitimizing Ayurveda?". StateCraft. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ Kavoussi, Ben (10 September 2009). "The Golden State of Pseudo-Science". Science-Based Medicine. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

Previous Page Next Page